In the 1960s, many of these smaller sub-castes residing in the more backward regions of the state were not part of the RPI and it disappeared before it could mobilize them. By the 2000s, many were entering the mainstream and experiencing a process of modernization with each sub-caste discovering its own history, heroes, culture and distinct identity. This is the reason why the social and cultural distance that had always existed between them and the Jatavs had widened considerably, leading to each attempting to chart its own social and political journey. Ambivalence and accommodation, once again, as in the period of Congress dominance, characterize the relationship between the smaller Dalits and the BJP. There are, as our study has shown, strong protests against atrocities upon Dalits but preference for the BJP while voting. However, the current phase is more challenging, with large sections of the Dalits being included culturally into the saffron fold, suggesting that it is not just a tactical step, but a move towards ideological conversion.

Our narrative has highlighted that in terms of ideology, the Dalit movement has been divided into Ambedkarites or proBSP and Hindutvawadis or pro-BJP, though these divisions intersect each other in more complex ways in politics. The Hindutvawadi Dalits, for example, have embraced the legacy of Ravidas, a Bhakti era religious figure, while the Ambedkarites view Ambedkar as the inheritor of the legacy of the Buddha. The fragmentation in the 2000s is greater as, unlike in the period of Congress dominance, it is not only political, that is, it is not just an attempt to gain the support of Dalits to win elections and become a dominant ruling party. Importantly, it is also cultural, as the BJP has endeavoured to bring Dalits into the larger Hindu fold, rendering the Muslim as the common ‘other’. By looking after their cultural needs and desires, by showing respect to their distinct culture and identity, and by initiating new welfare strategies, the BJP and the RSS have conveyed that Dalits will be an important part of the Hindutva discourse. Thus, political, social and cultural strategies have been deftly combined to create a broad spectrum of the Hindu support base. This ideological conversion is not merely top-down, but permeates society as a whole today. Due to the cultural mobilization of the BJP–RSS, there is greater acceptance of the idea of a Hindutva among large sections of the population, including the Dalits and backward castes.

Moreover, the agenda of social justice, which the BSP under the leadership of Kanshi Ram propagated as its core ideology, has lost much of its importance for the party. Arguably it could be attributed to Dalits aspiring for and moving towards greater material advancement in the 2000s, as well as Mayawati’s strategy in 2007 of helping the sarva samaj. It is also due to the new politics of recognition and redistribution that the BJP has made the bedrock of its ideology of subaltern Hindutva. The smaller Dalit sub-castes today have earned recognition for their distinct culture, identity and history, and as labhartis they receive welfare measures to satisfy their basic material needs from the BJP, something that they argue was not provided to them by the BSP. Yet, it is undeniable that the idea of social justice—of helping the disadvantaged and poor—is a contribution of the BSP. It will remain a significant ideological legacy of the BSP to transformative democratic politics, which no party can ignore.

Nowhere is the unravelling of the BSP more evident than in the sub-regional disintegration of the Dalit movement in UP since the rise of the BJP. Divisions within the Dalit movement along sub-regional lines have historically been a feature in the state, both due to UP’s large size and the existence of different cultural regions. In recent years it has taken two forms: the emergence of new, separate Dalit organizations, and rising differentiation between the smaller sub-castes residing in different sub-regions of UP. The former has been the work of a younger generation unhappy with Mayawati’s failure to deal with increasing atrocities by the upper and middle castes, confront the BJP, her lacklustre campaigns in recent years and the consequent rapid downward spiral of the BSP. New organizations have been formed by both the Ambedkarites and the Hindutvawadi Dalits, as well as by different sub-castes, though the large majority is by Jatavs, many of whom are former members of the BSP. These organizations reflect Dalit assertion on the ground and are popular among the younger generation. However, they are yet to build organizational strength and mobilize beyond their limited areas; they also lack the resources to fight elections. Mayawati has not shown a desire to join hands with them to strengthen the BSP. Nor are they willing to join hands with each other to fight the BJP, as each organization would like to replace the BSP on its own and emerge as a strong Dalit party. Thus, at present they lack the capacity to build a strong pan-UP Dalit movement or party.

Also read: UP Dalits’ attitude to bloc voting different from Tamil Nadu. Research tells us why

A second aspect of fragmentation is the emerging social and political divisions between smaller sub-castes residing in different sub-regions of UP, who are rediscovering their own specific sub-regional and cultural identities. Much literature exists which has mapped the shifting terrain of the political choices of the numerically weaker Dalit castes, like the Balmikis in western UP, the Pasis in the Awadh region and the Khatiks in Purvanchal. During the phase of consolidation of Dalit identity in the 1980s, these sub-castes shifted from the Congress to the BSP. However, by the late 1990s, disillusioned with the BSP, they began to respond to the outreach of the non-BSP parties— the SP, the Congress and, subsequently, the BJP.

A common feature that has fuelled this shift is disillusionment with the Jatav-centric politics of the BSP. The Balmiki community’s consistent mobilization behind the BJP and Hindutva discourse in western UP is a classic case of how the BJP has been able to fulfil both their material and cultural aspirations. Their electoral and political trajectory in the last decade shows that the community has not responded to overtures by non-BJP parties. In our longitudinal fieldwork in 2015, 2017, 2019 and 2022 in Balmiki localities in western UP, we found the community fully integrated into the saffron discourse. Materially, they felt let down and left out by the BSP and the SP in the 1990s and early 2000s vis-à-vis the Jatavs and Yadavs, respectively. Culturally, they feel they have been shown respect through consistent outreach and positive resonance by the Hindutva outfit.

Similarly, in the Avadh region, while the Pasi Dalits supported the BSP until 2012, they shifted to the SP in the 2012 assembly election. In our field study, conducted between December 2012 and January 2013 in the aftermath of defeat of the BSP and the victory of the SP, the Pasi respondents communicated the sense of being left out and harassed by the police under BSP rule on the charge of manufacturing illicit liquor during 2007–12. They shifted to the BJP in 2014 and since then have been supporting the party. But in the 2022 assembly election, a section of them shifted away and supported the SP, inflation and unemployment being the major reasons for this.

While the Khatiks view the SP and BSP as being exclusionary and catering solely to the Jatavs, Yadavs and Muslims, the shift of this community in the Purvanchal region towards the BJP has taken a different route.31 The Khatiks alleged that the communal riots during the rule of the SP saw the latter favouring Muslims against them in Mau, Azamgarh and Gorakhpur, among other districts. They also asserted that it was the Hindu Yuva Vahini and other saffron outfits that came to their support. Hence, the community developed an affinity for the Hindutva discourse. Though a majority in the community voted for the BJP in the 2022 assembly election, we found in our fieldwork that a section among them was angry with the saffron party due to issues of inflation and unemployment, which have affected them.

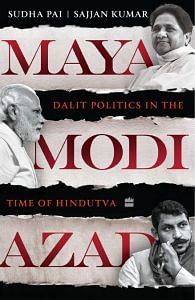

This excerpt from Sudha Pai and Sajjan Kumar’s Maya Modi Azad has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.

This excerpt from Sudha Pai and Sajjan Kumar’s Maya Modi Azad has been published with permission from HarperCollins India.