The COP28, like all the previous climate summits, has convened to address the pressing issues stemming from climate change and global warming. Taking place in the UAE, the summit has brought to the forefront the complex interplay between mitigating climate change and fostering responsible economic development. This involves increased production and sustainable consumption, with an emphasis on transitioning from fossil fuels to alternative energy sources such as solar, wind, and nuclear power plants.

Ironically, the presiding figure at COP28 is Sultan al-Jaber, chief executive of one of the world’s largest fossil fuel-producing companies based in the UAE. This raises intriguing questions about the challenges of reconciling economic interests with environmental responsibilities, especially as the company plans to increase production, which will potentially result in more greenhouse gas emissions. Notably, this dynamic has sparked a fierce campaign, especially by the European Union (EU), to completely phase out fossil fuels. In contrast, the COP28 President favours a slowdown in production instead of a total phase-out. After all, why would he become party to a proposal that could shut his business down?

A landmark decision at COP28 revolves around the long-standing and contentious issue of the ‘Loss & Damage Fund’, which aims to bail out countries affected by policy formulations adopted by developing and Least Developed Countries (LDC) for climate change damage mitigation. While the agreement is a welcome step, concerns arise about the distribution of funds. The major contributors—such as the US, UK, EU, India, and China—may contribute varying amounts based on their expendable funds. Ideally, an equal contribution from all participating countries could be considered, like it was done in the case of the New Development Bank, where all BRICS members chip in with the same amount.

Another issue with the Loss & Damage Fund is regarding its administration—the fact that the International Monetary Fund (IMF) is made in charge of overseeing it raises serious concerns about neutrality. COP28 could have explored a rotational administration model, with a team of administrators changing every few years. Additionally, COP28 should have instituted a robust review and audit mechanism for projects and compensation disbursement, which would have added transparency and accountability to the fund’s operations.

The term ‘compensation’ itself is not sufficiently defined within the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). It encompasses economic and non-economically quantifiable components, including the loss of family, community, and emotional well-being, as highlighted in the 2022 report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Also read: US & other nations will push for tripling nuclear power by 2050 during COP28. India must join in

India is showing the way

While India is part of all the major global initiatives to address global warming, it grapples with the dual challenge of participating in international efforts while sustaining domestic poverty alleviation programmes and improving manufacturing to foster economic growth. India, with more than 17% of the global population, has contributed only about 4% of the global cumulative greenhouse gas emissions between 1850 and 2019. India missed the first and second industrial revolution due to colonial rule, and the first 50-odd years after Independence went towards strengthening agriculture and building basic industrial and energy infrastructure. This is one reason why India’s per capita annual emissions are about a third of the global average. With the advent of coal-fired power plants and large-scale industrialisation, emissions assumed larger proportions and needed immediate actionable plans.

To meet its commitment as a responsible global actor, India has pledged a 45 per cent reduction in EPU emission intensity (Emission Per Unit of GDP from 2005 levels) and a transition to renewable sources for 50 per cent its electricity generation. Additionally, India has committed to creating about three billion tonnes of additional carbon sink through afforestation. Initiatives like the One Sun, One World, One Grid (OSOWOG) project and establishment of the International Solar Alliance in 2015 showcase India’s dedication to achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) by 2030.

Recognising the importance of grassroots initiatives, both the Union government and state governments should focus on establishing low-carbon rural industrial bases. These bases should prioritise minimal emissions and maximum use of human capital, local resources, and non-energy-consuming technology. Rather than the governments heavily investing in smart cities, which have become biggest contributors to climate change, there should be a concerted effort in Higher Education Institutions (HEI) and industrial research units toward rural development and the creation of “smart villages” .

Beyond the reduction of emissions, a critical aspect is the development of technologies for optimal trapping of emissions in both particle and gaseous forms. Currently, there is a serious gap in research on these technologies. Only the government can set up a well-funded agency that can come up with a technological solution that involves contributions from smelting and other high-energy-consuming industries. Emissions, including hydrogen, could serve as potential alternative sources of energy. Thorium-based fast breeder reactors are another area that needs greater research and faster results.

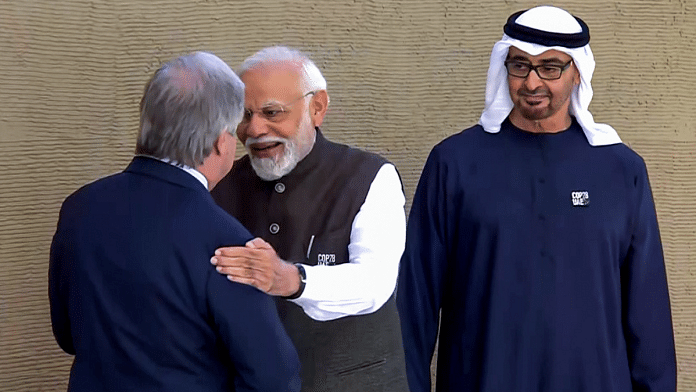

During the recent G20 summit, Prime Minister Narendra Modi unveiled the Life Style for the Environment (LiFE) master plan, which was first introduced at COP26 in Glasgow in 2021. The PM called upon the global community to adopt LiFE as an international mass movement towards “mindful and deliberate utilisation, instead of mindless and destructive consumption” to protect and preserve the environment.

India strongly believes that it is the individual and collective duty of everyone to lead lives in harmony with the Earth. PM Modi even suggested that those who practice such a lifestyle could be recognised as “Pro Planet People” under LiFE. This idea was reiterated as the template for G20 as “One World, One Family, One Future”. Unless the climate change summit recognises and respects such a global view, achieving universal solutions and consensus will be difficult.

Seshadri Chari is the former editor of ‘Organiser’. He tweets @seshadrichari. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant)