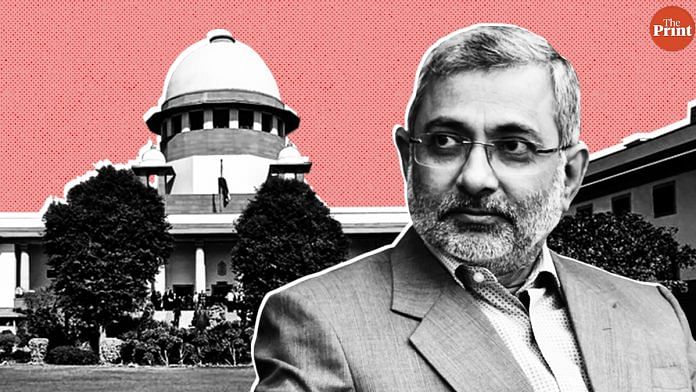

Justice Kurian Joseph, a former Supreme Court judge, has expressed ‘regret’ for his view on the National Judicial Appointments Commission, which he and three other judges struck down in 2015 as unconstitutional. The NJAC was brought in by the Modi government as a replacement for the collegium system for the appointment and transfer of judges of the Supreme Court.

ThePrint asks: Is former SC judge Kurian Joseph right in regretting striking down the NJAC act?

NJAC was an ugly compromise that strengthened the government and political elements

Rajeev Dhavan

Rajeev Dhavan

Senior advocate

Former Justice Kurian Joseph may have changed his mind on the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC), but questions about the alternative remain. The “political” method with consultation of the Chief Justice collapsed after the 1990s. In the last 20 years, the “judicial” collegiums method with consultation of the central government has led to intimidation of the collegiums.

If finance minister Arun Jaitley wants to know who intimidated the judicial collegiums, the answer is it’s his government led by Narendra Modi. The NJAC, brought in through a constitutional amendment, was struck down precisely because it was an ugly compromise strengthening the government and political elements. Little would be left of India’s Constitution if its judicial custodians are selected politically.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government blocked Chief Justice Tirath Singh Thakur, tried to co-opt Chief Justice Jagdish Singh Khehar, and forced Chief Justice Ranjan Gogoi’s collegium decisions. The Supreme Court of India is the most powerful court in the world. But as its power and prestige increases, its standards are falling. The biggest danger is in the saffronisation of the High Court and the Supreme Court, as also attempts to weaken it. We need a new system without the faulty NJAC. In the light of the latest sexual harassment case against the CJI, we also need a judicial accountability complaint system to ensure that complaints against judges are dealt with as they are in other countries.

Remarkable to hear Justice Kurian publicly regret about his decision to agree on striking down NJAC

Prashant Reddy

Prashant Reddy

Senior Fellow, Vidhi Centre For Legal Policy

It is rare to hear retired Indian judges publicly regret judgments they had penned during their tenure. It was thus remarkable to hear Justice Kurian Joseph publicly express regret about his decision to agree, in 2015, with the majority of the Supreme Court bench that struck down the constitutional amendments that had brought in the National Judicial Appointment Commission (NJAC).

The NJAC was meant to replace the opaque collegium system of judicial appointments that has been in place since 1993, when the Supreme Court decided to misappropriate for itself the power to appoint judges. This move to misappropriate the power of appointment has been seriously suspect as it went against the plain text of the Constitution and several decades of convention that gave the executive a prominent say in judicial appointments.

Over the years, the collegium system has lost credibility for a variety of reasons. When Parliament unanimously decided to replace the collegium system by amending the Constitution, it was a reflection of a democratic consensus of the Indian people. The fact that unelected judges decided that “We the People…” had no right to amend our own Constitution is a pointer to the absurdities of the Indian democracy.

Also read: SC collegium’s two new judge picks set to give India its second Dalit chief justice

NJAC is in no way a solution to the executive’s interference in the affairs of judiciary

Bishwajit Bhattacharyya

Bishwajit Bhattacharyya

Senior advocate, Supreme Court and ex-Additional Solicitor General of India

I am respectfully in disagreement with former Justice Kurian Joseph. The National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) order was exemplary because the very concept of NJAC is flawed. The NJAC gives primacy in appointment of judges to the executive, which goes against the very grain of the Indian constitution. Judicial appointment is the very cornerstone of the independence of the judiciary, which is immutable and must not be allowed to be diluted under any circumstances.

The collegium system, on the other hand, has fared quite well in the past and has stood the test of time. It is, of course, true that the collegium needs to protect itself from any and all interference from the executive. Particularly, the appointment of KM Joseph, and how it was stalled for months needlessly, exemplifies how we must actively resist all influence of the executive.

It is since that incident, that there is a growing public perception against the collegium. This is why the collegium needs to thwart any such designs and attempts by the executive, and maintain utmost independence. The executive will always try and interfere; but the collegium in one unanimous voice must speak up against such interference.

That said, the NJAC isn’t in any way a solution to this interference.

Also read: Relaxing income criteria for judges’ post is case of overreach by Supreme Court collegium

NJAC was hastily pushed through but it aligns to Constitution’s vision more closely than the collegium

Suhrith Parthasarathy

Suhrith Parthasarathy

Advocate, Madras High Court

Justice Kurian Joseph, who authored a concurring opinion as part of a 4:1 majority of the Supreme Court bench that struck down the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC), in October 2015, has expressed regret over his judgment. But his disappointment, it appears, stems from the court’s failure to take steps to improve the prevailing collegium system of appointments, to make it more transparent, and to provide to it a machinery that would allow it to operate with greater efficiency.

But any such improvements to the collegium, even if they do fructify, will not remove the flaws inherent in the court’s judgment. In quashing the NJAC, the court proceeded on a belief that primacy of judicial opinion in making appointments to the higher judiciary was a part of the Constitution’s basic structure. What it failed to see was that its view ran counter to the framers’ ideas.

In determining where the power to appoint judges must lie, the Constituent Assembly believed that vesting such authority with the judiciary would flout democratic norms. This is why the Constitution provides for a consultative process involving different authorities. The NJAC may have been hastily pushed through. But its ideas are more closely aligned to the Constitution’s vision than the collegium, whose workings have proved wholly undemocratic.

By Fatima Khan, journalist at ThePrint.

The foremost doctrine of any democracy is Separation of Powers within its three wings with a system of checks and balances. In India, the Executive is accountable to the Legislature and in turn the laws made by the Parliament are interpreted by the Judiciary, which can strike down a law if it views it as unconstitutional. But what are the checks on the Judiciary, excepting the provision of impeachment? This provision is used in rarest of the rare cases. On the other hand, the checks and balances against the Judiciary should be very carefully calibrated so as to preserve its independence. This is a very complex issue and it needs judicious re-examination. We cannot expose our Judiciary to threats of baseless allegations and blackmails by a hostile elements in the civic society. The Judiciary cannot be controlled by any forces.: neither by politicians, the rich and influential, clubs of politically motivated journalists, nor by the dominating and shouting brigade of a section of the Bar and not even by winds of public opinion, which are usually unpredictable and transient. A controlled Judiciary is end of democracy.

National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) was a step in right direction. It had the backing of majority of Indians. It could had been further improved over a period of time. The objections against NJAC weree primarily due to the sharp political divisions in line with pro and anti government mind sets. SC Judges had also fallen victim of propaganda unleashed by a handful of lawyers who are often seen pretending to protect wordly human rights more than poorest of poor Indian’s rights. I had always been for working of government and judiciary together. Otherwise the judiciary in isolation can never improve the justice system in India. So far SC has not shown courage and break the established norms that are doing no good to the future of Judiciary in India.

No doubt NJAC is an attempt of political executive to control independent judiciary at its root by interfering with selection of judges but it is important for the collegium to develop transparency in selection judges by removing any scope for personal and perceptional biases. Next thing is there should be a criteria for poat retirement appointment of judges by Govt. These unregulated lucrative offers from Govt. could be a source of indirect interference of Executive into Judiciary

The judiciary needs to guard its turf from an overbearing executive. Its own infirmities can be redressed by a fearless CJI, assisted by colleagues on the Collegium.

Very correct. But what happens if we one doesn’t find ‘ fearless ‘ CJIs with ‘ good’ colleagues. Then we get the unseemly sight of CJI s declaring themselves innocent with the help of colleagues. Or CJIs accused of corruption, no shortage of accusers, but still no action taken. Simply believing that executive is always bad and judiciary is holier than thou, is no solution. Time for an institutional remedy rather then having to rely on the goodness of fallible humans, for this most important pillar of democracy. Unfortunately the judiciary is unable to clean up it’s own mess a reason for it’s fast eroding credibility. Try filing a case in any Indian court to know what the judiciary means to the common Indian citizen. Right now it seems to be doing everything except that for which it exists, serving the cause of justice.