In 2009, Xi Jinping came out of his shell in a rare moment of truth and revealed to all the new-found national pride permeating the Party’s leadership.

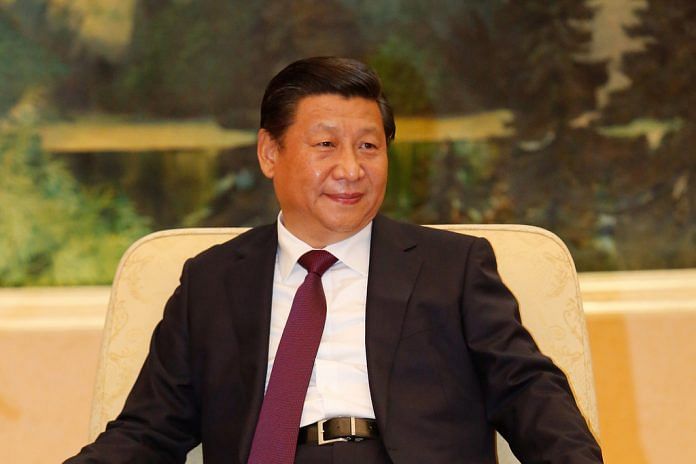

There was once a rare moment of truth when Xi Jinping, usually so in control of his public persona, came out of his shell. Particularly, he emerged from the shell of cunning cautiousness that generally characterises speeches given abroad by leaders of the Chinese Communist Party. Xi was in Mexico, the ‘backyard’ of China’s great American rival. In February 2009, he was already one of the favourites for the leadership, but was still only vice-president. He was shoring up his international standing with multiple trips abroad.

Standing confidently behind the microphone in front of the Chinese embassy in Mexico, he faced a specially-selected audience of compatriots — expats, diplomats, businessmen and students. The peaceful atmosphere made his remarks all the more striking: ‘There are certain well-fed foreigners who have nothing better to do than point the finger,’ Xi declared. ‘Yet, firstly, China is not exporting revolution, secondly, we are not the ones exporting poverty or famine either, thirdly, we do not cause problems in other people’s countries. What more can I say?’

It went without saying that those who did export famine and unrest were obviously the Americans. For the deputy chief of mission at the US Embassy in Mexico, there could be no mistaking this, as he pointed out in a diplomatic telegram, describing Xi’s ‘unusual behaviour’, ‘which contrasts strongly with the theme of global cooperation’ promoted at the start of his visit ‘to a country with strong ties to the United States’.

China is particularly resentful of being a target for Western criticism when it deems its American rival to be a much more questionable world superpower. Xi’s declaration was manifesting real annoyance. It is usually his won’t, when abroad, to evoke the pacific rise of his country and ‘win-win’ agreements. This sudden rage revealed to all the new-found national pride permeating the Party’s leadership and clamouring to be heard: China, now endowed with a strong economy and army, no longer needed lessons from anyone. Beware, it said: China has become touchy.

The 1990s were probably the tipping point when a well-studied modesty gave way to demonstrations of national pride. In 1996, an overtly nationalist book, China Can Say No, became a bestseller. Written by five young intellectuals, the book accuses the United States of hindering China’s growth and wanting to ‘contain’ it as Washington had done with the Soviet Union during the Cold War.

In 2009, some of these authors struck again with another work, Unhappy China, asserting that the country must adopt a hegemonic position in the world from which to oppose Western influence. The time had come to take a leading international role. Far from pulling back, what was needed was an expansion of influence.

In a blend of cultural patriotism and political messianism, one of the book’s authors, Huang Jisu, explained to a Chinese newspaper: “If it wants to feature among the leaders of the world, China must absolutely equip itself with superior assets … It must not lose the achievement of five thousand years of history. We need to reclaim a large part of what we have shunned … Not only must China save itself, but it must also save humanity … The Chinese people must shoulder this task, no matter how heavy.”

The fenqing (‘angry youth’) ensured the book was a success — the term describes young nationalists, urban dwellers active on social media and the wider internet, who know how to make themselves heard in the public arena and are looked upon favourably by the government. One year earlier at the time of the Beijing Olympics, and under the indulgent eye of the government, they had launched the campaign to boycott the French supermarket chain Carrefour, following the incidents that had affected the Olympic torch relay in Paris. One month later, they had spontaneously gone to Sichuan province to take part in rescue operations after a violent earthquake in which more than 70,000 had died.

At that time, I joined a small group of students in the mountains near Chengdu. Over the course of the day, they gradually and symptomatically revealed themselves to be critical of the fact that I was a French journalist. One gave me a straight-faced warning, inspired by the Liverpool anthem: ‘We’ll never walk alone’. We, he told me, are a force to be reckoned with; we are to be feared and we know it.

It was on this surge of national pride that Xi rode as soon as he came to power. He would flatter these young nationalists on the one hand, and on the other would reach out to the proponents of 1980s neo-authoritarianism, who were persuaded that only a strong regime had been able to save the country after the repression of the Tiananmen movement. Gone were the days when, following the 1989 massacre, China had been marginalised by other nations and Deng advised ‘keeping a low profile and biding our time’ (taoguang yanghui, ‘hide from brightness and nourish obscurity’). This counsel of reserve summarised the strategy Deng had formulated in twenty-eight characters in an address to future generations: ‘Observe calmly; secure our position; cope with affairs calmly; hide our capacities and bide our time; be good at maintaining a low profile; and never claim leadership’.

Xi has broken with this low-profile doctrine, giving encouragement to young and not-so-young generations of nationalists — even, as we have seen, if this means reviving the old enmity with Japan. Even if it involves explicitly identifying the United States as the great twenty-first-century enemy, always presented as being determined to weaken China. With conspiracy theory lending a hand, this version of reality has found many takers.

In 2013, a documentary produced by the People’s Liberation Army, entitled Silent Contest, caused a great stir. It argued that, since the fall of the Soviet Union, Beijing had become the Americans’ enemy number one. To achieve its ends, the United States had embarked on an ‘ideological war’, much more efficient than a traditional war.

As Li Zhiye, president of the China Institute of Contemporary International Relations, explained in the film: ‘Since the Vietnam war, the US has more often chosen the strategy of “winning without a war.” This is a soft war using politics, economics, ideas, and culture as weapons with its advantageous military power as backing’.

Silent Contest generally develops the same ideas as Document 9: that the Americans support NGOs who seek to overthrow the Party, and seek to bribe Chinese soldiers or influence Chinese young people with their ‘vulgar’ culture, using social media and other online platforms. Much as the Arab uprisings would be treated two years later, the unrest in Iran in 2009 is given as an example of the Americans’ capacity to influence the young. The film was banned a few weeks after its release, and there is no way of knowing if the reason was the nature of its content, perhaps deemed to be overly explicit.

It is against this American soft power that the nationalist discourse calls for China to fight, with varying degrees of prudence. Nevertheless, this does not mean that Xi has neglected the classic military route. His predecessors had already embarked on the modernisation of the army and increased the military’s budget, the second largest in the world after the United States. Xi went even further, using the fight against corruption to launch sweeping reform. It was the perfect excuse to make some heads roll and appoint his own men.

Xi prides himself on his military knowledge. He readily draws attention to the fact that, in the early 1980s, he was the personal assistant (mishu) of the then minister of national defence, Geng Biao. In 2016, Xi suddenly gave himself a new title, that of Commander-in-Chief. He is now in charge of everyday operations in case of external conflicts or regional tensions.

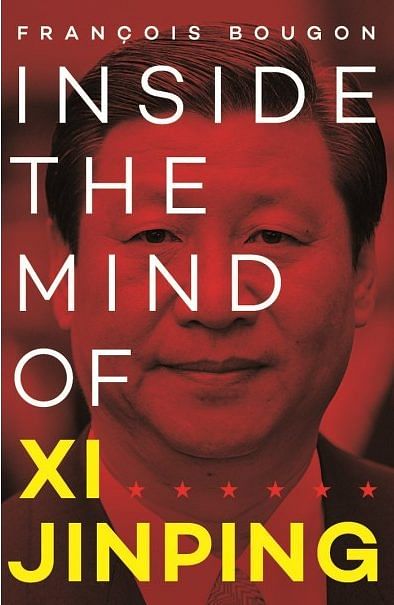

This excerpt from ‘Inside the Mind of Xi Jinping’ by Francois Bougon has been published with due permission from Context, an imprint of Westland Publications.

This excerpt from ‘Inside the Mind of Xi Jinping’ by Francois Bougon has been published with due permission from Context, an imprint of Westland Publications.