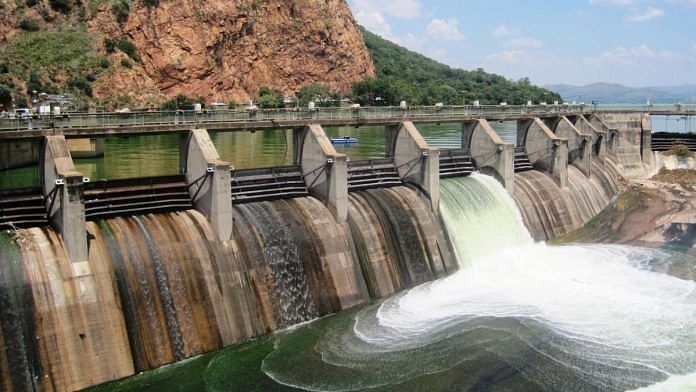

On May 19, 2018, the Prime Minister of India, Narendra Modi, inaugurated the Kishanganga hydropower project and dedicated the project to the nation. In 2016, the Bursar hydropower project was declared a national project (Parvaiz, 2018). These two hydropower projects, each located in Kashmir Valley and Chenab Valley respectively, seem to have been bestowed with the distinction of embodying India’s technological progress and nationalism.

The act of being declared a ‘national project’ has far-reaching consequences. Such a project will be expedited at all levels, and financial assistance will be provided by the Union Government of India to the extent of 90 per cent of the estimated cost in the form of Central grants (MoWR, 2017). It also means that the project will be fast forwarded; it also removes whatever procedural limitations are otherwise applicable on its execution (MoWR, 2017).

Such a distinction of declaring a project of national importance or dedicating a project to the nation is not a stand-alone decision. It has a context and particularity that necessitates such an act on the part of the Indian State. Whether it is the Kishanganga hydropower project or the Bursar project, the value of these undertakings is beyond economic or developmental for the Indian nation-building endeavour.

These projects are an embodiment of control and domination over the disputed territory of Jammu and Kashmir and its waters. The presence of Indian labour and administrative officers in the remote regions of Jammu and Kashmir, from Gurez in the extreme northwest to Kishtwar in the extreme east, shows how even the most difficult of terrains is not immune to bureaucratic and administrative penetration, and that the state legibility of these remotest of places is possible.

This is a manifestation of state policy wherein politics and political interests in the region take precedence over the ecological and social fragility, and vulnerability that such projects cause to people and their habitats. In this essay, we focus on the contextual and structural factors which influence the decision-making and planning of development work such as hydropower projects in Jammu and Kashmir.

By examining outcomes such as dispossession, displacement, loss of livelihood, migration and environmental effects, this research brings into notice how laws and policies governing development are disembedded and utilitarian in nature, how development is political and how the affected people are deprived of their share in decisionmaking over their resources.

This, in turn, helps us reflect on how control over territories and people is produced, performed and reproduced through developmental policies.

Also read:

Development through Dams: By Whom and For Whom

‘Water is renewable, yet the dams are not,’ McCully (1996) notes in Silenced Rivers: The Ecology and Politics of Large Dams. Dams and hydro-power projects became part of India’s nation-building exercise after independence in 1947. India embarked on the journey of nation-building, of which planned development was an integral part (Mohanty, 2005).

The planned development was conceptualised and executed through Five Year Plans, which essentially focussed on economic development for which factories, dams, and mining all became necessary interim goals (Kaviraj, 1996, p. 116). While dams were referred to as the ‘temples of modern India’ (Mohanty, 2005), at the same time they became the cause for forced dispossession and displacement of millions of people from their ancestral lands and regions (Gupta, 2012; Ramanathan, 1996).

The temples, hence, brought doom to the people instead of faith and liberation. What is true of the doom brought by dams in India at large reveals itself in the same ways in the disputed territory of Jammu and Kashmir. The dispossession and displacement caused by the acquisition of land for hydropower projects in the state has led to the disempowerment of a large section of society, to whose existence and identity, land is an integral part. The land taken away from them has come to them after a long struggle against the despotic, exploitative rule and land regimes that were prevalent in the region before land reforms took place and people could claim what was rightfully theirs.

The development policy in India, and in extension, in Jammu and Kashmir, is based on the premise of utilitarianism (Ramanathan, 1996). The utilitarian approach embodies the principle that advocates the greatest happiness to the greatest number in society (Mill, 1901). This greatest good implicitly provides for the sacrificing of rights and entitlements of some towards the larger collective benefit of society and of the nation by extension.

This utilitarianism also forms the basis of what in modern times is known as public purpose or public interest (Ramanathan, 1996). Within the Indian development story, public purpose has become the engine of the technocratic development model that seeks to tame and subject nature and society to administrative order and planning. This public purpose has found legal sanction in the form of laws right from the time of British rule and continues to be part of post-independence Indian jurisprudence, embodied in land acquisition law.

However, the much-invoked public purpose has no delimited definition. Instead, it is left to the relevant authority, legislative and executive, to declare what amounts to a public purpose. The state often acquires land for different development projects in the name of economic progress, exploiting the broad and vague idea of public purpose (Chakravorty, 2013).

Hence, the category of public purpose essentially confers a legal and moral legitimacy to the acquisition of land by the State, which more often happens to be involuntary acquisition (Roy 2019, p. 25).

This authority to acquire land for public purpose falls under the eminent domain powers of the State, which the State has conferred upon itself in order to advance the interests of the ‘people’ towards the greater good of society and the nation. This idea of utilitarianism, or the more well-known term, public purpose, has faced criticism on the grounds of being inattentive to the costs which more often surpass the benefits that the affected community enjoys (Ramanathan, 1996; Mohanty, 2005). This essay analyses these costs and the forms in which they are borne by the people who do not share the benefits of the development projects for which they are made to suffer in the name of the greater good.

These development plans spell doom for the people who inhibit the land acquired for development projects; dispossession and displacement are intertwined with the process. So are the environmental impacts that hardly garner the attention of developmental planners. The environment, too, is seen as collateral damage in the pursuit of the greater good that development is expected to deliver. This essay builds on the data regarding the two hydropower projects mentioned above to establish the utilitarian nature of hydropower projects in Jammu and Kashmir.

It argues that the high modernist approach (Scott, 1998) pursued in these projects is a threat to the survival of the local indigenous population and violates their right to a dignified life by altering the environment irreversibly and exposing the inhabitants of the region to natural disasters. While provisions for payment of compensation to the affected families for dispossession of land is part of the legal mechanism, critical development scholars have questioned the reasonableness and fairness of such payments to serve any justice to the families (Mathur, 2009; Mohanty, 2005; Ramanathan, 1996).

They have argued that the money paid, at best, serves as a facade of equity and fairness and performs the task of covering up the inherently exploitative processes of development.

Nonetheless, contrary to this critique, there are arguments which assert that these procedural issues can be identified and addressed, and that the alleged discriminatory nature of development planning can be minimised. However, despite changes in the law where processes of development planning have been made more democratic and participatory in principle, their implementation remains farfetched because of the deep-rooted differential power dynamics that operate during these processes (Roy, 2019).

Gupta (2012) poses a fundamental question on the appropriateness of the very power of ‘eminent domain’ ‘as an institution in democratic society’ that facilitates land acquisition and asks: Can an institution crafted specifically to take resources and land from subjects for the benefit of the Crown and its corporate associates ever be modified to serve a public purpose? I argue that, given the historical development of eminent domain in India, the answer is ‘no’ (Gupta 2012, p. 451).

It is important to note that there are structural factors at play, such as the pro-project bias of people in positions of power, the lack of responsibility towards the affected community, and expectations of certain outcomes irrespective of any consideration towards the detrimental consequences they may have, which dominate development planning.

To go beyond the question of social justice that utilitarianism is in direct conflict with, this analysis further traces how these development projects are not merely violative of the rights of people but also have larger political purposes to fulfil. In order to illustrate this, this study uses the concept of ‘instrument effects’ by Ferguson (1994), which helps us to ask questions beyond the failure and adverse impacts of development projects. The concept of ‘instrument effects’ helps us analyse the non-economic functions that development projects serve.

Hydropower projects represent not merely the technocratic pursuit of economic growth (Khagram, 2004, p. 4), but also serve the symbolic function of the conquest of nature and the becoming of a modern State (Klingensmith 2007, p. 2).

Right from the achievement of independence in India, hydropower projects have been promoted as acting towards nation-building (Roy, 2019). It is this political function that dominates the planning processes at places such as the disputed territory of Jammu and Kashmir.

This excerpt from Farhana Lateif’s essay in ‘Living with the Weather: Climate Change, Ecology and Displacement in South Asia’, edited by Piya Srinivasan, has been publish with permission from Yoda Press.

This excerpt from Farhana Lateif’s essay in ‘Living with the Weather: Climate Change, Ecology and Displacement in South Asia’, edited by Piya Srinivasan, has been publish with permission from Yoda Press.