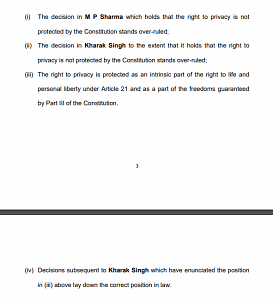

Verdict: In a unanimous verdict, a nine-judge Constitution bench of the Supreme Court Thursday declared that right to privacy is a fundamental right under the Constitution. The court also overruled two previous Constitution bench judgements delivered in 1954 and 1962 – M.P. Sharma vs Satish Chandra and Kharak Singh vs State of Uttar Pradesh, respectively. Both judgements had held that right to privacy is not protected under the Constitution.

Thursday’s ruling also confirms about a dozen rulings of smaller benches that came in the aftermath of Kharak Singh’s case and had held that privacy is a fundamental right are valid.

The nine judges on the bench: Chief Justice of India J.S. Khehar, justices J. Chelameswar, S.A. Bobde, R.K. Agarwal, Rohinton F. Nariman, Abhay Manohar Sapre, D.Y. Chandrachud, Sanjay Kishan Kaul and Abdul Nazeer.

There are six separate opinions. Justice Chandrachud writes for himself, the chief justice and justices Agarwal and Nazeer. Chelameswar, Bobde, Nariman, Sapre and Kaul have written separate concurring opinions.

Context: The question on whether privacy is a fundamental right was referred to a nine-judge bench on 11 August 2015 in a case challenging the legal validity of Aadhaar. The unique identification number was challenged on various grounds including on the ground that Aadhaar violates a citizen’s right to privacy. The government had argued that right to privacy is not a fundamental right. Now that the larger question pf privacy is settled, a smaller bench will decide the fate of Aadhaar.

Questions of law: The 2015 reference to the larger bench had one question – Whether M.P. Sharma and Kharak Singh were correct expressions of the Constitution?

All nine judges held that those cases were wrongly decided.

Additionally, they have answered the question as to whether there exists a fundamental right to privacy? If it does, where does its source lie and what are the contours of that right.

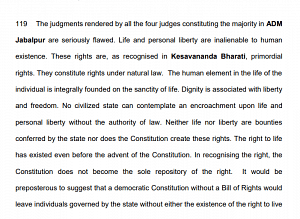

- Justice Chandrachud traces a long list of rulings on right to life and liberty. Notably, in the discordant cases he finds faults with ADM Jabalpur vs Shivkant Shukla, an emergency era case that said that the state can suspend right to life and liberty.

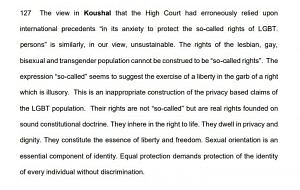

- He also ruled that Suresh Kumar Koushal vs NAZ foundation, the case in which the Supreme Court upheld the law criminalising homosexuality, was incorrectly decided. This ruling is a shot in the arm for LGBT rights.

3. The government had argued that the framers of the Constitution had explicitly left out the right to privacy and hence the right should not be elevated to the status of a fundamental right. Chandrachud says that there cannot be an “originalist” interpretation of the Constitution.

4. Another argument made repeatedly by the government was that privacy is an “elitist concern”. “The poor who depend on Aadhaar for government’s benefits do not care about sharing biometrics,” the attorney general had argued. On this, the ruling says that the “conditions necessary for realising or fulfilling socio-economic rights do not postulate the subversion of political freedom.”

Justice Chelameswar’s ruling:

- Chelameswar, while addressing the government’s argument that there cannot be a specific right to privacy since the framers of the Constitution did not envisage it, says that there are many other rights that are not to be found anywhere in the text of the Constitution.

- Borrowing from American scholar Gary Bostwick, he defines privacy to include three main aspects.

3. Further, giving examples of what right to privacy would mean, he outlines what states cannot do.

Justice Nariman’s ruling refers to three dissenting opinions by justices Fazl Ali, Subba Rao and Khanna. The cases in which they have dissented: A.K. Gopalan vs State of Madras, Kharak Singh vs State of Uttar Pradesh and ADM Jabalpur vs Shivkant Shukla have become the law on fundamental rights.

- The Unique Identification Authority of India had argued that privacy need not be a fundamental right since the legislation on Aadhaar, among other statutes, sufficiently take care of privacy concerns. Nariman disputes this claim.

2. Advocate Gopal Sankarnarayanan, appearing for a non-profit, had pointed out that if right to privacy is elevated to the status of a fundamental right, that cannot be waived, it could create complications. Nariman suggests a way out.

Impact: The historic ruling will have implications on many cases that are pending. Instantly, the cases challenging the two-finger rape test, government orders banning pornography, decriminalisation of homosexuality will be immediate fallouts, apart from the case challenging Aadhaar.

Key References:

- Kharak Singh vs State of Uttar Pradesh – (1964) 1 SCR 332

- M.P. Sharma vs Satish Chandra, District Magistrate, Delhi – (1954) SCR 1077

- A.K. Gopalan vs State of Madras – AIR 1950 SC 27

- ADM Jabalpur vs Shivakant Shukla – (1976) 2 SCC 521