New Delhi: Even as Field Marshal Sam Manekshaw’s famous Army of Liberation crushed the last pockets of resistance in East Pakistan, India was fighting a bitter war against itself just across the border. Facing a growing tide of protest and killing by Maoist, West Bengal Chief Minister Siddhartha Shankar Ray’s government had unleashed a vigilante army of tens of thousands against communists seeking a revolution.

Large mobs of Congress supporters, often supported by state and central police, hunted down Maoists in the streets of Kosipur, Baranagar and slaughtered rebels in Barasat. In some cases, the leaders of the Maoist were shot dead in Kolkata’s lanes often in full view of dozens of witnesses, historian Manas Roy, an eyewitness to those days, has written.

In others, the police didn’t trouble themselves walking suspects down the roads in the heat; they simply delivered the coup de grâce inside the police station itself.

The scholar Boudhayan Chattopadhyay, an economics professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University and a member of a government-appointed committee to study the naxalite problem, put the numbers of young people killed in those bloody years at 3,000.

Grizzly episodes of wholesale liquidation of teenagers have been reported in the West Bengal press, he wrote in National Herald. Bodies and mass graves continue to be discovered by dogs, jackals and vultures long after the wave had receded.

Fifty years ago the threat of urban Maoist violence, what we today call Urban Naxals, had been stamped out at least in the city of Kolkata. Left revolutionary threat seemed to recede as Prime Minister Indira Gandhi basked in the glow of her two victories, the triumph against Pakistan in the East and against Urban Naxals at home.

The second war we don’t talk very much around, there are no memorials to the dead or for that matter to the victors. Welcome to this episode of ThePrint Explorer. I’m Praveen Swami, and I’m a contributing editor to ThePrint.

So, what is Urban Naxal?

This week as politicians have trampled around the country in the heat and the dust, two events have passed almost completely unnoticed. The Supreme Court held the arrest of the journalist Prabir Purkayastha, alleged to have illegally received funding from the People’s Republic of China, to be illegal.

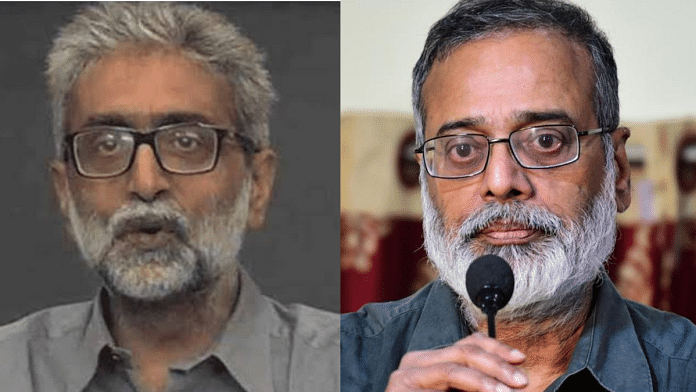

The court also granted bail to Gautam Navlakha, a Left-wing intellectual who’s been a key figure in intellectual circles close to the Maoists. And was accused among other things of participating in the Bhima-Koregaon plot, which prosecutors say involved an attempt to assassinate Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

For our purposes today, the details of these cases aren’t important. You can find a lot of fantastic investigative reporting, as well as some great analysis on ThePrint’s website if you’re interested.

What I want to look at though, is this whole business of Urban Naxals, a term that led both men and many others to jail. Exactly, what is an Urban Naxal? How serious is the Maoist threat in our cities? Is there even a threat? Or, is this one of those moral panics which lead countries into irrational policy responses from time to time, like the infamous Red Scare which paralysed the US in the 1950s?

The issue is complicated even further by the fact that this term Urban Naxals is used very loosely as a term of almost abuse to describe all kinds of people from serious Left-wing revolutionaries who are actually part of the Maoist movement to undergraduate smoking pot on the back lawns of a campus somewhere.

If like me, you’re old enough to have listened to the wonderful Screamin’ Jay Hawkins as an undergraduate, you’ll know urban Maoists have fire pouring from their eyes and smoke billowing from their head. But seriously, let me present to you with two quotes that I think sum up the issue at stake in this debate.

And here’s the first. “I’m convinced that this is one rebellion which will test the resilience of the Indian state as never before precisely because it is a rebellion in which people are fighting to save their land, forests, water and minerals from being grabbed, and they are convinced that they have an alternative vision.” That’s the man who’s just got bail, Gautam Navlakha, Urban Naxal par excellence.

The second is someone who as an undergraduate left the prestigious St. Stephen’s College to go away and become a Maoist, but came back and built a distinguished academic career, the historian Dilip Simeon.

This is what he said. “The Naxalite movement is not a movement of landless peasants and tribals who are seeking to overthrow state power. It’s a project defined as such by those who are neither peasants nor workers, nor tribals, but claim to represent their interests.”

So, what is this debate all about? Finding a definition for who’s an Urban Naxal is surprisingly difficult. You’d think that there would be at least some definition for the threat the country has spent so much time fighting against. But if you look through the entire official record, you won’t find one.

We are aware what was the situation in Congress era. Insecurity, terrorism, bomb blasts vote-bank politics, and lock on the mouth for those into terror activities, Armed forces weren't allowed action. Nowadays Urban Naxals are also trying for entry in Gujarat: PM Modi in Jamnagar pic.twitter.com/A3kpuhtVzX

— DeshGujarat (@DeshGujarat) November 28, 2022

The Home Minister Amit Shah has, of course, used this term. The Prime Minister had cautioned the people of Gujarat to be beware of Urban Naxals, saying they threatened the state’s development.

Except nobody knows how to recognise an Urban Naxal really, except maybe the director Vivek Agnihotri, who made a movie about them.

The Ministry of Home Affairs, in an authoritative statement, says it doesn’t use the term and therefore, doesn’t need a definition. There’s no definition in any criminal case, in any sort of textbook analysis of this phenomenon.

Well, fortunately for us, the Communist Party of India Maoist, whose leaders are serious guys who tended to do very well in college, have left us with some important clues.

In 2007, the CPI Maoist issued a perspective document, as it called it, outlining its plans to expand into urban areas, which is where this whole Urban Naxal debate began. The timing of this document was quite important. As you’ll see from data from the authoritative South Asia Terrorism portal, the Communist Party of India Maoist had successfully revived insurgent violence, which had been ticking up pretty steadily since 2001. And by 2007, the Maoists thought that the time had come to take their struggle forward.

The CPI Maoist perspective document noted that cities were the locus of power of the Indian state. I quote, the cities are the strongholds of the enemy and have a large concentration of enemy forces.

To challenge this, the party called for secret cells to be set up, which would penetrate the ruling establishment. The work is of a very special type, the document says, which requires a high degree of political reliability, skill and patience.

Like jehadis did, the CPI Maoist wanted to set up action teams to operate in urban areas. “Small secret teams of disciplined and trained soldiers of the People’s Guerrilla Army or the People’s Liberation Army, who are permanently based in the cities or towns to hit important selected enemy targets.”

Such targets may be the annihilation of individuals of military importance or sabotage actions like the blowing up of ammunition depots, destroying communication networks, damaging oil installations, etc. That was a pretty serious declaration of intent. The CPI Maoist wanted to carry its insurgency from the countryside to the towns and that’s important for reasons I’ll come to.

Now, if you read that document very, very carefully, you’ll see that it clearly recognised that the Maoist movement’s bases were in rural areas and also that the vast bulk of the party’s attention was on its work in those rural areas. The city would serve as logistic hubs to get arms and ammunition, spare parts, medical supplies, but it anticipated that all the fighting would be out in the countryside.

Also Read: How patriots, exiles, disgruntled officers with Japanese help laid ground for Bose to take over INA

From caste struggles to anti-nuclear protests

Left-wing groups also interjected themselves around this time in a variety of struggles around the country, ranging from the caste struggles of Dalits in Bhima-Koregaon or the anti-nuclear protests at Kudankulam in Tamil Nadu.

The Bhima-Koregaon case is pretty interesting, by the way, in its own right for those of you who aren’t familiar with it. In 2018, Dalit organisations marked 200 years of the Battle of Koregaon. Now, the day had been celebrated by Dalits in Maharashtra because it was an epic battle against a Brahmin king.

The problem was the Dalits who fought in that battle were soldiers of the East India Company, and some people thought it was ‘anti-national’ to be celebrating a defeat of an Indian prince by the East India Company. Of course, Dalits didn’t see it in those terms.

And August 2018, five prominent civil rights activists, Urban Naxals if you want, were arrested under several provisions of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act and accused of having links to the Maoists, conspiring to assassinate the Prime Minister and planning to overthrow the state.

The public prosecutor, Ujwala Pawar, said this, the word Urban Naxal is not defined, but the way they have been using pen drives and gadgets to spread their agenda can be the right definition of the term.

So my reading of that sentence is that she felt that an Urban Naxal was someone who conducted propaganda, not necessarily someone who was actually involved in armed action. There’s nothing to show, though, that these Urban Naxals were especially successful. Perhaps they might have been in the very long term, perhaps not.

We’ll never know because late in 2009, the Union government launched Operation Green Hunt to crush Maoists in Bastar and elsewhere. We’ve discussed that operation in an earlier episode of Explorer, and I might come back to it at some point. But in the years between them and the Bhima-Koregaon incident, the power of Maoist groups had diminished quite significantly.

Now, why did the government panic in the way it did to this spectre of urban penetration by the Maoists? Well, I suspect it’s because the Government of India also knew that its real power lay in cities.

Mahatma Gandhi might have thought of India as a nation of villages, but wealth and power come from India’s urban core. Measured by killings, violence was to peak three years later in 2010, by which time Telangana, Andhra Pradesh, Bengal, Odisha and Maharashtra were all seeing really high and rising levels of violence.

Experts were panicked. You can see from records and conferences and seminars from around that time, that people were talking about Maoist resurgence that could sweep aside the Indian state and rural areas and genuinely worried about the future of the republic.

This had something in my opinion to do with the mystique around the Maoist conception of warfare. In essence, the Chinese leader Mao Zedong who staged a successful revolution in China and of course became its first leader, argued that insurgents should avoid direct conflict with the state until they were in a position to confront its armed forces.

When that stage came, they should surround and choke the cities and thus eventually bring about the downfall of the regime. The Chinese did that pretty successfully. And in the years after 2003, both the governments and the Maoists thought things were headed in that direction.

And then there’s this odd fact. For all the fuss, for all the panic, the Maoists were unable to carry out a single urban operation of any consequence. Unless you count a jailbreak from Jehanabad in 2005 and that was before the Maoist document was written in 2007.

Sure, there were strikes. There were strikes in 2006 in which unions, trade unions, sympathetic to the CPI Maoist were involved, notably at the banks, at public sector banks and at the Hero Honda factory on the periphery of Delhi.

The main forces in these strikes though were unions linked to mainstream parties. The trade unions of both the Congress party and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) were deeply suspicious of liberalisation and privatisation. So, in this business, they were on the same side as the Maoists.

I repeat this just to sum up. Even as they butchered large numbers of police in Bastar and West Bengal and Odisha, India’s Maoists were either unable or unwilling to stage a single operation in a city of significance.

Yes, some Maoist leaders during this period did locate themselves in urban centres like Venkatesh Reddy, who was known as Telugu Deepak. But actually these leaders shifting to cities was fantastic news for counter-terrorism organisations like the police in Andhra Pradesh.

You see, the police had very successfully penetrated the Maoist leadership in previous years. And when these guys moved to cities, they were easy to arrest. It’s a lot easier to pick up someone on the nice streets of a city as the scholar Ajay Sahni has pointed out, than tramping around in a jungle in Bastar looking for them. So, how did Maoists appreciate the military situation as it evolved?

Also Read: Kashmir’s Jamaat-e-Islami wants to rejoin democratic politics. Won’t abandon its toxic project

Revolutionary enough?

There are some very interesting glimpses in an assessment made by the CPI Maoist Central Military Commission in 2012. And here’s what it says. “People are fighting against price rises, unemployment, famine and starvation deaths. Retail traders are fighting against foreign direct investments. Indian Airlines, Air India pilots, bank and Insurance employees, workers and students are fighting against privatisation in their sector.”

So, it’s an opportunity. The interesting thing to me here as an analyst of conflicts is that there’s nothing very revolutionary about any of this. Indian Airlines pilots or bank employees weren’t looking to become the proletarian vanguard and overthrow the Indian state. And this kind of language, you know, the rich are becoming richer, the poorer are becoming poorer. You will hear people say this, you’ll find it written about in newspapers every day of the week.

And by the time all this was written significantly, levels of Maoist violence were actually starting to decline, although very few people noted it at the time.

So the question has to be asked. Are India’s revolutionaries really revolutionary? The historian Kathleen Gough points out that there have been seven major uprisings in the period after independence up until 1977. That is the end of the Emergency.

The first four were conducted by the Communist Party of India before it split into two wings in 1964. Those were Tebhaga in northern Bengal, starting in 1946, just before independence. The Telangana uprising, a peasant uprising, which had to be put down by the military with savage violence against Dalits and Adivasis, a strike of tenants and landless labourers in eastern Thanjavur in Tamil Nadu in 1948, and short strikes followed by attacks on granaries and grain trucks in Kerala in 1946-1948.

According to Gough, the other three uprisings were led by Maoist groups, which began to break away from the Communist Party of India in 1967. There was a peasant struggle involving land claims in 1966, 1971, led by the Andhra Pradesh Revolutionary Communist Committee, an uprising in Naxalbari in West Bengal in 1967.

The annihilation campaign of the Communist Party of India (Maoist-Leninist) against landlords and political moneylenders, landlords, moneylenders and political enemies, which was most intense in Srikakulam in 1969-1970.

Now, what are these uprisings and others of the kind which took place even in the pre-independence period without this Communist label tell us? Well, they tell us this very deep deprivation in rural areas and that there are very sharp conflicts over social inequality in search of a catalyst.

In a previous episode, we looked at rebellions which took place in Bastar and elsewhere in the colonial period, which very often revolved around a shaman or a local princely ruler against colonial authority or against the power of moneylenders and outside influences.

So, this wasn’t a new thing in the Indian landscape. This was very often when Maoist arrived in an area in these peasant rebellions after independence. They were welcomed by local communities because they brought weapons and thus tilted the balance of power between their oppressors and the community, not because the communities were sitting there reading Marx and Mao and had been radicalised by it. In other words, the Maoists weren’t using the villagers, the villagers were using the Maoists.

And in a delightful essay, the scholar Alpa Shah has described Maoists in Jharkhand, for example, as a kind of alcoholic’s anonymous chapter for, you know, back of the beyond communities, heroically trying to do virtuous things and stamp out abuse of local distilled spirits.

She has this wonderful description of what she saw first-hand. “Fifteen men in olive green uniforms, some with sticks and batons in hand, leapt off the bikes and straight towards them. The men started kicking over and hitting aluminium and clay pots, shouting, ‘stop drinking and selling alcohol, long live the MCC, the Maoist Coordination Centre’. In the mayhem that followed, pots cracked and liquor poured onto the ground and villagers started screaming and wailing.”

Well, the mission of civilising Adivasi savages is of course exactly what Hindu nationalists and Christian missionaries have spent decades doing. The Maoists weren’t there as some sort of radical force embracing Adivasis as their own. They were out there doing ‘sudhaar (reform)’.

Even though these movements were crushed without difficulty, what you might call the Maoist impulse was not. The consolidation that led to an expansion of the sphere of revolutionary activity again began in 1970, 1997.

The expert and my colleague, K.N. Reddy, has written various sort of little splinter groups that had disintegrated into Marxist-Leninist groups in the 1970s.

So, you can list among them the Communist Party of India (Maoist-Leninist), the Maoist Unity Center merged with the CPI (Maoist-Leninist) Naxalbari; Revolutionary Communist Centre of India (Maoist) — operating in Punjab — united with the Maoist Communist Center; and the Bihar-based party unity merged with the CPI (Marxist–Leninist) People’s War, which was based in Andhra Pradesh.

So, I don’t know if any of you have ever watched this wonderful Monty Python’s Life of Brian (1971), which has this wonderful series of assassination squads in the Middle East, all naming themselves with a bizarre set of acronyms and letters, this real alphabet soup, and then slaughtering each other over tiny perceived differences.

But that’s what the Maoist movement had become. But in the late 1990s, they all sort of came together, the splits reversed. Reddy has this wonderful analogy of little spots of oil scattered across, sort of, joining each other to re-form a kind of film of a slick over a large area.

So, the Maoist groups through this process of unity and cohesion were able to increase their area of activity and also their cadre and sympathiser base. These potential revolutionaries not only were thus able to bring their ideas into newer areas, but also make determined efforts to reclaim areas where the Maoist movement had been crushed.

This happened in West Bengal, of course, where Naxalbari happened, and Andhra Pradesh. Yet, the Maoists were unable to expand these movements out of this handful of areas. There was no new Maoist insurgency in any state.

This is because, in my view, most Indian peasants had no interest in overthrowing the state. They wanted the state to work better for them. They wanted to be freed of injustice. They wanted to be left alone. But they were not interested in forming some kind of revolutionary military organisation.

And there are two important takeaways from that about why violence actually escalated and grew. The economists Christian Hoelscher and others have made a very interesting point that I quote. ‘Unending violence may actually be the desired equilibrium for all the parties to the conflict’. Does that sound weird that everyone would actually want a state of violence to persist?

Well, think about it. The Maoists made a lot of money for their movement from extorting mining companies operating in Bastar, for example. The companies gained access to land they could mine on when militia was set up in southern Chhattisgarh that forced Adivasis to relocate in camps closer to the road. Funds flowed into development projects, enriching both local elites and the Maoists who extorted money for them.

Everyone loves a war except the people who get killed in them. And perhaps the bureaucracy was happy, too. We talk about schools that didn’t function, government offices that were abandoned. But who would want to be an administrator or a teacher or a doctor working in a back of beyond village? It’s much nicer to be legitimately able to sit in the district headquarters and say, you just can’t go out to help people.

Second, when you go to war, you create powerful vested interests for pursuing the war. The Urban Naxal meme empowered police and opened new avenues for funding local and provincial governments. Hyping the threat made perfect sense. Ajay Sahni has noted that a single incident, not necessarily a violent attack, allowed a district to classify itself as Maoist affected, which is why through this period in the late 2000s, you see a surge in allegedly Left-Wing Extremism (LWE)-affected districts.

The minute you got declared a troubled district, you became eligible for all kinds of central grants, subsidies and money. So who wouldn’t want to be a little bit Maoist affected? Like I said, everyone loves a good war.

Fears of Urban Naxalism have flared up periodically and not just when there’s some feud at JNU, or students are marching against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act or whatever. In 2016 and again in 2017, the derailment of trains in Kanpur, Motihari, and Koneru raised a great deal of fears that Maoist cells were now dynamiting tracks and renewing their offensives on urban areas. The railways’ own investigators though felt that mechanical causes were the likely cause, not bombs. There have been no arrests for terrorism in any of these supposed train blast cases.

There was talk if you go through newspapers from this period of jihadists linking up with Maoists or Indian Maoists linking up with Nepali Maoists. There hasn’t, if you go through the records, been a single case of any such evolution.

You’ll still see periodic reports of Maoist infiltrating trade unions but I’ve always been a little amused by this because the last several years have been a period of retreat for trade unions. They are hardly a consequential force in Indian politics today, unlike at the cusp of liberalisation.

The disproportionate response of police and intelligence organisations to the threat though is at least as dangerous as the threat itself. In the Bhima-Koregaon case, there are credible allegations that evidence was actually manufactured and then planted on the computers of the accused persons. That it’s taken so many years to try the case is scandalous enough that those allegations have not been seriously investigated, undermines the credibility of the Indian state.

And after all, the Indian state like any other nation state ultimately derives its legitimacy from being a vehicle for the delivery of justice and the protection of law. If it doesn’t deliver either of those, then it’s not really that different from the Maoists or any other terrorists.

The threat has also justified extrajudicial violence and executions. There are credible allegations that the Maoists supposedly killed last month in Bastar in a much hailed firefight, were actually unarmed civilians — tendu leaf pickers who were basically passed off as terrorists by the police.

These allegations might be true; these allegations might not be true. But the fact that there is no serious investigation into them underway, is disturbing. So, what of our Urban Naxals? Should we be worried or not?

There’s no doubt that there are many Maoist sympathisers living in our cities, just as there are Hindu nationalists, Congress backers, liberals, authoritarians, communists, and just lackadaisical middle of the roaders, such as myself.

The whole point of a democratic polity though, is that all these different voices and currents learn to coexist. The myth of the Urban Naxals has led to the unravelling of a polity where we are at each other’s throats instead of talking to each other. That could be something India might end up paying a far higher price for than insurgents have ever been able to inflict.

(Edited by Tony Rai)

Also Read: ‘Ghar mein ghus ke maarengey’ — what India gained from covert war & what are the costs