The first post-WWII Prime Minister of Japan to visit India was Abe’s grandfather, Nobusuke Kishi, who travelled to New Delhi in May 1957 soon after becoming Prime Minister. Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru reciprocated by paying a return visit within months, visiting Tokyo in October 1957. These visits in fact culminated a decade of partnership. After Independence, India had reached out to a beleaguered but industrially advanced Japan and received their support for India’s quest for development. Kishi and Nehru painted not just on an empty canvas but also on a wide one. Their joint statement read: ‘The Prime Ministers consider that the economic development of Asian countries, which had been neglected during past centuries, is essential for the peace and stability not only of Asia but of the whole world.’

It was Mikio Kato, director of the International House of Japan in the 1980s, who referred to the 1950s as ‘the post-war golden age’ in the bilateral relationship. ‘When we look back over Indo–Japanese relations of the post-war period,’ Kato told a semi-official conference on bilateral relations held at the India International Centre in New Delhi in 1986, ‘the fifties and sixties stand out as an era of enthusiasm, a quality which existed on both sides, particularly perhaps on the Japanese side.’

Three factors defined the early and great optimism of the 1950s in the bilateral relationship generated by the Nehru–Kishi partnership. To begin with, an immediate consideration was that India had established a bond with post-WWII Japan by distancing itself from the victors of WWII. An Indian judge, Justice Radha Binod Pal, submitted a dissenting judgement at the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal and India signed a separate peace treaty with Japan. India also became one of the first countries to extend diplomatic recognition to Japan. Prime Minister Kishi was also grateful to India for Nehru’s ready willingness to accept Japanese official development assistance, signalling Indian regard for Japan.

The early post-Independence Indian enthusiasm towards Japan was shaped not just by the fact that Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose had allied himself with Japan and established the Indian National Army with Japanese assistance but also by the even more enduring fact that as Asia’s first industrial and modern nation, Japan had inspired Indian national leadership.

Also read: MN Roy was to Marxism what Vivekananda was to Hinduism. He separated spirit and form

One of the first Indian nationalists to draw attention to Japan’s rapid rise was Swami Vivekananda. On his way to Chicago in 1893 to deliver his historic address to the Parliament of Religions, Swami Vivekananda opted for the Pacific route. Stopping in Japan enroute to Vancouver, Swamiji became fascinated by what he saw. ‘The Japanese seem now to have fully awakened themselves to the necessity of the present times,’ Swamiji said in an interview after his visit. ‘They have now a thoroughly organized army equipped with guns that one of their own officers has invented and which are said to be second to none. Then, they are continually increasing their navy. I have seen a tunnel nearly a mile long, bored by a Japanese engineer. The match factories are simply a sight to see, and they are bent upon making everything they want in their own country.’ Swamiji wanted young Indians to be sent to Japan to be educated in modern technology and manufacturing.

On his onward journey from Yokohama to Vancouver, Swamiji travelled with the industrialist Jamshedji Tata. In conversations on the ship, the two shared their admiration for Japan’s industrial development and modernization. On his return to India, Tata wrote to Swamiji that having been inspired by their conversation, he was going to fund a science research institution. The Indian Institute of Science in Bengaluru was that institution.

Mokshagundam Visvesvaraya, an engineer and a promoter of industrialization, visited Japan in 1898. Visvesvaraya was one of the founders of the Institution of Engineers and the Mysore Chamber of Commerce. He gave the Indian national movement the slogan ‘industrialize or perish’. After his tour of Japan, Visvesvaraya wrote extensively on the lessons India must learn from the modernization of Japan. He was impressed by Japan’s development of schools, transport and communication and their role in Japan’s industrial development. He was convinced that investment in education was the key to economic development. In 1916, Rabindranath Tagore travelled to Japan and was equally impressed by its modernization as well as its preservation of tradition.

Finally, Jawaharlal Nehru himself wrote eloquently about Japan’s victory over Russia in the 1905 Russo–Japan war, noting that it was a historic moment when an Asian nation had defeated a European one, turning back the tide of European colonialism. This appreciation of Japan by eminent Indians from the fields of philosophy, religion, literature, engineering, science and politics shaped popular regard within the Indian national movement for Asia’s ‘first industrial nation’.

Also read: Nehru even asked children to ‘break their gullaks’, provide support during 1962 and 1965 wars

It was therefore understandable that Prime Minister Kishi arrived at New Delhi in 1957 to a very friendly reception, which cemented an early bond between Asia’s new democracies. Nehru introduced him at a public meeting in Delhi saying, ‘This is the Prime Minister of Japan, a country I hold in the greatest esteem.’

A Japanese businessman by the name of Toshio Yamanouchi arrived in India in the 1950s seeking to explore the promised business opportunities. He remained in India till the mid-1970s. In his fascinating autobiography, India Through Japanese Eyes, he writes, ‘The Nehruvian age was a bright period for relations between India and Japan … Japan gave first pledge of Yen credit to India in 1957 and till Nehru’s death in 1964 as much as 60 per cent of Japan’s total Yen credit went to India.’

A credit of up to 18 billion yen was extended to enable India to import equipment for railways, hydro and thermal power, ships and ports, along with other industrial machinery, machine tools, rayon and fertilizer.10 The Indian Planning Commission set up the Committee for Studies on Economic Development in India and Japan under the chairmanship of C.D. Deshmukh with P.C. Mahalanobis and Bharat Ram as members and the economist Jagdish Bhagwati as member-secretary.

The committee members travelled to Japan and interacted with policymakers and analysts in Tokyo. However, even though on the Japanese side the committee’s interlocutors included the influential Dr Saburo Okita, an academic who had served a brief term as foreign minister, Bhagwati recalls that very little came of it after the initial enthusiasm of the 1950s. The committee remained dormant in the 1960s and was only revived in 1973 after the first oil shock.

As many analysts have noted, the enthusiasm of the 1950s was soon dissipated, with Japan and India finding themselves in different camps during the Cold War era. Apart from the Cold War, bureaucratic and diplomatic inertia in both capitals may have also played a part. Tokyo was focused on the US, East and Southeast Asia, while New Delhi looked West. Two highly regarded scholars of India–Japan relations, K.V. Kesavan and Takenori Horimoto, point to the geopolitical differences during the Cold War, accentuated by Japan’s concerns with India’s proximity to the Soviet Union as creating a distance between the two Asian nations.

Yamanouchi describes the post-Nehruvian period as one of ‘high hopes and frustrations’ and of ‘uneventful tranquillity’ in the bilateral relationship, blaming both the geopolitics of the Cold War and the economics of India’s ‘License-Permit-Control Raj’ for this. Defeated and occupied by the United States, Japan remained firmly under the US umbrella, while a newly liberated India refused to join any military alliance and opted for a policy of non-alignment.

India became distanced from the West and its allies on account of both Cold War geopolitics and its own inward-looking industrialization strategy and the adoption of what has been called ‘bureaucratic socialism’. As Kesavan notes, Indian policymakers increasingly viewed Japan as a ‘client state’ of the US, while Japanese public opinion saw India as just another third-world country incapable of getting its act together.

It was not surprising, therefore, that after the 1961 visit to India by Kishi’s successor, Prime Minister Hayato Ikeda, no Japanese premier visited New Delhi for over two decades. The hiatus finally ended in 1984 when India began liberalizing its foreign investment policy and Osamu Suzuki chose to enter India’s automobile sector.

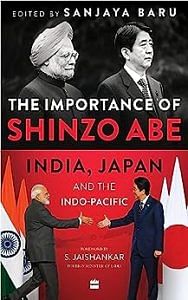

This excerpt from ‘The Importance of Shinzo Abe’, Edited by Sanjaya Baru has been published with permission from Harper Collins Publishers India.

This excerpt from ‘The Importance of Shinzo Abe’, Edited by Sanjaya Baru has been published with permission from Harper Collins Publishers India.