“The alternative was war.”

Former Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s public statements and private letters in the first quarter of 1950 had various versions of this sentence. He was trying to figure out a solution to the communal violence in Bengal, which had led to a large-scale exodus of Hindus from East Bengal to West Bengal, Tripura, and Assam, and of Muslims from West Bengal to East.

It was either war or an exchange of population—and Nehru wanted neither. So he devised a third option: A pact with his Pakistani counterpart Liaquat Ali Khan, which was signed on 8 April 1950 and came to be known as the Nehru-Liaquat pact or the Delhi pact.

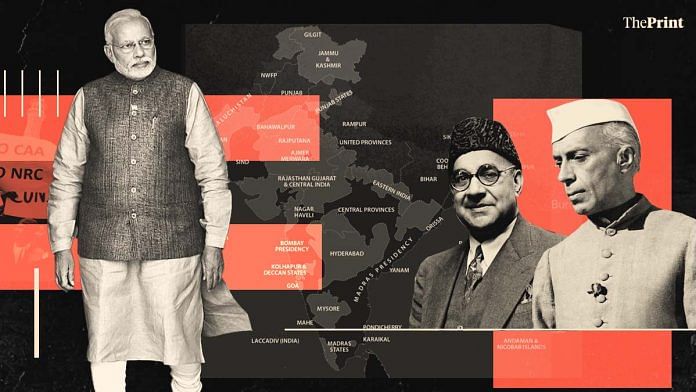

“The alternative was war,” Nehru again wrote two days later to Syama Prasad Mookerjee who resigned in opposition to the agreement. Mookerjee later went on to establish the Bharatiya Jan Sangh (BJS), the predecessor of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). The ‘failure’ of this pact has now undergirded the current BJP government’s controversial Citizenship (Amendment) Act 2019.

The law aims to benefit Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi, or Christian undocumented immigrants from Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan who entered India before 31 December 2014 and seek citizenship in the country. While making his case for the Citizenship (Amendment) Bill back in 2019, home minister Amit Shah repeatedly spoke of this pact. He pointed out that under the Nehru-Liaquat Pact, both countries agreed that they would look after their minorities. The pact had “failed”, he said, and there would have been no need to bring this Bill “had the spirit of the pact been followed by Pakistan”.

Hours after his speech, the contentious Bill was passed in the Lok Sabha—at the stroke of midnight on 9 December 2019. The midnight time stamp has been a significant marker of change in Indian history as well as mythology—from the birth of Krishna to the declaration of the Emergency in 1975. This time, it signified India’s characterisation as the proverbial promised land for persecuted minorities from these three neighbouring countries. The Narendra Modi government has now notified the rules of the Citizenship (Amendment) Act 2019, paving the way for the implementation of the controversial law.

Nehru’s name routinely comes up when the BJP justifies this law. However, this time, PM Modi has, in fact, claimed to be doing exactly what Nehru wanted to do—protecting the minorities.

“Pandit Nehru himself was in favour of protecting minorities in Pakistan, I want to ask Congress, was Pandit Nehru communal? Did he want a Hindu Rashtra?” he asked in February 2020, questioning the Congress party’s stand on CAA.

Suhas Chakma, director of Delhi-based think-tank Rights & Risks Analysis Group, finds weight in this argument. “The treatment of Hindus and Muslims as separate categories is actually a legacy of Nehru and Congress, and BJP is basically implementing that policy,” he told ThePrint.

However, there seems to be a vital difference between the Nehru government and the Modi government.

“The reason that the 1950s were different from today is that the 1950s were a time when people looked forward after Partition, whereas now, with the talk about CAA, it’s a way of re-litigating the rights and wrongs of Partition,” says Pallavi Raghavan, author of Animosity at Bar: An Alternative History of the India-Pakistan Relationship, 1947-1952.

Also read: 1967 was the year politics changed. Modi wants to go back to the simpler times before that

‘His word goes a long way’

The pact almost immediately came in for criticism after it was passed in April 1950. Two prominent Hindu Mahasabha members of the Nehru cabinet, Mookerjee and KC Neogy, resigned.

Back in Pakistan, the first law and labour minister Jogendra Nath Mandal resigned in October 1950 and returned to India, leaving behind the scores of Dalit Hindus who he had assured of Dalit-Hindu and Muslim unity back in East Pakistan.

In his resignation letter, Mandal called out the East Bengal government and the Muslim League leaders for lacking an “earnest desire” to implement the pact.

However, Raghavan explains that at the heart of the Nehru-Liaquat pact was the principle of reciprocal responsibility, making the governments of India and Pakistan answerable to each other on the question of refugees and the welfare of their minority populations.

She pointed out that the Nehru-Liaquat Pact also reflected an understanding that that question of minority rights was broader than simply a matter of the breakdown of law and order during episodes of rioting. She explained that the text of the pact contained a detailed and comprehensive set of assurances designed to safeguard minority communities from daily challenges, including provisions against discrimination in employment, educational institutions, preservation of cultural institutions as well as specifically worded safeguards of rights over property.

In contrast, now, the way in which minority protection is visualised is based on a narrower set of parameters usually defined only by violence.

Nehru himself had two parameters on which he wanted to test the success of the agreement. At a press conference two days after the pact was signed, he told reporters that the two most important criteria were the preservation of order and protection of the people and a decrease in the exodus.

According to Raghavan, the pact was a “partial success”. “What the pact did was staunch the flow of refugees coming in from East Pakistan and avoid a war with Pakistan. It was also an answer to chief ministers who felt that the central government was weak because it was not taking strong enough action against Pakistan,” she says.

Nehru’s faith in the implementation of the pact also drew from Khan’s standing in Pakistan. “His position, I believe, in Pakistan is such that his word goes a long way,” he told reporters at the same press conference in April 1950.

However, Khan was assassinated in October 1951, and with him died the dreams of political stability in India’s neighbouring country.

“The pact led to failure because of Pakistan’s political instability and the increased belief that Pakistan was being created for Muslims,” says author and political analyst Rasheed Kidwai. He pointed out that the pact provided a strong base for the protection of minorities. “But implementation requires sincerity from political masters, and that was lacking on Pakistan’s side.”

Also read: Duties, duties, duties. Modi is going back to the Indira Gandhi Emergency era

‘Orgy of murder’

In the few years before and several years after Partition, the tinderbox of India and Pakistan relations kept flaring up with every spark, which were aplenty.

While the origin of the 1950 crisis is hotly contested among historians, it appears to have originated in the Khulna district, as per Nehru’s address in Parliament in February 1950, of East Pakistan in December 1949. Hindus began trickling down from Khulna to West Bengal, bringing with them gruesome stories of violence and harassment, unsettling West Bengal with anti-Muslim sentiments.

It soon became the severest trial that the country had undergone in the two and a half years since Independence and Partition-driven bloodshed in Punjab. Nehru sprung into action right away.

In a statement to the press on 10 February, Nehru declared: “On no account must we fall a prey to communal passion and retaliation.” However, across the border, his counterpart Khan refuted India’s account of events in a statement in Dawn on 13 February and claimed that the Khulna incident was non-communal in character, a version that Nehru found to be “distorted ”.

Over the next two months, several telegrams were exchanged between the two governments on what should be done next, betraying an anxiety to find a solution to avert the crisis. Nehru said that conditions have arisen in East Bengal, which make it exceedingly difficult for non-Muslims to live there with security, leading to large-scale migration between the two countries. Feeling “terribly sorry for what took place in Calcutta”, Nehru was clear that it could not be compared with the violence in East Bengal.

Nehru wanted two joint fact-finding commissions—one for each Bengali province—for a “fairly quick overall survey”. He also proposed that both he and Khan should visit the affected areas on both sides together. Khan rejected both his proposals and instead pushed for a declaration from both governments that they discouraged migrations across the provinces and that minorities would be rehabilitated in their homes.

In the meantime, the violence in East and West Bengal continued to escalate, leading to large-scale migration of Hindus to Indian states. On 5 March 1950, Nehru told former Governor-General of India Louis Mountbatten that in the last three weeks, about 60,000 Hindus had migrated from East Bengal to West, and about 15,000 to 20,000 Muslims had travelled from West Bengal and Assam to East Bengal.

The East Bengal press was, meanwhile, fanning the flames with banner headlines reading: “Orgy of murder, arson and loot” and “Inhuman oppression of the peace-loving Muslims”. Bengali and Urdu leaflets called for avenging the bloodshed in Calcutta.

Also read: Nehru’s Hindu Code Bill vs Modi’s UCC— same script, same drama, different Indias

‘Prepared for martyrdom’

While Nehru’s communication with his “dear Nawabzada” was failing to find a solution agreeable to both governments, everybody else in India had their own ideas of what the correct path was. A few Hindu and Sikh communal organisations spoke about “forcibly uniting the country again”. The clamour for stricter action was getting louder, even within the Gandhian wing of the Congress. Socialist JB Kripalani openly wrote: “Those who feel that they have right on their side must be prepared for war or martyrdom, but never for cowardly submission.”

Even Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel reportedly invited some party MPs for a meeting and allegedly criticised the government policy regarding Bengal and foreign affairs—a development that left Nehru “deeply perturbed”. He could feel the walls closing in.

By March 1950, the mobilisation of the Army had begun, in what has been called the largest movement of Indian forces since Independence, as Raghavan’s book. With Nehru wanting neither war nor population exchange, the move was a carefully orchestrated diplomatic dance.

As Srinath Raghavan writes in his book, War and Peace in Modern India, Nehru intended to convey the threat of force to Pakistan but was careful to minimise the actual possibility of war, writing to chief ministers that it was important to desist from “talking and encouraging war sentiment”. However, the news of troop deployment soon reached Khan, who wrote to Nehru on 6 March, mentioning reports of troop carrier concentrations on the borders of East Bengal. The Pakistan government also stepped up its diplomatic efforts, writing to the United States ambassador in Pakistan to persuade India to remove the military threat and sending similar messages to foreign ministers in England and Canada.

Months of back and forth came to a close when Khan finally came down to Delhi on 2 April 1950 and the pact was signed on 8 April, with the two governments agreeing to give their minorities “complete equality of citizenship, irrespective of religion”. It gave them a full sense of security, culture, property and personal honour and freedom of occupation, speech and worship.

With this came the emphasis by both governments that “the allegiance and loyalty of the minorities is to the State of which they are citizens, and that it is to the Government of their own State that they should look for the redress of their grievances.”

Carrying forth Nehru’s legacy

Partition broke not just India’s integrity but also families like Mohd Din Chatriwala’s, a rich Delhi merchant. His sons decided to leave Delhi and begin a new life in Pakistan. So he went back and forth between Delhi and Karachi after Partition to settle his sons in. However, when he returned to Delhi in 1948 after one such trip, he found that he had been declared an evacuee and all his properties had been taken over by the custodian of evacuee property under the Administration of Evacuee Property Act 1950. His properties were finally released after he made an appeal to the government for a no-objection certificate.

This was the immediate challenge of Partition—ensuring the security and rehabilitation of people moving across the border. At the time, the abandoned properties of Muslim migrants described as evacuees were available for the ‘refugee’ Hindus from Pakistan. However, records show that several Muslims at the time moved to camps to find safety among fellow Muslims in India and some left for Pakistan with the intention of returning after the situation had calmed down.

Chakma points out that the Nehru government treated fleeing Hindus and Sikhs from Pakistan as refugees, but the Muslims who wished to return to India were called evacuees under the Administration of Evacuee Property Act 1950 and Displaced Persons (Compensation & Rehabilitation) Act 1954.

He, therefore, feels that the CAA takes forward Nehru’s perspective on refugees right from Partition.

Chakma adds that the pact itself was a failure. However, his reasons are different from the BJP’s.

“It was a complete failure because the pact should have led to some kind of development of a refugee law and legal process in India,” he asserts, recounting the various instances in the past century that saw the movement of populations and continued influx of refugees in India.

Pakistan’s ‘neglect’

The ghost of the pact continued to haunt political leadership in India over the next few decades, resurging in debates every time India-Pakistan relations were strained.

In April 1964, socialist leader HV Kamath asked the government if it was going to take up the issue of “barbarous persecution of minorities in East Pakistan verging on genocide” with the United Nations General Assembly. The response was a curt ‘no’. The Nehru government was still hopeful of discussing this issue “fruitfully” at a scheduled meeting of the home ministers of the two countries—which would go to war a year later instead.

Two years and a war later, BJS leader Niranjan Varma brought up the Nehru-Liaquat Pact in Parliament once again in August 1966. In response, External Affairs Minister Sardar Swaran Singh claimed that while India has continuously safeguarded the rights and security of minorities, “Pakistan has persistently contravened the provisions of the Pact through consistent neglect and harassment of the members of the minority community”.

The instances of such violations, he said, started to come to notice almost immediately after the inception of the pact. He claimed that at that time, this matter was taken up “very vigorously” with the Pakistan government. His response ended with an apparent attempt to placate the concerns around the well-being of minorities.

He said that of late, cases of undue harassment of minorities in East Pakistan “have not been many”.

‘Akhand Bharat’

CAA is now being justified by the ‘failure’ of this pact, invoking arguments very similar to those being harped soon after Partition.

Defending CAA, Amit Shah said last month: “Those who were a part of Akhand Bharat and who faced religious persecution, I believe that giving them refuge is our moral responsibility.” This isn’t a new argument for the Hindu Right.

In fact, back in February 1950, grappling with the East and West Bengal violence, Nehru was certain that the Hindu Mahasabha’s talk of putting an end to Partition was “foolish in the extreme”.

“There must be no thought of putting an end of Partition and having what is called Akhand Bharat,” he wrote.

As public debate on the CAA continues, the Supreme Court is also set to consider the 200-odd petitions challenging the law.

However, former Supreme Court judge Justice MB Lokur insists that the CAA must not be looked at from a narrow perspective and must be considered along with the National Register of Citizens (NRC) and the National Population Register (NPR).

“If the entire package is considered, the CAA will be struck down,” he told ThePrint, while adding that even if it is considered as a standalone legislation, it is “constitutionally infirm and discriminatory”.

The legal arguments against the CAA have traditionally rested on the grounds that it violates the right to equality under Article 14 of the Constitution as it provides differential treatment to illegal migrants on the basis of their country of origin, religion, and date of entry into India.

While petitions in the Supreme Court have been pending, the law itself is ready for implementation through the rules that were notified last month—over four years after the law was passed. The rules for any law have to be framed within six months of presidential assent, or the government has to seek an extension from the committees on subordinate legislation in the Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha.

In this case, the government asked for nine extensions.

Who is persecuted?

CAA and the rules under it come as a respite for migrants who might not have any valid travel documents as mandated by the Citizenship Act 1955.

Under the CAA rules, immigrants from the three countries mentioned in the law only have to prove the country of their origin, their religion, date of entry into India, and the knowledge of an Indian language to apply for citizenship.

Kidwai emphasises on the “political intent” of laws across the world.

If the intent is to help out religiously persecuted minorities in these three countries, it is welcoming. But if it is to reopen those wounds of 1947, when nobody was in charge and everybody was at fault, then I’m not sure whether it is beneficial for society.

He laments the fact that there is nobody now to explain the nuances of Partition and how it had become inevitable.

“Now, anybody who is interested in knowing the basics of CAA goes back to Partition. This is where the otherisation takes place…rather than seeing it as a historical wrong,” he says.

Apart from the historical context of Partition, the 2019 law itself seems to have several practical difficulties.

Chakma says that under a refugee policy, people can be given refuge on the basis of individual persecution that they face.

“In the current situation in which they are giving en masse citizenship to the people who have fled from these countries, the question arises that if a Hindu becomes a minister or advisor to the government of Bangladesh, is that person facing persecution there?” he asked.

He acknowledges that persecution is attributable to a community, but at the same time asserts that vulnerability has to be decided on individual claims.

This is where he also circles back to his claim that CAA is based on Nehru’s legacy of treatment of refugees.

“India always treated people, who had come from the other side of the border, based on their religion,” he says.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)