When Juggernaut commissioned me to write a biography of former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee, I was initially unsure, even reluctant. Would I, a professed liberal who has a visceral disagreement with politics based on religion, be too put-off by Vajpayee’s RSS-shaped worldview to tackle the subject properly? Today, under the Narendra Modi-led BJP dispensation, when India is hyper polarised, would I be “selling out” by writing on the first BJP prime minister?

Ironically, as I delved deep into Vajpayee’s life and thoughts, I found that my liberal viewpoint was actually my strength in coming to grips with the man. I came to my subject as a sceptic, devoid of adulation and had to work much harder at understanding him than I had to with Indira Gandhi, the subject of my first biography. Yet I found myself drawn to his charming, humorous persona, even as I was repelled by the communal politics he regularly played.

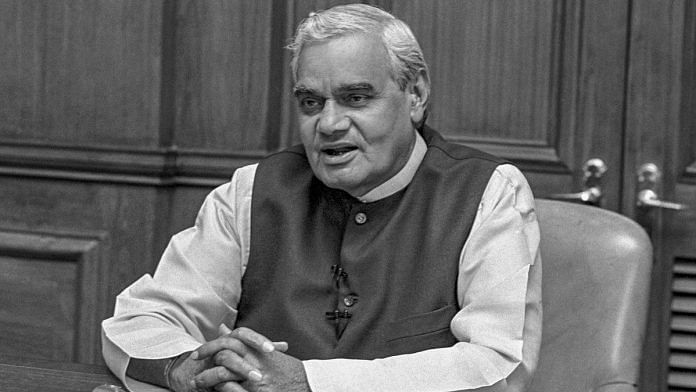

The real Vajpayee

The Vajpayee I discovered was a contradictory, clever, strategic, ambitious and calculating politician armed with great self-belief. He always seemed convinced that he, his father’s favourite son, was destined for big things, and was quick to sense where his political advantage lay.

My explorations led me to a complex portrait: of someone mentored by MS Golwalkar, the Hindu supremacist RSS chief and by Syama Prasad Mookerji, the Jana Sangh founder; someone who was also a fervent admirer of Jawaharlal Nehru, counted aristocratic Communists like Oxford-educated Hiren Mukherjee as his friends, and engaged in a lifelong tug of war with the RSS. Vajpayee believed in the core Hindu nationalist cause, but he also believed passionately in modern parliamentary democracy and all his life struggled, sometimes fruitlessly sometimes successfully, to be a model of both.

His politics, too, was fundamentally shaped by the bludgeoning dominance of the Congress in the first two decades after Independence: in his desperation to challenge this Nehru-Gandhi led leviathan, he would do almost anything, even play with communal fire.

Also read: When Advani and Vajpayee founded BJP, they knew RSS needed to be kept at arm’s length

A parliamentarian unlike Modi

I began writing the book in 2019, and inevitably Narendra Modi loomed large. For anyone wanting to write about Vajpayee today, Modi is the elephant in the room, and it’s natural to compare the two BJP prime ministers. I was able to clearly see what a sharp and dramatic contrast there is between the two. Vajpayee may have normalised and legitimised saffron politics, but he was no centralising autocrat or a one-man show like Modi.

The first BJP prime minister was above all, a diehard parliamentarian. He grew up in politics in the 1950s and 1960s – the golden age of India’s Parliament – and parliamentary norms and practices entered his bloodstream from the day he set foot in the House.

He was Vajpayee of the Lok Sabha (and occasionally of the Rajya Sabha), such a regular parliamentary fixture that his bureaucrats would complain that the PM was always sitting in the House, even listening to private members’ bills.

This is why, as Vajpayee’s liberal biographer, I was not interested in lauding Vajpayee’s ‘nationalist’ nuclear tests or focussing on his economic liberalisation. Instead, I wrestled with the question of how a constitutional democrat like Vajpayee could also cynically use the Ram Mandir movement to catapult himself and his party to power.

In the Modi era, by stark contrast, we are seeing a tragic degradation of Parliament. There is virtually no reach out to the opposition, and repeated adjournments and disruptions. It would have been unthinkable for Vajpayee to ram through highly contentious legislations like doing away with Article 370 or pushing the Citizenship (Amendment) Act and the farm laws without debate in Parliament.

Today Vajpayee’s party calls for an “opposition-mukt Bharat” or annihilation of the opposition. An opposition man all his life, Vajpayee would have been incapable of such name-calling. His close colleague in government was the socialist and former union leader George Fernandes, who would probably be designated as an ‘anti-national’ today. Vajpayee did not shut the opposition up, and instead reached out constantly to them even when he was publicly attacked by his own RSS colleagues like Dattopant Thengadi and KS Sudarshan.

I was struck, too, by how Vajpayee’s modus operandi was completely different from Prime Minister Modi. Unlike Modi, Vajpayee was a collegiate team player, conceding autonomy to a phalanx of high-profile ministers, each with strong personalities of their own. He brought in economic reforms through a dogged pursuit of reconciliation and consensus-building.

Nor was he intolerant of criticism. He sat through trenchant attacks on him in the House: in 1970 Indira Gandhi openly accused him of “naked fascism”. In 1996, the CPI’s Indrajit Gupta called him “fake”. Vajpayee accepted the fall of his government by a single vote in April 1999, a defeat that the Modi-led BJP might today regard as quaint.

Also read: What is Modi-Shah BJP’s ideology? You’re wrong if you say Right wing, because it’s Hindu Left

What the liberal biographer sees

A liberal biographer can also see what a saffron sympathiser may not: just how much Vajpayee admired the Nehru-Gandhis. Unlike Modi, Vajpayee was no ‘bharatiya’ cultural warrior against the so-called ‘Lutyens’ elite’. Vajpayee himself was very much a Delhi insider, and in fact an occupant of Lutyens’ bungalows all his political life. He was awestruck by India’s political dynasties, from the Nehru-Gandhis to the Scindias.

He hero-worshipped Jawaharlal Nehru, quoting Nehru repeatedly and, when he became foreign minister, insisting that Nehru’s portrait be placed back on the foreign ministry wall. When I described him as the ‘Swadeshi Nehru’ in an Outlookcover story I co-wrote in 1998, I remember he was most pleased.

Then there is Vajpayee’s love of alcohol, non-vegetarian food, or of the company of attractive women artistes – none of which may have been palatable to the Sangh Parivar. For the liberal biographer, however, Vajpayee’s sensual love of pleasure and maverick personal life reveal an unconventional even bohemian character, at severe odds with the puritanical Sangh Parivar. There is no evidence to show that Vajpayee even performed a daily puja in his home. The founder of the BJP was more liberal and westernised than he was an orthodox or pious Hindu.

As Vajpayee’s liberal biographer I can also see how often Vajpayee failed the test of constitutional democracy. He failed in 1992 when he delivered a communal speech on the eve of the demolition of the Babri Masjid. He failed in 2002 when he did not act against a Gujarat administration accused of complicity in riots. He made an incendiary speech in Assam in 1983, and during the Bhiwandi riots in 1970, he bellowed provocatively: “Ab Hindu maar nahin khayega.” (The Hindu will no longer be beaten).

But the opposite is also true: when in government, he journeyed to Pakistan in 1999 in a bus vowing never to declare war, and in 2003, delivered a speech in chaste Urdu in Srinagar promising to bring “insaniyat” to Kashmir.

For all these reasons, Sangh Parivar hardliners attack Vajpayee for being a “half Congressman,” for failing to ever take the BJP over the 200-seat mark, for soft-pedalling on Ram Mandir. Left hardliners attack him for being a bigot wearing an acceptable mask.

Both miss what the liberal biographer sees: Vajpayee was a man waging a battle to push the Hindu nationalist genie into the bottle of parliamentary democracy. He was flawed, weak in many ways, and played cynical politics, but he never stopped trying to reconcile diverse groups and opening dialogue with his adversaries.

As I completed the final draft of the book, I realised that an important liberal principle was reflected in Vajpayee’s life—the ability to form friendships even with those who we don’t agree with. Perhaps his many faceted, contradictory personality opened himself up to people of all kinds. That’s why today’s India, trapped in rival echo chambers, needs to read the story of Atal Bihari Vajpayee.

Sagarika Ghose is a journalist, columnist and author. Her recent published works are: “Indira, India’s Most Powerful Prime Minister” (Juggernaut) and “Why I Am A Liberal.” (Penguin Random House). Views are personal.

(Edited by Neera Majumdar)