Nine Hours to Rama reflects our complicated relationship with censorship.

Fifty-seven years after India banned the book Nine Hours to Rama, a fictional account on Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination by Hindu extremist Nathuram Godse, as well as the film based on it, the story of its censorship remains relevant.

Then government and its ordinary citizens’ differing attitudes towards Nine Hours to Rama reflect our complicated relationship with censorship—which exists to this day.

‘A rather poor book’

The book and the film are known for being banned in Nehruvian India. They were banned separately and not simultaneously. The novel, written by a historian Stanley Wolpert, used Mahatma Gandhi’s murder as the central plot.

Barring Gandhi, his killer Nathuram Godse and Godse’s accomplice Apte, all other character names were fictitious. It attempted to imagine circumstances of Godse’s life from the beginning that supposedly pushed him towards such a violent act. It also indicated probable neglect by the Indian government in saving the Mahatma.

Also read: Mahatma Gandhi hated movies, but watched 2 in his lifetime

The Indian government banned the book months after it was published in London. (Novel Banned, TOI, Sep.7 1962, p.5) Further clarification on the next day said the book ban also implied ‘possession, purchase and sales of copies of the book already imported under a ban.’

According to the report, ‘official sources were unable to throw light on why the book had been banned’ but it was mentioned that it portrayed Godse ‘in wrong perspective and that some portions were liable to be hurt the feelings of various sections.’ (‘Ban Applies To Possession Too, TOI, Sep. 8, 1962, p.9)

A column in the same edition of the newspaper termed the ban ‘a meaningless action’, noting that most reviews ‘dismissed it as a rather poor book.’ But the customs ban generated some curiosity. ‘It is difficult to understand how national honour was ever lost by publication of the book or has been regained by its banning,’ remarked the column and termed the step the reflection of ‘an exaggerated national ego and a degree of political immaturity.’(Current Topics, TOI, Sep. 8, 1962, p.6)

Stanley Wolpert expressed ‘shock and distress’, ‘sorrow and surprise’. Arguing for freedom of speech and press, he reminded that founding fathers and leaders of both America and India ‘shared that same passionate faith in freedom and repugnance of tyranny.’ He wanted the government to let people read the book and decide. ‘If it is a poor job of fictional writing, it will banish itself.’ He also reminded India its motto Satyamev Jayate (truth alone triumphs) and regretted that those words sounded hollow in light of the ban. (Ban On a Novel, TOI, Oct 7, 1962 p.6)

Also read: The two family members of Mahatma Gandhi who dared to disagree with him

A reader from Bombay retorted that the book was banned ‘exactly for the reason the motto expounds—because it distorts truth.’ (Ban On a Novel, Mrs. Daya Patwardhan, TOI, Oct 14, 1962 p.8)

Years after the ban, Wolpert said in an interview to journalist Ashok Malik, that his first book Nine Hours To Rama was closest to his heart and he couldn’t understand the reasons for its ban. ‘May be I came too close to the truth in describing prevalent sentiments.’ (I’d Loved to Meet Gandhi and the Buddha, TOI, Sep 8. 1996, p.11)

Nine Hours to Rama: ‘A mistakenly made film’

Hollywood director Mark Robson purchased the rights of the book when even the manuscript was not ready and the last chapter was yet to be finalised. It was earlier named ‘Day of Darkness’ but was changed later to become Nine Hours to Rama. By the time book was banned in India, Robson had already obtained permissions from the Indian government on the basis of 50 pages of script and completed shooting on Indian locations. (Last Nine Hours of Gandhiji, P. G. Krishnayya, TOI, Oct 28 1962, p.10)

Outdoor scenes for the film were shot in Delhi, Bombay, Pune and Nashik. It involved well known Indian actors David and Achla Sachdev. The lyricist of Achhut Kanya (1936), Jamuna Swaroop Kashyap (spelt as Casshyap in the film) was chosen for Gandhi’s role because of physical resemblance.

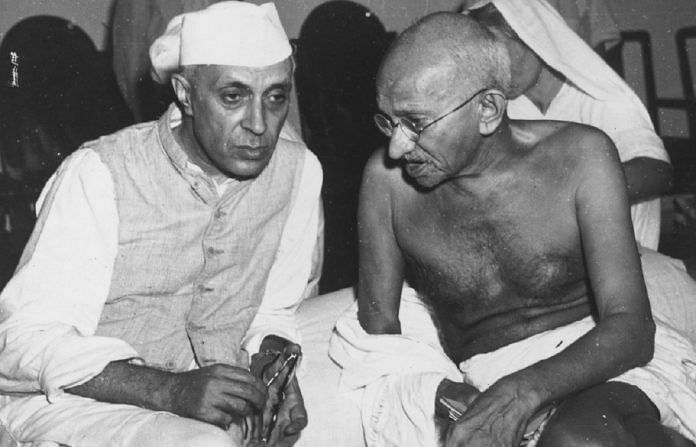

The film Nine Hours to Rama portrayed the fictional account of Godse’s activities in the last nine hours of Gandhi’s life, with liberal use of flashbacks. It could well be called the ‘fictional biopic’ of Godse—he was even shown boozing and going to a sex worker few hours before the murder to hide safely. As the film’s producers submitted it to the Censor Board, the I&B minister invited then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and other ministers ‘to see the film and advise him whether the Government should allow its exhibition.’ (Ministers See Film On Gandhiji, TOI, Jan 3 1963 p.1)

The report said then President Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan had seen it the previous day.

Prime Minister Nehru, replying to a question in Rajya Sabha, justified the decision to the ban the film. He said he was sure ‘the makers were not aiming to defame Gandhiji or anything in India. But Gandhiji comes very little in the film itself and the person who is supposed to represent Gandhiji lacks all dignity.’

Also read: The reason why Gandhi wanted to go to Pakistan

He called the film ‘mistakenly made.’(Deviations From Script In Film On Gandhiji, TOI, Feb 28, 1963, p.5)

The I&B Minister B. Gopala Reddy clarified that the script of the film had been seen by the government but there were various deviations from it when the film was shot.

A reader from Bombay, however, did not buy the minister’s claim. Deviation or no deviation, she argued, a film based on ‘a sex-ridden, fictionalised account’ in which ‘Gandhiji appears exactly in the last three pages of the 270-page book’ can’t do justice to dignity of Gandhiji.

(Nine Hours To Rama, P.K.Ravindranath, TOI, Mar.17, 1963, p.8)

Thanks to the internet, the ban on the book and the film remains irrelevant today, but the culture of banning has only worsened.

Urvish Kothari is a senior columnist and writer in Ahmedabad.

How can i get “Nine Hours To Rama” book ?

A piece or jewel from the History. Nehruites prefer to forget conveniently that the first amendment to the Constitution was on account of the failure of the Nehru Government to curb dissent ( Thapar magazine case). Secondly, in 1952, he got Rajaji, not a member of any house in the erstwhile Madras State, as the chief minister though the Communist Party of India was the single largest party. Rajaji did not contest any election for any house but was nominated. A dubious distinction. Thirdly, in 1952, he promulgated Governor Rule in Punjab as the Congress Chief Minister Dr Gopi Chand Bhargava refused to resign as he was enjoying majority among the Congress legislators. After a few months, Bhim Sain Sacchar, a protege of Nehru was installed as CM. Justice Rajinder Sacchar and Kuldip Nayar, son and son-in-law of Bhim Sain Sacchar never wrote on this sensitive misuse of the democracy. Fourthly, in 1958, the dismissal of the EMS Communist Govt, the first elect Communist Government in the world, is well known.