Some of my confusion around a politician’s behaviour was cleared when I had an opportunity to catch up with a politician on a morning walk. That politician happened to be a sitting MLA of a district town, where I happened to serve as the SP. After the walk, he forced me to join him at his house, adjacent to the ground, for a cup of coffee. I relented, and when we reached his place I was astounded to see the sheer number of people waiting for him there—easily close to a hundred-odd people. I understood later that this was his version of the janata darshan (people gathered to get their grievances addressed). Uncomfortable as I was, I still went in for that cup of coffee. I also asked him whether that big a crowd was a regular feature of his mornings. He said he saw close to 120 people on normal days. With my curiosity piqued, I told him that I was very interested in watching him interact with the people. He gamely agreed. What I saw for the next one hour changed my impression of public service in India and the role of politicians in it.

I saw the MLA handle most of the issues deftly for almost an hour. He even called up the local sub-inspector for a work which was not fully legal in its scope as well. He must have seen close to twenty- five people in an hour. His personal assistant had also quickly filtered out people and he made a couple of calls at his level to bring down the numbers. Invariably, all of them were offered upma, a south Indian breakfast and a cup of coffee and most people had their breakfast there.

As a country that is in the process of improving its social security net by offering an economic cushion to the needy ones, a lot of people suffer simply because something bad has befallen them and they need that instant and immediate help. Most of the issues belonging to the public needs are matters that an efficient officer should be able to solve. With brokers rife in most government offices, even for genuine cases, people are forced to resort to a politician’s support as they perceive them as people who can get the job done. In a faulty democracy, a politician becomes the go-to man for most people as he is most accessible and will get the job done for the immediate reward of their votes. When I asked him why did he call the sub-inspector, knowing fully well that his request was borderline illegal, he plainly answered that he just took his chance with that officer.

Also read: Former IPS officer’s tell-all memoir unveils ‘real-life Singham’ behind the khaki uniform

Later, in a separate context, another MLA similarly spoke to me of the daily expenses that he normally incurred. I instantly remembered the scene of breakfast being served in the previous story and told him about it. He was telling me how food played a major role in his house every day and later I gathered that many politicians have to run their houses like a canteen, serving breakfast, lunch and dinner. This expense alone could run into a couple of lakhs every month. He also mentioned about the other ‘incidental’ expenses he was forced to partake in. According to his accounts, he visited an average of around ten marriage ceremonies every day in a wedding season, and multiple deaths every week.

I have also had the misfortune of meeting some of the absolutely rotten politicians. Their demeanour, language and thinking are, at least, a century old. They still maintain their hold on their constituency by utilising the fault lines of caste and the lack of exposure to the wider world of their people. All of them need to go, and undoubtedly, they will slowly go as the society has its own way of weeding out the bad ones.

Once we make it a habit to study people with all their complexities, it will really be easy for us to deal with our fellow beings, even politicians.

It was clear to me by now (as I hope it is to you) that all politicians aren’t bad. In fact, I had seen an equal number of rotten officers as rotten politicians. There are officers who had made it a habit to sell almost all of their signatures with their integrity at the lowest. They are more threatening to the system as they directly lord over it without any adequate check and balance. I also felt it was always my duty to course-correct politicians when they stepped completely out of line. I could do this with a well-meaning politician but not with an officer whose pay grade was way above mine. A bad politician was judged every five years at the ballot box and an officer none.

Also read: It’s 2021 and the Indian bureaucracy remains the greatest impediment to progress

I can categorise the interactions of the politicians with a civil servant into three parts—legal requests, requests bordering on illegality and blatantly illegal requests.

If it was a legal request, they were more forceful as that request was made as a matter of right. I normally went all out to help him so that I could use the genuine favour as a bargaining chip later. For requests bordering on illegality, I tried and educated them on how their requests couldn’t be carried out and even if they were, the actions had consequences. A simple example for this could be extending the timing of the loud speaker beyond 10 pm (most state laws stipulate it to be till 10 pm).

Any request that was blatant in nature was denied by me instantly. A firm no conveys a very strong message; I found that procrastinating on this by saying things like, ‘I will look into it’; ‘give me some time ’, ‘I’ll try my best’, and other things, only built up undue expectations which only got busted in time. A firm no conveyed decisiveness which helped in future dealings.

Whenever I got an opportunity to meet any unruly politician, I always made it a point to have a conversation about the blatantly illegal requests that were made and I tried and explained how it was problematic for everybody to act on it. One bad decision is enough to ruin any ones life built very meticulously. I always felt that conversations of this nature go a long way in building a good rapport.

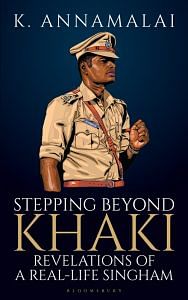

This excerpt from ‘Stepping Beyond Khaki: Revelations of A Real-Life Singham’ by K. Annamalai has been published with permission from Bloomsbury India.

This excerpt from ‘Stepping Beyond Khaki: Revelations of A Real-Life Singham’ by K. Annamalai has been published with permission from Bloomsbury India.