New Delhi: He drove a bright red convertible Mercedes and had a gold Rolex draped around his wrist. He wore shades and a baseball cap, spoke English with an American accent that betrayed perhaps just a hint of his Pakistani origins.

Kamran Faridi, or Abu Muhammad Ameriqi, as some people knew him, was reputed to be a large exporter. Nobody knew exactly what he exported from Turkey. Some people said he dealt in wholesale goods. Others, a little more cynically, thought he was trafficking handicrafts.

He was known as a man with a deep interest in setting up charities for the orphans left behind by the civil war in Syria and often voiced support for the Islamist group al-Nusra, an ally of al-Qaeda. Some people loved him because of his generosity and his willingness to pick up the tab for more or less anything. Others thought he was a bit shady.

No one knew exactly what he was up to, though. Much later, the judge who heard his case said this: “It was perhaps the most difficult sentencing I have ever done.” Judge Kathy Siebel of New York’s Southern District Court, pronounced in December 2020.

The case, she said, was “unlike anything I think most of us have ever seen. The benefit that the defendant gave this country is tremendous and the damage he did didn’t wipe it out completely, but it did a tremendous amount of harm.”

The prison doors shut behind Faridi for seven years. But, he’s going to be emerging from jail this week, having served 72 months. Faridi, you see, was a Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) agent who brought down top Islamic State terrorists, took on Russian gang lords and eventually betrayed his FBI bosses to save a key member of Dawood Ibrahim’s cartel.

Welcome to the Print Explorer. This week, I’m looking at Kamran Faridi’s story because it’s a fantastic and bizarre tale, but it also holds out important lessons. For weeks now, India’s covert services have been facing accusations of working too closely with criminals to battle terrorists and other enemies abroad. The allegation might be true or otherwise, but it raises an important point.

What happens when intelligence services work with criminals as they very often have to? In today’s story, we’re going to discover that the criminal cartels who were cultivated by intelligence services ended up in some important ways, rotting the heart of the institutions and the nation that they were tied to.

Also Read: ‘Ghar mein ghus ke maarengey’ — what India gained from covert war & what are the costs

From slumdog to spy

Kamran started off as just another slumdog in Karachi, hustling on the city’s very, very rough criminal streets. Kamran was born and grew up in Block 3 of Karachi’s Gulshan-e-Iqbal neighbourhood and joined the People’s Student Federation (PSF), the student wing of the Pakistan People’s Party, when he was just a grade 9 student at the Ali Ali School. He started hanging around with older, tough kids at the National College in Karachi and NED University, and grew close to the PSF’s Najib Ahmed, a well-known student leader.

To understand the background, you have to realise that this was a time when student groups in Karachi were quite literally and violently at war with each other. In an interview to one reporter, Faridi said that he started running guns and then got into kidnapping, ransom, carjacking, armed attacks — the gamut of serious crime.

Gulshan-e-Iqbal was dominated by the Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM), which was a group that was at odds with the People’s Party and it soon became difficult for him to operate from home ground. So, Najib, the student leader, helped Faridi shift to Times Square, where he began living with other activists or criminals, call them what you want, living in the apartment complex.

Pretty soon there was trouble with the police, there were warrants out with Faridi and MQM activists were also hunting him down. Not a good place for a young man to be, and Faridi’s parents did what I think any of us would have done if one of our kids was to end up in that situation. They paid off a human trafficker, paid him several lakhs and arranged for Faridi to fly to Sweden, where he applied for political asylum.

Like a lot of young criminals though, Faridi was just unable psychologically to keep himself out of trouble. He soon joined criminal cartels in Sweden, fighting with local Albanian and Bangladeshi criminal gangs. He was arrested a few times by police in Sweden, who unlike police in Pakistan, wouldn’t have encountered him as they say.

But in 1992, they blacklisted him and refused to give him an extension on his visa due to his bad conduct. There was no hope now of his asylum application succeeding. With the help of another illegal immigrant, Faridi went into hiding on an island off the coast of Sweden, where, he told reporters, he was helped out by activists of the environmental organisation Greenpeace.

Local human rights activists arranged a fake passport for him, from where, which he was able to use to travel to Iceland. From Iceland, he finally moved to America and started a new life in that country. Faridi ended up in Atlanta, Georgia in 1994 and ended up buying a gas station in a particularly violent neighbourhood called Bankhead Highway.

We don’t know very much about what Faridi was doing, but he would complain later on that the Atlanta police used to harass and trouble him, trying to get him to work as an informer against Pakistani-Americans running drugs, especially heroin, into the country and somehow came into contact with the FBI during this period.

The FBI recruited him and set him up, presumably impressed by his knowledge of Pakistan and by his criminal background, which if you’re going to be an informant is a very useful thing to have.

The war against IS

What happened next? Well, we know Faridi had a quite incredible career as an FBI operative or FBI agent. In November 2015, Turkish investigators began digging into the Pakistani’s background after the luxury villa he’d rented in Silivri, a seafront suburb west of Istanbul, was raided by counter-terrorism police. Six people were arrested in that raid, including Aine Davis, a British man alleged to have been an Islamic State executioner, part of a group called the Beatles, and subjected at that point to an Interpol red-corner notice.

Now, when the Turkish police began investigating, it was revealed in court that US and British intelligence had told Turkish authorities to let Faridi go, saying he wasn’t linked to the Islamic State. Instead, it was claimed he had some ties to Jabhat al-Nusra, the al-Qaeda linked Syrian group active in Idlib.

What Turkish officials weren’t told is that Kamran Faridi was himself working from the outset with the FBI. He ended up being in touch while posing as this very, very rich businessman, in touch with an Islamic State sympathiser called Al-Walid Khalid Al-Agha. Now, Al-Walid Al-Agha needed a large home. He was a Palestinian in his mid-twenties, who’d grown up in Pakistan before travelling to Turkey and claiming refugee status along with his mother and his nine sisters, hence the need for the large home.

He entered Turkey illegally but managed to get himself some papers. Anyway, he needed a large house for his nine sisters, two wives, and four children. The family, including his mother and sisters, had been living in a rented property in central Istanbul, but neighbours had complained to the police about the noise this enormous family made.

Now, he’d never been able to take out a tenancy agreement in his own name, leave alone the kind of extended family he had because he had no papers or whatever. And the cost, of course, was enormous. But Al-Agha had something that interested Faridi a lot, which were connections. Al-Agha’s family was originally from Gaza. He’d grown up in Pakistan because his father had travelled there in the 1980s to join the Arab Mujahideen fighting against the Soviet Union in Afghanistan.

According to Al-Agha, Faridi agreed to help him out in return for these services to the IslamicJihad and rent a property for about 3,000 Turkish Lira, then about $1,000 a month. He travelled to Istanbul to finalise the paperwork for Al-Agha in August 2015.

The relationship between the two men deepened. Faridi included Al-Agha in some of his mysterious business dealings. The pair was seeking a shared office in Istanbul and drove together to Konya in September 2015 to spend Eid al-Adha there in the very conservative Turkish city.

Now having driven there in that beautiful red Mercedes, Faridi’s connections developed to a point using Al-Agha where he was influential enough to secure permission from al-Nusra to travel into northwestern Syria where he seemed to move around without attracting much suspicion. al-Nusra by way of background had been established in Syria in 2011 with the personal approval of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the self-declared Caliph of the Islamic State.

But by 2013, Baghdadi had split from al-Qaeda and al-Nusra and the Islamic State were engaged in a fierce internecine conflict, competing for the loyalty of jihadists as well as weapons and territory. But al-Nusra and IS fought in this complicated game where they were sometimes allied with the Syrians, sometimes with the Turks for power and territory.

In early 2015, Aini Davis sought the help of Islamic State commanders to cross back into Turkey. A messaging app and phone number, apparently used by Davis, was being monitored and tracked electronically as he travelled across the country, reaching Istanbul on 7 November and stayed, of course, at the house arranged by Faridi, who had also provided those electronic devices that let Western intelligence track Aini Davis.

Big, big coup. They got one of absolutely the top guys in the Islamic State and that wasn’t the only thing Faridi had been up to. In 2018, he travelled to Africa while again running this mysterious cover business where he sought to attract potential terrorists. The Islamic State then was becoming very terrorist.

In 2018, he travelled to Africa with this mysterious business of his, hoping to attract terrorists. As you know, the Islamic State was becoming increasingly powerful both in Somalia and in countries like Angola and Mozambique. Faridi developed relationships with several terrorist affiliates who had played a role in plotting Africa-based attacks.

The FBI also deployed Faridi to Southeast Asia several times in 2016 and again in 2019 to interact with terrorists in that region. And in February 2019, we know Faridi’s assistance helped lead to the arrest of two al-Qaeda operatives in Malaysia.

Faridi was also involved in operations to bring down Russian drug dealers who were trying to traffic heroin and other drugs into the US. He was in every respect a star agent.

The hunt for Dawood

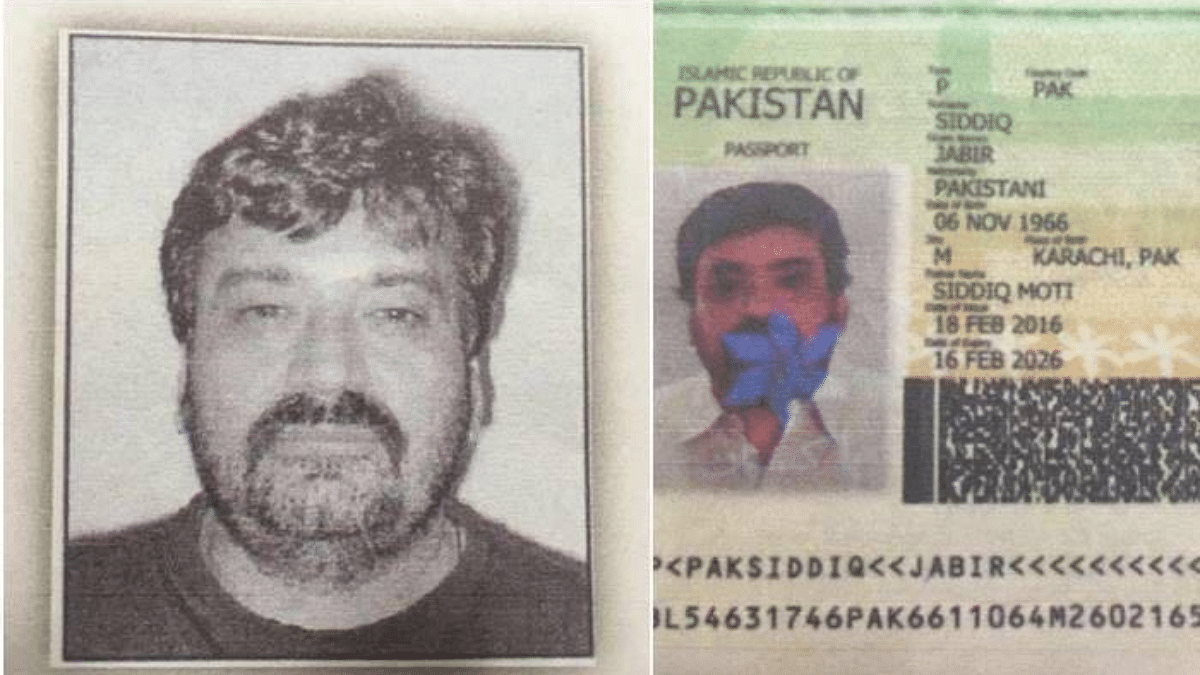

Everything seemed set except for this one operation where things would go horribly wrong. The FBI was looking for Jabir Motiwala who they knew was a key associate of Dawood Ibrahim and the D-Company in Karachi.

Now, as the head of D-Company, Dawood Ibrahim was subject to United Nations Security Council sanctions which describe him as having, and I quote, “used his position as one of the most prominent criminals of the Indian underworld to support al-Qaeda and related groups”.

Dawood Ibrahim was also suspected of running a trafficking empire as well as a terror empire in East Africa and of providing funding to terrorist groups like the Lashkar-e-Taiba. In India, of course, he was most notorious for the 1993 serial bombings in Mumbai which were carried out as retaliation for a communal pogrom against the city’s Muslims which began late in 1992 after the demolition of the Babri Masjid.

Now, as part of this operation against Jabir Motiwala, the FBI relied on three informants who were described in court papers I have been looking at as CS1, CS2 and CS3. And from 2010, many, many years ago, CS1, CS2 and CS3 began holding meetings with Jabir Motiwala.

There were various kinds of deals discussed. One of them involved shipping heroin from Karachi into the US and there were 4 kilograms of heroin involved in that particular run. More importantly, they helped Jabir Motiwala with his critical business which was laundering Dawood Ibrahim’s money.

Now, money is only useful when you can turn drug money which is in cash into things that can be put in the stock exchange or moved abroad, and CS1, CS2, CS3 did that for Jabir Motiwala earning his trust over a period of years. Jabir Motiwala was very reluctant to travel but finally, they succeeded in getting him to come to London where, of course, the FBI was waiting for him.

Now, we don’t know what happened at this stage, but Faridi suddenly broke his relationship with the FBI. There are many stories that have circulated in media accounts, in gossip among the intelligence community about what happened to make things go bad.

One of the stories is that the FBI got fed up with Faridi’s extravagant and faked travel bills and expense statements, and kicked him out. Another story is that Faridi wanted a lot of money because his wife was ill with cancer but the FBI wouldn’t help him out. Another story is simply that Dawood Ibrahim through the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) Directorate made him a financial offer that he couldn’t refuse.

Whatever the truth, Faridi then broke contact with the FBI and tried connecting with Motiwala’s lawyers in London and he told Motiwala’s lawyers that he would say on affidavit that the FBI had asked him to set up Jabir Motiwala and to make false statements about his activities.

So, he said he would say on oath that I was asked to lie in my statements by my bosses and that I refused to lie. What were those lies? The FBI handlers, Faridi claimed, had written a report linking Motiwala to Hafiz Saeed and the Lashkar-e-Taiba, but Faridi had this attack of conscience and wouldn’t do it.

Also Read: How patriots, exiles, disgruntled officers with Japanese help laid ground for Bose to take over INA

Death threats to FBI agents

After his contract was terminated by the FBI in 2020, he actually sent email death threats to his handlers saying that he would sort them out. That of course led to the inevitable results. Faridi flew to the UK in March 2020 with the intention of testifying on behalf of Motiwala but he never made it to the courtroom.

He was detained on arrival at Heathrow airport on the basis of a US arrest warrant and flown straight back without ever facing extradition proceedings since he hadn’t entered the UK.

At Motiwala’s trial though, that was enough because the US Justice Department confronted with this embarrassment that their star witness and agent had now switched to the other side, requested an adjournment in the Motiwala trial and eventually dropped all proceedings.

It didn’t work out for Faridi though because whatever Motiwala or Dawood or the ISI offered him, he was found guilty by a New York court for the threats he’d made against his FBI bosses after losing his job and sentenced to 7 years in prison.

Now believe me, 7 years in an American prison is not a pleasant experience and though last week the judge who heard the case agreed to shorten it to time served, that’s about 6 years, 72 months, he must have had a really miserable time of it and a very unhappy end for a man who brought down a top IS terrorist, who had Al-Qaeda guys arrested in Malaysia, who helped bring down Russian drug lords, ending up in the same jails that the people he’d spied on were rotting in.

The ISI’s heroin empire

But anyway, Faridi is now out and it’s interesting to draw lessons from what he was up to. And for that, we need to look at the wider story of the ISI’s engagement in drugs. In the years before Faridi was shopping around in East Africa, there used to be a business called Magnum Africa Ltd, which protected its privacy like an offshore bank.

Magnum Rice was not a rice trader but it just had a post office box number and the column for the nationality of the directors was left blank. The owner Anwar Muhammad held a Pakistani passport, but that wasn’t his name or his nationality. Munaf Halari was sought by authorities for providing three vehicles which Dawood Ibrahim used in the Mumbai bombings in 1993, in which 257 people were killed.

Following the bombings, the Gujarat police was later to discover, Halari relocated to Kenya with a passport provided by Dawood Ibrahim’s top lieutenant Ibrahim Tiger Memon with the help of the ISI. And there he set up this rice business to act as a front for running heroin from Pakistan, which would then be routed onwards to markets in Europe.

The #GujaratATS early on Monday arrested March 12, 1993 #Mumbai serial blasts absconding accused Munaf Halari Moosa from Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj International Airport, officials said.

Photo: IANS pic.twitter.com/K0NDiysgoY

— IANS (@ians_india) February 10, 2020

Ever since the Afghan Jihad erupted in 1979, the ISI had encouraged mujahideen groups to raise cash by running heroin. Large landowners and drug cartels cooperated with the Mujahideen to ensure smooth movement of the opium crop from Afghanistan to the port of Karachi.

The mujahideen commander Mullah Nasim Akhundzada, the expert Gretchen Peters has written, actually threatened farmers who refused to plant poppy and grow it with castration. Not surprisingly, production of the crop surged.

It just went through the roof. Who wouldn’t grow it confronted with a threat like that? The regime of military ruler General Mohammad Zia-ul-Haq in Pakistan, expert David Winston recorded in a study which was published by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, itself engaged heavily in the drug trade.

Zia, he wrote, I quote, “fostered an ecosystem of government protection of heroin dealers, government officials profiting off the heroin trade and significant political influence of heroin syndicates in the government”.

After the assassination of General Zia in 1988, the ISI continued to tap drug money to pay for its growing operations in Kashmir and elsewhere. And of course, the laundering of these funds and the organisation of these funds was something in which Dawood Ibrahim had a critical responsibility.

Former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif himself, no less, would later allege that he had been approached by then Chief of Army Staff, Lieutenant General Mirza Aslam Beg and the ISI Director General Asad Durrani to authorise large-scale drug deals to fund a series of covert operations for the ISI, for which the government didn’t have the money.

Now, General Durrani has denied these charges. But there’s a mass of independent scholarly and media investigation that shows that the ISI was indeed encouraged in tapping drug lords and the opium trade to enrich itself. The Director of the Central Intelligence Agency’s Afghan operations, Charles Cogan, later told the journalist Loretta Napoleoni that the US basically decided to sacrifice the war on drugs to win the Cold War.

The poppy entrepreneurs

One of those people we know about quite well, which is how we know that these operations continued well into the 2000s. A tall young man who made his way through transit at Frankfurt Airport with 2 kilograms of heroin packed into his handbags.

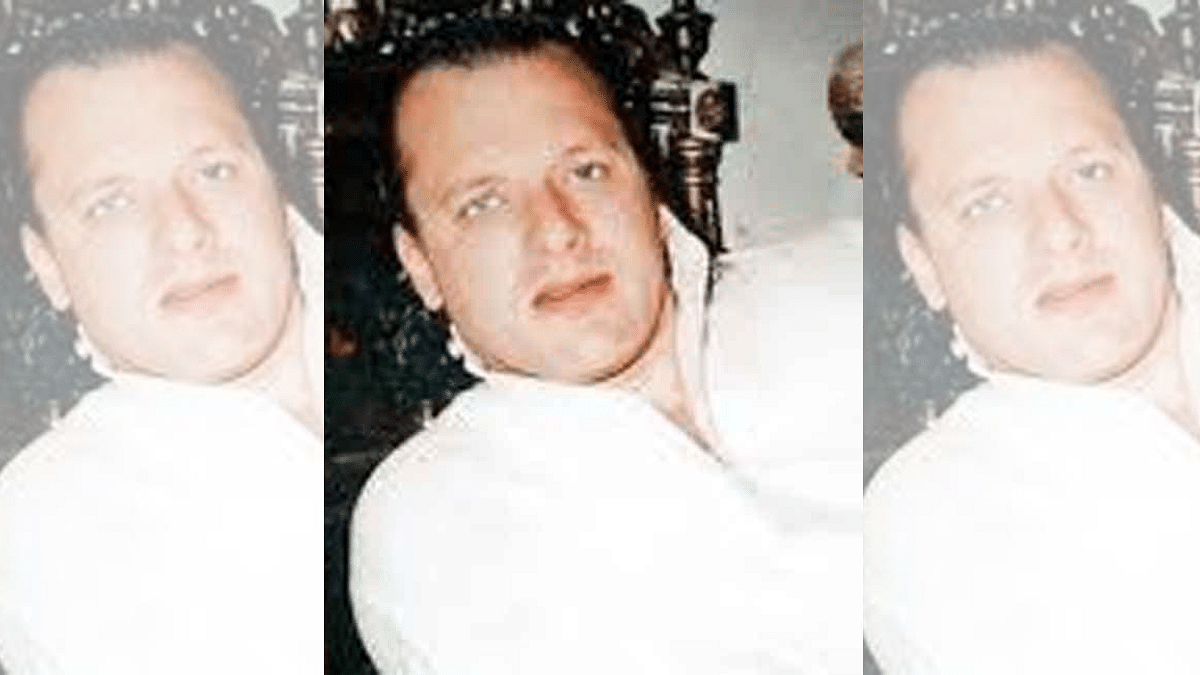

The son of a free-spirited American socialite and a Pakistani broadcaster, one eye blue, the other brown, bearing striking evidence of his mixed heritage, the man was David Coleman Headley.

Now the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) had other ideas and Headley ended up receiving a 4-year prison sentence in 1988. In 1997, the DEA again arrested Headley and this time releasing him only after he agreed to sign up as an informant, just as Faridi had done for the FBI.

This journey would eventually take Headley into the dark world of Pakistan’s jihadists, leading him eventually to 2611 for which he served as the reconnaissance agent with a pretend business in Bombay, just as Faridi had pretend businesses in Turkey and elsewhere.

You see, a new generation of poppy entrepreneurs like Headley was setting up around the world sometimes, some of them genuinely working for the underworld, some of them for intelligence services like the ISI, some for the FBI and other American services. Ethnic Asians with ties of kinship and trade to Karachi often provided the backbone for this expansion, the scholar Simone Haysom has recorded.

The Akasha family in Tahir Sheikh Saeed’s family in Kenya, Ali Khatib Haji Hassan in Tanzania, Ghulam Rasool Moti and Momade Rasool in Mozambique, these little empires of drugs mushroomed around the East African coast. Taliban rule in Afghanistan in its early period saw a dramatic surge in heroin production.

Early on, the trafficking lines through Europe ran north through Iran into eastern Turkey and from Central Asia to Russia. The Dawood cartel pushed south into the Indian Ocean using the services of traffickers like Mir Yaqub Bizenjo, a vocal supporter of former military ruler General Pervez Musharraf, who ended up later being named as the head of one of the four top cartels in the world.

Faced with growing pressure from the US, former Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto occasionally threw Washington a bone, extraditing notorious traffickers like Mohammad Anwar Khattak and Mirza Iqbal Baig.

Islamabad though became mired in drug money. Waris Khan Afridi, appointed Minister for Tribal Affairs by Bhutto, was later arrested for trafficking heroin. Haji Ayub Afridi, once a key figure in Nawaz Sharif’s Islami Jamuri Etihad, was also to come to play a key role in these narcotics networks.

The ISI thus ended up owned by the drug cartels rather than the other way around. And that’s why when Jabir Motiwala was arrested, the ISI reached out to Faridi, desperately trying to have Motiwala released.

What’s the lesson here? Well, like a lot of these spy intrigue stories, there is no neat takeaway. The colourful and fantastic story of Faridi tells us that the dark space between intelligence and criminals is a world where literally enterprise and merit succeeds.

The skilful dissimulator, the talented liar, the fearless criminal can genuinely succeed in making a lot of money. And in this world, betrayal isn’t necessarily seen as a bad thing. Everybody’s working for money, not for their morals.

But when intelligence services have to make these deals, very often they are corrupted. Pakistan’s discovering right now from a report that was released last week that hundreds of officials of the Punjab Police, many of them serving in positions of importance, are actually in the pay of drug traffickers.

In Myanmar, we see that the government has been totally corrupted, the military government has been totally corrupted by drugs. And even in police forces in the US, there’s reputed to be massive corruption there as well as in Mexico and in other countries.

There’s a delicate line to be drawn and as India begins to play the intelligence game more aggressively, it will inevitably run into some of these problems. As we remember the weird and wonderful story of Faridi, we should remember some of the dangers and pitfalls that lie along the way.

(Edited by Tony Rai)

Also Read: Colonial legacy divided Pashtunistan. Chaman protest shows Pashtun nationalism still alive