In her new book, Sharmila Sen remembers the strangeness of encountering a new cuisine full of processed foods.

In the early 1980s, Indian grocery stores were mostly located in distant Boston suburbs where the nascent Indian immigrant community lived. We did not own a car and reaching these stores was nearly impossible. In the Star Market near our apartment, Ma found some turmeric and a few sticks of cinnamon in Durkee jars. She found rice and some lentils. The rest she would have to improvise. Ma had dropped out of college at nineteen to marry the brother of one of her classmates. Until she arrived in the United States, she had been a Bengali housewife. Now she had a part- time job in a Harvard library (soon to be turned into a full-time job).

During the day, she shed her usual sari, wore hand-me-down trousers and blouses, and walked to an office where she would have to converse in English. She managed with smiles and gestures when her wobbly English failed her. In the evenings, she tried to transform American supermarket chicken into something resembling a Bengali murgir jhol, a chicken curry. Soon Baba would start returning home— frustrated, angry, tired— demanding that we eat “American food” instead of our improvised Indian meals.

I will never know for sure what happened to him in his new job. The clothing shop sold very expensive men’s suits for Boston Brahmins. It was owned by an Armenian American and the tailors who did the alterations upstairs were recent immigrants from Italy. Sales were handled by an Irish American and an Italian. It was and continues to be a very elite, white, male store. A stone’s throw from Harvard Yard, the store dressed the most successful WASPs of the city and was run by white men who did not possess Ivy League degrees and were never allowed into the club themselves. In 1982, add to this volatile mixture an Indian man. None of them had worked closely with an Indian before, or been to India. Their knowledge of Indian food was limited to the one or two curry restaurants dotting the Central Square area of Cambridge. Often Baba would come home from work, after a day- long tutorial on the merits of the two- button, side- vented jacket, or after mastering a proper four-in-hand, a half Windsor, or a full Windsor, and repeat the lines he had heard at work from his coworkers. “Cumin smells like armpits.” “Cilantro is revolting.” Suddenly, jeera and dhania— cumin and coriander, the beloved staples of an Indian spice box— became offensive.

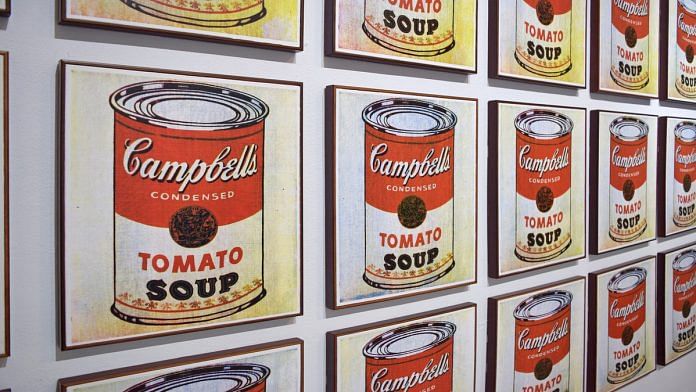

Thus began our great experiment in “American cuisine,” which we really understood to mean “white people’s food.” While I was scanning every entry in the 1968 edition of the World Book Encyclopedia, a set we had bought for a few pennies at a yard sale, Ma began looking for recipes on the backs of boxes and cans. Bisquick boxes and Campbell’s soup cans were especially helpful. All sorts of tasty casseroles and baked items could be created by adding Campbell’s mushroom soup or some powdered Bisquick mix to prosaic, cheap ingredients. Because we thought white people always had a soup course, we started each dinner with soup. Ma found that ramen noodle packets sold ten for a dollar. We shared one ramen noodle packet, ladled into three blue melamine bowls, at the start of each dinner at our kitchen table (there was no separate dining room table). We ate our meals with spoons, forks, and knives, Western-style. The soup was followed by broccoli and chicken, bathed in Campbell’s condensed mushroom soup, covered in Kraft shredded cheddar cheese, and baked in the oven. Jell-O was a frequent dessert. It was also cheap. Our supermarket cart in those days contained things like cans of Spam, the cheapest brand of baloney, squishy white bread, Kraft cheddar cheese, Little Debbie snack cakes, Entenmann’s doughnuts, lots of Campbell’s soups, Bisquick, Jell-O, Cool Whip, and dozens of packages of ramen noodles.

E.M. Forster once wrote that the English in India ate the food of exiles cooked by natives who did not understand it. We, a newly arrived immigrant family, ate what we thought was the food of Americans and cooked without understanding it. General Mills and the Campbell’s Soup Company were our local guides. And we stopped eating our own food, which we did understand, for a while, because someone had taunted Baba by saying cumin smelled of armpits.

White people’s food seemed to come in three colors— green, red, and white. Salads were green. Salads were also new to us. Though we ate a wide variety of vegetables in Calcutta, raw vegetables were rarely served as anything other than a garnish. My palate was unaccustomed to something as exotic as a bowl of raw lettuce drizzled with a pungent, unctuous liquid. Once I was served this kind of a dish with small cubes of toasted bread, pieces of bland chicken, and a few tiny fish. It was called a chicken Caesar salad. I found it revolting. We never ate chicken that was not marinated in at least four types of spices and grilled in a clay oven or braised in a curry. I grew up in a rice- and-fish culture, but the anchovies were hard to stomach. We were freshwater fish eaters. Salmon and cod did not suit our tastes.

The red foods were pizzas and pastas. These were easier on my palate, but it still took me the greater part of two years to appreciate oregano. I might have been an aficionado of the masala dabba, the Indian spice box, but I was scared of new spices from other lands. The white foods were easiest to like. Mac and cheese, Ma’s casseroles doused in Campbell’s condensed mushroom soup, grilled cheese sandwiches— it required relatively little effort to develop a taste for such food.

Most of what Ma cooked included processed food. Bits and pieces from cans, boxes, and packets. These packages were beautiful. In Calcutta, our kitchen larder rarely had so many brightly labeled cans and boxes. Processed foods would invade Indian homes from the 1990s onward, after liberalization of the economy enabled foreign brands to penetrate the Indian market. There are two American dishes that Ma made from scratch during our first years that stand out in our family’s collective memory. The Architect’s wife taught Ma how to bake macaroni and cheese using freshly grated white cheddar, cream, and lots of butter. The cheesy elbow macaroni, topped with golden bread crumbs, was easily one of our new family favorites. The other dish was saved for weekends and special occasions. Ma had become friends with an older black woman in her office. Enid used to bring a date nut bread, her signature dessert, to office potlucks and one day she wrote down the recipe for Ma. I will always remember Enid’s date nut bread as the first American dessert we learned to bake from scratch.

Enid told Ma that the bread had to be baked in an old coffee can. I marveled at her ingenuity because when the dark brown bread slid out of that coffee can it was shaped like a fat cylinder, complete with tiny ridges around the middle. Ma and I followed Enid’s recipe carefully. Dates were chopped precisely. The walnuts were broken into small pieces. We used brown sugar, never white sugar. The Folgers coffee can was greased liberally with butter. After the cake came out, we served it with softened Philadelphia cream cheese. I had tasted nothing like this in Calcutta. We would not have learned the coffee can trick, grasped the importance of brown sugar, or discovered that tangy, salty cream cheese pairs so well with a sweet bread, if it was not for Enid’s generosity. Hers was the first recipe we received in writing when we came to America. Now I realize that it was a bit of American cultural memory, written down and shared with a newcomer.

This excerpt was taken from the book ‘Not Quite Not White: Losing and Finding Race in America’ by Sharmila Sen. It was published by Penguin Random House in 2018.

This excerpt was taken from the book ‘Not Quite Not White: Losing and Finding Race in America’ by Sharmila Sen. It was published by Penguin Random House in 2018.

americans dnt know the imp of spices we indian use thats why they come with all sorts of misconceptions about indian food as whole world knew 1st world countries tend to end up in horrifying cancers of all sorts which we asians dnt have

1st World Country Problems..

Disgrace Indian foods is the best come to my home I will serve any Americans let them give the verdict. Indian cuisine the best in the world.India is great.