If I had given in to the celebrity syndrome of sitting in my ivory tower and having my largesse delivered to the needy by remote control, I would never have come face to face with the trauma of the migrant workers or understood that a food packet was a woefully inadequate substitute for a ride back home.

When my neighbour Ajay Dhama drove me down to Thane that day, I comforted myself with the thought that I’d be doing the soul-cleansing service of distributing food packets and other essentials among the migrants, who were meant to walk all the way back to their villages. But I was unprepared for what lay before me. It was despair—up, close, personal and disturbing.

There was confusion and chaos, emotional and practical. Thousands had begun their padyatras, their long journeys on foot, some cradling children in their arms, others carrying their elders on their shoulders. Husbands walked ahead, holding tiffin carriers and water bottles. Wives followed, their heads covered with the sari or dupatta, holding their children, bracing themselves for the harshness of the sun and the darkness of the night.

We encountered a medley of deeply perturbed faces drawn, none of them wearing a smile, not even one of hope. People from various castes, regions and professions were present. Some willingly put out their hands for the food we were distributing. Others hesitated. Their gaze held several unasked questions. Perhaps it was my imagination at work, but I was hit by this disconcerting feeling that someone in that crowd was asking me, ‘Do you really think that by handing out these packets, you’ve done enough? You’ve assuaged your soul?’ It was my mind playing tricks, my conscience rubbing its eyes and waking up. No one asked me any questions. It tickled them to find a face they recognized, a celebrity in their midst. But honestly, beyond that my presence gave them nothing.

Something that struck me, and is stuck in my mind even now, was the vast sea of humanity before me. I was, at first, taken aback by the sheer number of people on the roads. Innumerable people on the highway, below bridges, on the sidewalks, social distancing a distant dream. Some were squatting, others standing, restless and yet resigned to their fate.

For distribution at Kalwa Chowk, we had carried a couple of truckloads of food, water and basic essentials for 48,000– 50,000 people. On average, we were handing out two packets to each person when some of the migrant workers requested me for enough food to tide them over for ten days. It seemed odd to me that they were asking me for food that would last so long. So I asked them, ‘Why would you want food for ten days?’ They explained that they were going on foot to their homes in Karnataka, a journey of at least ten days. And it was then that the reality of their ordeal hit me. It stumped me. There were 350 people there, all set to walk home.

‘I met a family with an elderly lady and a little girl. When I asked them where they were going, they said, Karnataka. I told them to hold on for two days; I would see what I could do. And thus began the chain to set the whole process in motion,’ I said to senior journalist and author Bharathi S. Pradhan, for her Sunday column in the Telegraph.

Also read: ‘Time to come home’ — Sonu Sood announces charter flights for students stuck in Kyrgyzstan

The number 350 was just the beginning. There were thousands more waiting in hope, because as the days passed, more and more people came to Kalwa Chowk, which was a kind of stopover on their journey by foot. There were batches heading in different directions to Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand and other states.

‘Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country.’ Inspired by John F. Kennedy’s epochal words, a transformative thought began to take shape inside my head. For one thing, it became amply clear to me, and I admitted it to myself, that what I was doing was definitely neither adequate nor a solution to the real problem that loomed large on the highway. I couldn’t possibly sit back smugly about distributing ‘brown paper packages tied up with strings’.

The corollary to the first thought was that newfound wisdom had to translate into action. My strength, my star power, the privileged position of being a public face had to be put to worthwhile use.

Once I’d cleared my head, I dialled Neeti Goel, a restaurateur-friend who became a front-foot player alongside me in the movement. Putting two heads together instead of relying on one was the wiser way of coming up with a practical, doable plan to provide the right salve for stranded migrant workers. In the course of my conversations with her and a couple of other friends, I decided I was going to stick my neck out and go the whole hog.

I was going to put wheels under the feet of the people who wanted to go home. When I asked the workers who were going to Karnataka to give me two days to find them a better way of reaching their destinations than journeying on foot, they were at first mistrustful. They had been left to their own devices and were so helpless that they didn’t dare to even hope someone cared enough to actually shepherd them home.

They were impatient, they were disbelieving. Many said they would walk home. Others told me they would cycle all the way. Realizing how onerous the task before me was, I requested them to be patient with me. I put my persuasive powers to good use, assuring them that though it would take a couple of days for me to organize a ride for them, it would come through. I would make sure I got them to their destinations more comfortably than they could imagine.

It was an impromptu but impassioned plea. And, like Shah Rukh Khan’s dressing-room speech in Chak De! India, it had an impact. They agreed to wait and gave me a chance to prove that I meant what I said.

Also read: Rana Ayyub to Vikas Khanna, many stars in lockdown crisis. But BJP loves only Sonu Sood

With many of them, I had a one-on-one conversation. I conveyed to them that they were the heartbeat of our nation. I said, ‘You helped build our bridges, roads, homes, hospitals, religious places, schools and even our courts. It is your sweat and blood that has gone into our infrastructure. Today, when you are literally standing stranded on the crossroads, fearing there is no one here for you, I’m with you. The least I can do is to flag off your journey.’

The visuals of crowds stretching for miles—of lockdown-beaten migrants walking homewards, families moving en masse with the elderly who could barely walk—made it difficult for me to shut my eyes. Sleep played hide-and-seek with me as I became more aware of what was happening out there on the roads of my country, my state, my city.

Questions that whirred in my head: How could we allow those who helped build our homes to not reach their own homes? How could we turn away unaffected from their trauma, as if it had little to do with us?

American entertainer Lily Tomlin was spot on when she said: ‘I always wondered why somebody doesn’t do something about that. Then I realized I was somebody.’ I realized that I was not merely somebody but a fortunate somebody who had a voice and the means to ‘do something about that’.

But, as I told Lachmi Deb Roy of Outlook magazine, ‘Initially, I didn’t have any idea how to make arrangements to send migrant labourers home.’ I had sheltered the first 350 in a school, having promised them that I would personally organize buses to ferry them home. I also assured them that they would get food and other amenities while they waited for the transport to arrive.

This was where the Ghar Bhejo movement, the ‘Send Them Home’ mission, really began. At that juncture, I didn’t know how far or how wide the movement would carry. But carry it did.

As the movement gained momentum, and word spread like wildfire that I was not making empty promises but was actually making transport available for migrants, they came in droves, looking for me and my representatives. Hundreds of requests came each day, thousands each week. My inbox and WhatsApp messages overflowed. At one stage, my inbox had over 3500 mails from various people. I don’t know where they got my email ID from, but I was inundated with mails and started to lose track. Neeti, Sonali, my kids, everybody joined in. My chartered accountant, Pankaj Jalisatgi, stepped in with his team of four. The four multiplied into twelve Ghar Bhejo volunteers.

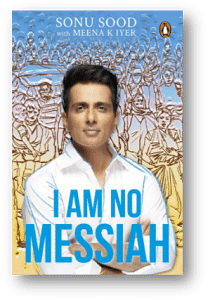

This excerpt from ‘I Am No Messiah’ by Sonu Sood and Meena K. Iyer has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.

This excerpt from ‘I Am No Messiah’ by Sonu Sood and Meena K. Iyer has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.

The title of this book suggests that the author suffers from severe megalomania.