Prime Minister Modi’s words rang loud and clear as he addressed a gathering over video call: the next 25 years of Independence will be India’s Kartavya Kaal — the Era of Duty.

It was a very Kennedy-esque ask of the nation. It’s odd that the duty reminder from Modi keeps coming up at a time when all the din is about the shrinking of civil rights in India.

Modi was speaking at the inauguration of a convention centre in Puttaparthi, Andhra Pradesh in July, but his government has been signalling this move for years. His speeches are rife with references to how rights are embedded in duties. During his 2023 Independence Day speech, Modi emphasised “duty” four times in a single breath. “It is the duty of all of us, the duty of every citizen, and this era — Amrit Kaal is Kartavya Kaal — an era of duty,” he declared. He also brought duties up during his last speech in the famed Central Hall of the Old Parliament building: “The Central Hall inspires us to fulfill our duties,” he said, paying homage. “It is where our Constitution took shape.”

The emphasis on duties over rights underscores his vision for India. Even the national capital’s iconic Rajpath, the boulevard leading up to the Rashtrapati Bhavan, has been renamed Kartavya Path: the path of duty.

But this kernel was planted in the Indian psyche by former prime minister Indira Gandhi during the Emergency, a time when the State was accused of overriding citizens’ rights.

The 42nd Amendment, introduced in 1976, is mostly remembered for amending the Preamble’s description of India from a “sovereign democratic republic” to a “sovereign, socialist, secular democratic republic.” What’s lesser known is that it also amended dozens of other articles, and added 14 new ones — including perhaps its most prescient addition, that of the fundamental duties.

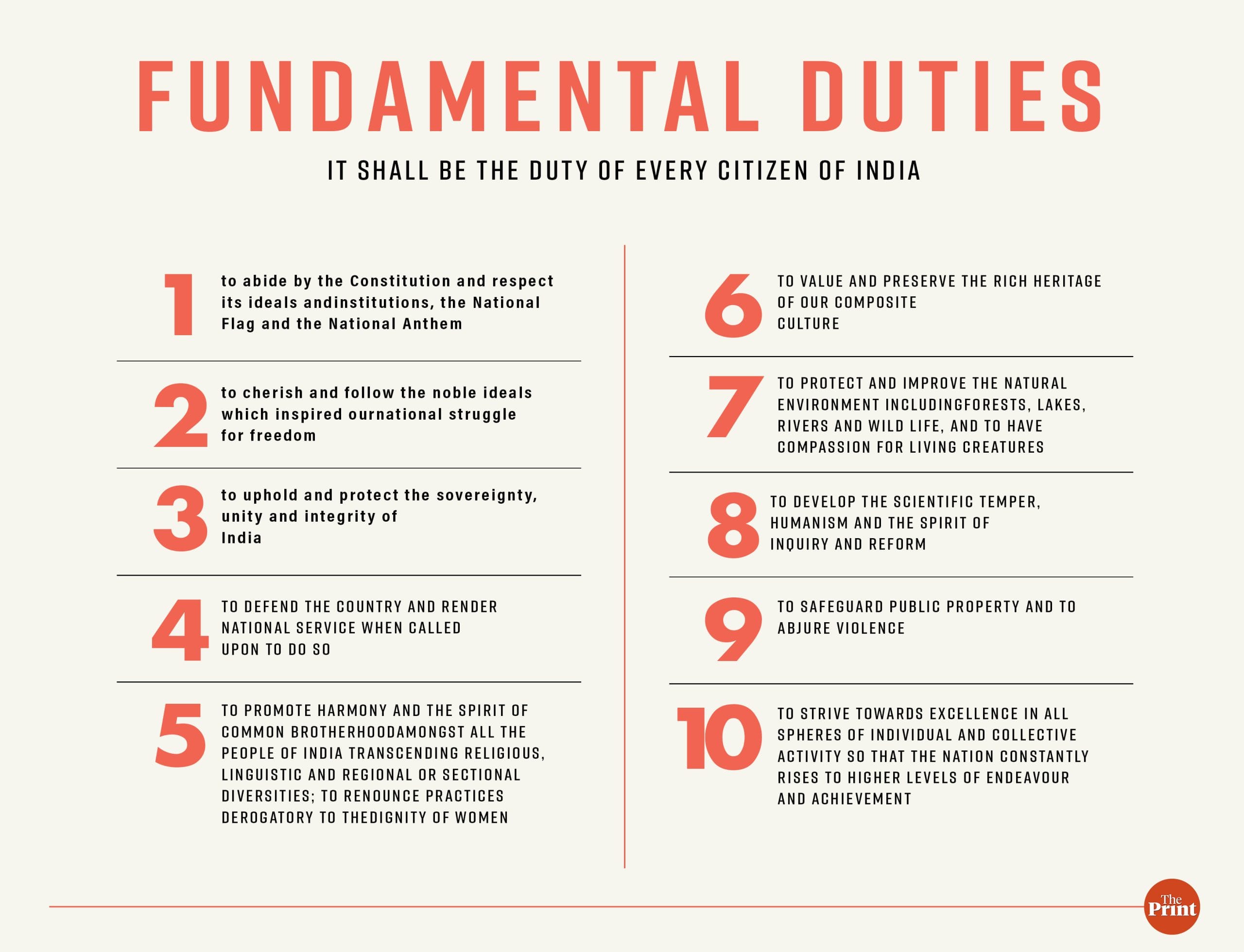

Fundamental duties are the moral obligations that all citizens of India have towards the State. The 42nd Amendment listed 10 such duties, an eleventh was introduced in 2002. They are not enforceable by law, and therein lies the rub — it is up to the individual in question to not just perform their duty to the State, but also define the scope of their duties.

The Emergency ended, Indira Gandhi lost the election, and a new government came to power in 1977, and most of the 42nd Amendment, was undone by the 44th Amendment and the subsequent Minerva Mills judgment, but the duties have stayed enshrined in the Constitution.

And subsequent governments — like the Modi government — have doubled down on them. Some, like legal scholar Upendra Baxi, argue that the fundamental duties are now part of the basic structure of the Constitution.

Now, as the public debate on the basic structure of the Indian Constitution has once again popped up after former Chief Justice of India Ranjan Gogoi’s maiden speech in the Rajya Sabha – duties are back at the centre of the table.

The recent obsession with fundamental duties is a paradigm shift, which is what makes the current dispensation so similar to the Emergency-era. And its purpose was to “erect a mask over violations of citizen’s rights,” according to Vineeth Krishna, lead associate editor at the Center for Law and Policy Research.

That was the year when the erstwhile Human Resources Development Ministry sent a letter to educational institutions on how to celebrate Constitution Day — five out of nine directives emphasised Fundamental Duties. There was no mention of rights.

“The government was pushing for Fundamental Duties forcefully, the subtext being that Fundamental Rights weren’t that important. It was a dangerous idea — coercing powerless citizens to perform duties under a State that enjoyed ad hoc powers,” Krishna told ThePrint. “In that respect, Indira Gandhi and Modi are quite similar.”

Also Read: ‘Air India ki flight mat lo’ — how Canadian neglect led up to Kanishka bombing 38 yrs ago

Modi government’s view on duties

Long before Indira Gandhi and the Emergency, it was another Gandhi — the Nation’s Father, Mahatma Gandhi — who gave us a template for citizenhood. And this template hinged on duties, and not rights.

In fact, Gandhi saw no distinction between rights and duties — and the latter always came first. “Right is duty well performed,” he wrote in Hind Swaraj. Moreover, according to the founding figure, an Indian citizen could give up rights — but duties, being sacrosanct, could never be bypassed. “Violence becomes imperative when an attempt is made to assert rights without any reference to duties,” Gandhi said to anthropologist Nirmal Kumar Bose in an interview in 1934.

Modi has echoed Gandhi’s thoughts on multiple occasions. In a 2019 op-ed in The New York Times, the PM quoted Gandhi as saying “the true source of rights is duty”. He even referenced Gandhi in a joint session of Parliament the same year, saying “Gandhi Ji said that we can only expect all rights when we perform our duties to perfection. Thus, according to the Father of the Nation, duties and rights were directly linked.”

The 42nd Amendment was introduced to legitimise a political executive during the Emergency according to Baxi, noting that the duties have not been repealed by any government that followed. The fundamental duties have stood the test of time, and are now an unalterable part of India’s legal fabric, part of the Constitution’s basic structure. It is only when certain rights are guaranteed that duties can be performed, and vice versa.

Violence becomes imperative when an attempt is made to assert rights without any reference to duties

– MK Gandhi in 1934

It was this understanding that had been shaped into material form in 1976. So it isn’t unsurprising that it has come back now in the 21st century — marking the Kartavya Kaal.

Who is a dutiful Indian citizen?

Nor is it surprising that duties have found their way into RSS and BJP’s discourse. The concept of duties to the State has been around since before the Constitution.

“The idea of dharma is duty,” said Vinay Sahasrabuddhe, president of the Indian Council for Cultural Relations. “There is a fundamental difference between “Indian thinking” and the thinking of other countries — especially Leftist ideology-driven countries — that have disproportionately emphasised rights over duties.”

Pointing to the Indian family unit and structure as an inherent way of learning about democratic spirit, Sahasrabuddhe said growing up in an Indian family teaches the young about the importance of individualism — and not at the cost of collectivism. And it has been around since time immemorial, deeply embedded in the traditions of India.

“The discharge of one’s duties is ensuring the protection of the rights of others. Our Constitution has amply clarified the duties one has towards the country,” he added.

But even before the Constitution, there was a firm discourse on the duties one owed the State, dating back to texts like the Bhagavad Gita and concepts like dharma. It took on a new dimension when it came to nation-building.

Hindutva ideologue, VD Savarkar, in a famous speech delivered in Karnavati in 1937, stated that there can be “no distinction nor conflict in the least between our communal and national duties, as the best interests of the Hindudom are simply identified with the best interests of Hindustan as a whole.” Savarkar continued to say that “the truer a Hindu is to himself as a Hindu,” the truer he can be as a nationalist. The way to do this, he elaborated, was in the discharge of duties and obligations to the Indian State as a whole.

While most historians don’t see Savarkar as a national figure, he has since been hailed as a man who “spent life on the path of duty,” by PM Modi. During his Independence Day speech in 2022, Modi listed Savarkar alongside Mahatma Gandhi, Subhas Chandra Bose, and BR Ambedkar as men who discharged their duties to the Indian State. In Savarkar’s biography, he is described as a man who despised those who “shirked duty for fear of consequences.”

To him — and to other Right-wing ideologues like MS Golwalkar investing in building a new nation — “duty” was a fundamental virtue to have. But Golwalkar’s Bunch of Thoughts and speeches by Savarkar don’t elaborate on what these duties entail. Until the 42nd Amendment, it was very much an amorphous idea built on morality.

Also Read: When Indira Gandhi nationalised foodgrain and failed — a disaster and a cautionary tale

A back and forth

Even if it was introduced in an arguably undemocratic way, the 42nd Amendment was by far the most comprehensive amendment to the Constitution. It amended the Preamble and 40 Articles, the Seventh Schedule and added 14 new Articles to the Constitution.

In November 1976, law minister HR Gokhale termed the introduction of the 42nd Amendment the “finest hour in the post-Independence era” and Congress MP Liladhar Kotoki called it the “day of deliverance”.

What underscored the amendment was the emphasis on citizens’ fundamental duties. An overwhelming emphasis on ‘common’ good — and a feverish nationalist sentiment — rang through Parliament.

MP Dinesh Chandra Goswami quoted Nehru saying, “We who have been fighting for our rights and have finally achieved them are apt to forget that a right by itself is incomplete and, in fact, cannot last long if the obligations which accompany that right are forgotten by the nation or by a greater part of it.”

But all the enthusiasm, which the Opposition called the “erosion of fundamental rights”, had come after many tantrums, turmoil, and tumult. While the judiciary expressed its anxieties, Gokhale outrightly claimed: “No confrontation with Parliament!”

For Congress MPs, the 42nd Amendment was a symbol of the supremacy of Parliament. An MP from Andhra Pradesh, Marjorie Godfrey, even asked the Indira Government to “put down the [duties] in the education syllabus so that children, as they come up to discharge the higher tasks, feel the duties of the citizens of this free country”.

But for the Opposition leaders such as PG Mavalankar, the government in 1976 was a “rump and rubber stamp Parliament”. “You say that Parliament is supreme, but it is a myth. Not only that, it is a dangerous doctrine. The concentration of power, centralisation of authority, shutting down all free opinion..and regimenting the citizenry—all these are on the Dictator’s Menu. They are certainly not on the Democrat’s table,” said Mavalankar in Parliament in 1976.

Parliamentarians were clearly in a high state of excitement over the amendment, whether they agreed with its scope or not. And this is precisely the problem the legal community and jurists had: that it was an amendment tailored by politicians.

Passed when much of the Opposition was behind bars, the 42nd Amendment was for all practical purposes intended to keep one party in power

– Alok Prasanna Kumar, Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy

The Swaran Singh Committee was set up by Gandhi in 1976 to make recommendations on fundamental duties — not even one of the 12 members was a legal scholar. Their report didn’t go down well with jurists.

Justice PB Gajendragadkar, the Chairman of the Law Commission, wrote a strongly worded letter to Indira Gandhi in 1976. The committee had “worked in a hurry,” he wrote, and “discussed issues in a casual manner and based its recommendations mainly on political considerations.” The fundamental law of the land should not be amended based on the views of a party committee, he continued.

Others also warned of the impact of the proposed amendments. Lawyer Nani Palkhivala wrote in the Illustrated Weekly of India, on 4 July 1976, that the Swaran Singh Committee’s Report on the amendments “will in reality change the basic structure of our Constitution”. However, he mourned the fact that “our monumental apathy and fatalism are such that the proposals are less discussed in public and private than the vagaries of the monsoon or the availability of onions.”

The basic structure he was referring to was crystallised by a 13-judge Supreme Court bench in the Kesavananda Bharati judgment pronounced in 1973, just two years before the Emergency was declared. It said that the ‘basic structure’ of the Constitution cannot be amended by Parliament. The 42nd Amendment tried to undo the judgment by amending Article 368—which provides the procedure for amendment of the Constitution—and adding a clause which said that constitutional amendments couldn’t be questioned in any court on any ground and that there is no limitation on Parliament’s power to amend the Constitution.

“Passed when much of the Opposition was behind bars, the 42nd Amendment was for all practical purposes intended to keep one party in power. But beyond that, it undermined institutions in one go by cutting down the power of the judiciary and limiting the scope of judicial review,” said Alok Prasanna Kumar, co-founder and lead of the Karnataka team at Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy.

Granville Austin, in his 1999 book, Working a Democratic Constitution: The Indian Experience also reflected on the 42nd Amendment. The American Indian Constitution expert wrote about how “the shift in the balance of power within the new Constitution made it all but unrecognizable”.

After the Emergency, the amendment took centre stage: what was going to happen to it? In an open letter published on 17 April 1977, Palkhivala reiterated that it violated the basic structure as laid down by Kesavananda, and that it wasn’t something the government could just gloss over. Others advocated the total repeal of the amendment. The Indian Express ran op-eds — like one on 2 November 1977 which declared that “The 42nd Amendment Must Go.” Eventually, the line followed by the Janata Party was changing the amendment by piecemeal.

A few amendments were undone by the Morarji Desai government through the 44th Amendment.

In fact, revoking the 42nd Amendment was part of the Janata Party’s manifesto before the general elections of 1977. And they were able to do it in spite of not having a two-thirds majority in the Rajya Sabha, according to then law minister Shanti Bhushan. This was because, as Austin noted, Congress MPs voted with the Janata government to repeal much of the 42nd and other Emergency amendments.

The Supreme Court, in its landmark 1980 Minerva Mills judgment, also struck down several amendments, including the ones made to Article 368 of the Constitution. The petitioners in the Kesavananda Bharati case, as well as the Minerva Mills case, were represented by Palkhivala.

Bhushan introduced the 44th Amendment to save the “basic structure of the Constitution” and uphold the power of judicial review of those laws that were curtailed by the 42nd Amendment. Under his stewardship, the Janata Party appointed a committee including Home Minister Charan Singh, I&B Minister LK Advani and Education Minister Pratap Chandra Chunder.

He told the Congress Leaders of the Opposition in both the Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha — CM Stephen and Syed Mohammed — that the Janata Party could have taken advantage of the 42nd Amendment in the way Indira Gandhi did. “They understood but were concerned about reversing their stand,” Bhushan said in a later interview.

But no one was concerned about reversing the 42nd Amendment, now being referred to in public discourse as the “mini-Constitution”. After a “two-day conference” with leaders of all political parties, during which every provision of the amendment was discussed, the 44th Amendment was passed unanimously. It undid several parts of the 42nd Amendment, but the duties remained.

Duties vs Rights

The balance between fundamental rights and fundamental duties hangs precariously on what—and who—defines the duties an Indian citizen has towards the Indian State.

The moral appeal of ‘duties’, despite their anxious political undercurrent, has remained in the public conscience. Moreover, having been borrowed from the erstwhile USSR’s Constitution, fundamental duties became a cosmopolitan legislation to have.

“We’re not the only Constitution that talks about Fundamental Duties. There is a tradition of sorts, [and] India only joined that tradition [in 1976],” said Sudhir Krishnaswamy, Vice Chancellor of the National Law School of India University. “There are two kinds of constitutions [that mention duties]. A socialist constitution like that of the erstwhile USSR. There’s also a Buddhist constitutional tradition that talks about duties. Constitutions like that of Thailand, Burma (now Myanmar), Bhutan might have a reference to duties.”

But the anxiety around the 42nd amendment comes from the fact that Indira Gandhi left some loose ends.

“What’s striking in the Swaran Singh Committee [suggestions] is that there’s no understanding of ‘duties instead of rights’ or ‘duties before rights’. None of that. It was just put into the Constitution,” said Krishnaswamy. “The interesting question is: What does the Indian Parliament think about duties? That is still an open question. It hasn’t been settled by any court. We’ve only been reminded that duties are important.”

And here the anxiety of the citizens overpowers the moral goodness of duties. “Fundamental duties were never meant to be a part of the Constitution. While there was some idea that citizens have some duties, they were never meant to be constitutionalised – the State should never have to infringe upon citizens’ rights,” said Krishna.

Guiding concepts like the Directive Principles of State Policy and the fundamental duties are not enforceable by law, calling into question whether or not they need to be enshrined in the Constitution of India.

“The Constitution is supposed to protect your rights against the government, tell the government the limits of its powers, not teach you how to be good citizens,” said Prasanna. “Fundamental duties were just ways for the Indira government to exercise greater control over the population. They fundamentally go against the ideas of the Constitution, as they perpetuate the idea that you exist to serve the State, not the other way around.”

The balance between rights and duties, therefore, can never be struck — the government’s hand will always be heavier.

Also Read: Nehru’s Hindu Code Bill vs Modi’s UCC— same script, same drama, different Indias

Need for constitutional literacy

Today, the invocation of fundamental duties has a far more sinister intention that goes beyond just constitutional complexities.

“In principle, the idea that everyone as a citizen owes duties to each other, which is essentially a sense of civic participation, and that the State owes duties to citizens, has deep roots in Indian philosophical thought,” said Arghya Sengupta, founder of Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy. “The Bhagavad Gita gave the idea of doing one’s duty, and there was Shriman Narayan Agarwal’s The Gandhian Constitution for Free India based on the idea of duty. So we’d been there before but these ideas were not taken up at the time of the drafting of the Constitution because they seemed too radical then.”

But they might not be as radical now.

In 2020, the RSS conducted a survey among youth between the ages of 18-30, the primary aim of which was to understand how to be a dutiful citizen, and how that citizen can contribute to society.

Fundamental duties were just ways for the Indira government to exercise greater control over the population. They fundamentally go against the ideas of the Constitution, as they perpetuate the idea that you exist to serve the State, not the other way around

– Vineeth Krishna, Center for Law and Policy Research

The discourse around duties to the State is so omnipresent that it has saturated RSS literature. Speeches and essays revolve around the Gandhian emphasis on duties and how there should be a constitutional update to match the changes in Indian society

“Thanks to the influence of Gandhiji and many other stalwarts of the Freedom Movement, our Constitution essentially carried forward the age-old spirit of democracy based on societal Dharma,” read a recent editorial in the Organiser, RSS’ English-language mouthpiece. “That is the original reason Constitution did not mention the alien concepts like ‘socialism and secularism’. Nehru brought this through his monopoly over the party structure and eventually made these as our national goals through education.”

But all the moral goodness and high language have given way to a threatening social order. An amendment that was introduced as a safeguard against “anti-national” activities is becoming a tool to sow intimidation. By using a non-enforceable framework like duties, the state can arbitrarily decide whether or not a citizen is doing their national duty.

“It’s not even a constitutional argument [anymore]. Now, it’s far bigger than the emphasis on duties — more about the political survival of the nation. Far more Hitleresque,” says Krishna.

The “Idea of India”, as enshrined in the Constitution and by the Constituent Assembly, has been dismissed as elitist and out-of-touch. The idea of the Indian State — and therefore the Indian citizen — has been in constant flux since then. One needs to look no further than the debates around the Citizenship Amendment Act and the National Register of Citizens for proof.

“In the last 75 years, we only kept talking about rights, fighting for rights and wasting our time,” Modi said at the launch of ‘Azadi Ke Amrit Mahotsav se Swarnim Bharat Ke Ore’ programme in January 2022. “The issue of rights may be right to some extent in certain circumstances, but neglecting one’s duties completely has played a huge role in keeping India vulnerable.”

Duties and rights are complementary to each other, according to Baxi. “Duties lead you to rights. In order to perform my duties as a citizen of India, I need certain freedoms that can be guaranteed by the State,” said Baxi.

This is something Modi agrees with as well. “That rights and duties get spoken of together is itself a mistake. It implies that rights are one system and duties are another system. It is not like that. Everybody’s rights are embedded in our duties. Mahatma Gandhi used to say moolbhoot adhikar nahi hote hai, moolbhoot toh kartavya hote hai (rights are not fundamental, it is duty that is fundamental),” he told students at New Delhi’s Talkatora Stadium in January 2020.

But this argument is a shot in the dark without constitutional literacy, according to legal experts like Baxi. At a time when India is brimming with its own potential — and simultaneously turning inwards and redefining what it means to count as an Indian citizen while stepping onto the global stage — enforcing duties without honouring the rest of the Constitution could lead to a dangerous concoction of nationalism and moral censorship.

“Duties turn citizens against each other. So, instead of the State that can’t surveil every aspect, you have people doing that job,” said Krishnaswamy, adding something a colleague mentioned to him: “Duties are something we owe to each other, not to the State.”

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)