The corruption issue surfaced again in July 2013 when the Supreme Court pronounced judgement on a PIL protesting that legislators convicted of a criminal offence could continue functioning as legislators as long as they had appealed against the conviction and the appeal was pending. A surprisingly large number of legislators had avoided disqualification because the process of appeals took a long time. The Supreme Court put an end to that practice by pronouncing that, henceforth, legislators would be disqualified immediately on conviction, even if the conviction was appealed in a higher court.

The ruling was prospective, but it posed a threat to Lalu Prasad Yadav who had been elected to the Lok Sabha in 2009, and was an important ally and firm political supporter of Sonia Gandhi. He was being tried on various fodder scam cases pertaining to his years as CM of Bihar and the judgement on one of these cases was expected on 30 September. If convicted, he could be disqualified from sitting in Parliament and standing for elections.

The Government responded to the Supreme Court judgement by introducing a Bill to amend the Representation of the People Act 1951 to give convicted legislators the limited privilege of participating in the proceedings of the legislature but without the ability to vote until the appeals process was completed. The Bill was being considered in the Rajya Sabha but in the face of strong opposition, the Government agreed to refer it to the Standing Committee. As it was unlikely to be passed soon, the Government decided to introduce an Ordinance, which would later have to be ratified by Parliament.

The case for the proposed amendment was that politicians were vulnerable to politically motivated charges and the system could be manipulated to secure a conviction at the local level. Justice could only be assured by appealing to a higher level, but the process took so long that disqualification on first conviction was felt to be too strong. That said, resorting to an Ordinance could only be justified by some element of urgency, and the only urgency was the impending judgement in the Lalu’s case. The decision to move for an Ordinance was strongly criticized by the opposition even as it was vigorously supported by senior members of the cabinet.

At this stage, Congress Vice President Rahul Gandhi took an unusual step. The party has organized a press briefing on 27 September to explain the rationale for the Ordinance. Rahul made an unscheduled appearance at the briefing and announced that he was personally opposed to the Ordinance. He referred to it as ‘a piece of nonsense that should be torn up’. He went on to say it was the sort of compromise with corruption that all parties resorted to, but it was time to stop.

Many young people approved of Rahul’s stand. However, leading members of the BJP asserted that the Congress vice president had demeaned the office of the PM, who was on an official visit to the US, and called upon Dr Manmohan Singh to resign. The press had a field day presenting Rahul’s action as a direct attack on the authority of the PM. The latter was in New York at the time and issued a characteristically mild statement that the Congress vice president had written to him expressing his views, and the matter would be discussed in the cabinet on his return.

Also read: I felt very strongly that Rajiv Gandhi was not corrupt: B. Raman on the Bofors scandal

AN IMPORTANT FAULT LINE EXPOSED

I was part of the PM’s delegation in New York and my brother Sanjeev, who had retired from the IAS, telephoned to say he had written a piece that was very critical of the PM. He had emailed it to me and said he hoped I didn’t find it embarrassing! Sanjeev had been quite unsparing. He said the PM had betrayed himself time and again by turning a blind eye to goings on around him. He also said that when he took up the office, he became ‘our’ PM and not the Congress party’s representative. He went on to say it was not too late to resign: ‘Rahul is ripe to take over and we would all welcome his coming out of the shadows.’ It was strong, no-holds-barred stuff and, not surprisingly, Sanjeev’s article was widely reported in the press with reference to him being my brother.

The first thing I did was to take the text across to the PM’s suite because I wanted him to hear about it first from me. He read it in silence and, at first, made no comment. The, he suddenly asked me whether I thought he should resign. I thought about it for a while and said I did not think a resignation on this issue was appropriate. I wondered then whether I was simply saying what I thought he would like to hear but on reflection I am convinced I gave him honest advice.

The incident was still a hot subject of discussion when we returned to New Delhi. Most of my friends agreed with Sanjeev. They felt the PM had for too long accepted the constraints under which he had to operate and this had tarnished his reputation. The rubbishing of the Ordinance was seen as demeaning the office of the PM and justified resigning on principle. I did not agree. Rahul’s action was certainly embarrassing and unseemly. He himself admitted this publicly a few days later in Ahmedabad, when he said, ‘My mother told me that the words I had used were wrong. In hindsight, maybe the words I used were wrong, but the sentiment was not wrong. I have a right to voice my opinion. A large part of the Congress party wanted it.’63 The PM also told me that Rahul had called on him personally after he returned from the US to express his regrets and say he meant no disrespect.

I did not think the incident called for a resignation from the PM. Running a coalition government obviously meant making many compromises. In such a situation, it was essential for any holder of political office to resign if political compulsions were pushing them to act differently from what was right. The PM’s offer to resign on the issue of the nuclear deal belonged to this category. Resigning because Rahul had rubbished the Ordinance publicly did not. In fact, his opposition to the Ordinance was, if anything, a principled position against tolerating corruption. Resigning on that issue would either look as if the PM was determined to help convicted politicians, even when his party was willing to change course, or be seen as acting out of pique.

Also read: How Manmohan Singh played a key role in India signing its first bilateral investment treaty

In a way, the incident highlighted an important fault line in the UPA. The Congress saw Rahul as the natural leader of the party and wanted him to take a larger role. In this situation, as soon as Rahul express his opposition to the Ordinance, senior Congress politicians, who had earlier supported the proposed Ordinance in the cabinet and even defended it publicly, promptly changed their position. I had always felt it would have been much better if Rahul had agreed to join the cabinet. The PM had repeatedly asked him to do so but he had preferred to stay out on the grounds that he wanted to strengthen the party. This was an important objective. But given his political position in the party, joining the cabinet would have created a greater sense of political cohesion in that body. Congress cabinet ministers would certainly have looked to him for the signals, but the arrangement would have strengthened the cabinet as long as the PM and Rahul were seen to be on the same page.

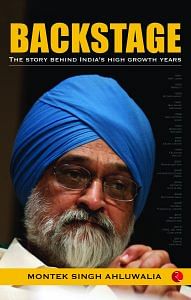

This excerpt from Backstage: The Story Behind India’s High Growth Years by Montek Singh Ahluwalia has been published with permission from Rupa Publications.

This excerpt from Backstage: The Story Behind India’s High Growth Years by Montek Singh Ahluwalia has been published with permission from Rupa Publications.

70 years late and Billions of dollars short.

Until Sonia leaves this world, Congress party has no future. As long as she is alive, she will never let anyone take the mantle of the party, and that will ensure BJP wins again and again.

At some point – people more knowledgeable than me will locate it more accurately – Dr Singh got too comfortable in his chair to ever think of resigning on a point of principle. He did not lift a little finger to push reforms, something on which the columnist could have assisted him. He allowed all manner of egregious graft and wrongdoing to proceed unhindered, taking care to keep himself at arm’s length. A watchman who felt satisfied that he himself was not carrying stuff out of the godown.