With the resumption of the Israeli war on Hamas and the Ukraine war showing little sign of ending anytime soon, the United States’s international commitments are showing no signs of abatement. A good question that countries in the Indo-Pacific should ask is what this potentially means for stability in the region, particularly concerning any potential Chinese adventurism. Would the US be able to handle these multiple crises and continue to deter China or could Beijing see an opportunity and act on it?

It is understandable that as a global power, the US has commitments in multiple regions. Many prominent analysts such as Elbridge Colby argue that the US should prioritise China and Taiwan over others such as Ukraine.

China is facing domestic troubles too, which might stay its hand. At least this is what Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen seems to think: In a recent interview with The New York Times, she argued that China’s leadership is too “overwhelmed” with domestic troubles to consider invading Taiwan. But this can’t be considered as a serious assessment. One can only hope that the Taiwanese President’s views do not reflect the country’s strategic planning because it is always foolish to assume such best-case scenarios about your adversary. Israel, to mention only one example, appears to have dismissed intelligence about a Hamas attack with such magical thinking. Closer home, one of former Indian Prime Jawaharlal Nehru’s greatest mistakes, which formed the basis of India’s military plans, was assuming that China would not attack in 1962.

However, it might also be alarmist to assume that China will see the US’ current preoccupation as an opportunity to advance itself in the Indo-Pacific. Beijing’s actions, so far, have been steady but incremental such as its continuous encroachment against Taiwan and in the Indo-Pacific. There is good reason for such incrementalism, or as it is often called, salami-slicing tactics. It leaves adversaries with difficult choices and allows the perpetrator to make steady advances, reducing the risk of pushback. It also puts the perpetrator in a better situation if circumstances eventually result in a full-blown war. China still retains these advantages, and changing tactics now might not be wise.

Of course, as a counterpoint, expecting wisdom from state decision-makers may also not be prudent, and Beijing under President Xi Jinping has been particularly strategically inept. Equally, China may just be lucky that the international circumstances turned propitious just as it was about to embark on a major venture. Going back to the 1962 India-China war, it is unlikely that Beijing planned the timing to coincide with the Cuban missile crisis — they could not have known it would erupt. It was a happy coincidence for China and a particularly untimely misfortune for India. Simply put, this suggests that whatever the constraints operating on Beijing, it would not be strategically smart to assume they would stay China’s hand.

Also read: Is the US fanning an ‘Arab Spring’ flame in poll-bound Bangladesh?

Plenty of blame to go around

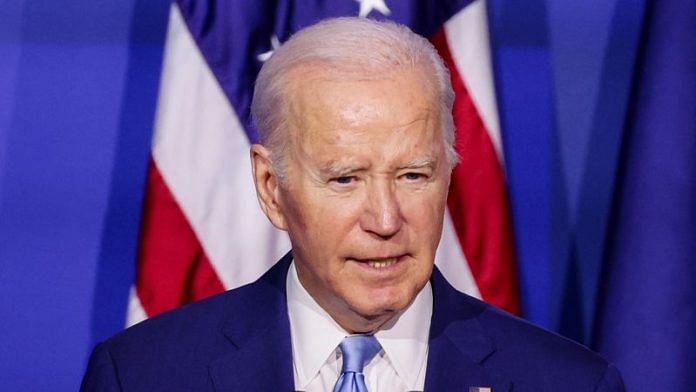

Washington may need to share part of the blame for its current predicament. In Ukraine, President Joe Biden’s administration has been so focused on preventing escalation that it delayed the transfer of significant capabilities that might have made a difference on the battlefield, leading to ‘escalation paralysis’. Beginning with artillery systems, and going on to ballistic missiles, tanks, and combat jets, the incremental supply of different capabilities meant that Ukraine was quite possibly denied an opportunity for outright victory. The supply of tanks without supporting combat fighters or helicopters, for example, meant that the Ukrainian summer offensive had no chance to become the vaunted, true combined arms offensive. And the delay in supplying even these meant that the Russians had sufficient time to prepare well-fortified defences, which ultimately broke the Ukrainian offensive. Part of the fault is in Ukrainian and allied training, but there is plenty of blame to go around.

This is not to suggest that Washington’s concerns about escalation were entirely without merit. But early US and Western supplies did not elicit Russian escalation, which should have compelled the White House to recalibrate its strategy. Instead, caution continued to prevail, which has now ensured a much longer war and possibly even prevented a clear Ukrainian victory — neither of which is particularly helpful to the US or its partners.

As long as Ukraine is unable to win and end the war, the US will be forced to stay committed to Kyiv. And the longer this drags on, the greater the possibility that other crises will arise in other parts of the world that further strain American capacities. Leaving Ukraine to its fate is an even worse option because that would potentially lead to a more unstable Europe and a greater diversion of American attention from the Indo-Pacific.

Also read: Biden’s focus was on Xi’s car, character. It shows the limits of success in…

Another thing that matters

Of course, capability is not all that matters. Willingness does too. That’s another area of concern regarding the US. There is little doubt that America is growing weary of its global commitments, and it’s a sentiment that is prevalent on both the Left and Right side of the US political spectrum, even if they are justified differently. The Biden administration has done a remarkably good job of holding the line on this issue but has not had the willingness to promote further liberal trade agreements, for example, a clear recognition of what has become permissible and what no longer is within the US political realities.

If former President Donald Trump should be re-elected next year—opinion polls appear to give him a slight edge—the situation could become a lot worse. Trump’s key advisors in his last administration were generally part of the mainstream of US politics, even if they were conservatives. This time, it may very well not be, which could mean that the US willingness to defend the existing order in the Indo-Pacific will very likely be open to question and could lead China to test American commitments.

Ultimately, there is not a whole lot that the Indo-Pacific powers can do. Unlike Europe, many powers in this region are already ramping up their military capabilities, and there is a limit to how far they can go. It won’t compensate for American power. In addition, their willingness to cooperate within the region will likely be a function of Washington’s readiness to be an anchor for any regional security order. If this is called into question, either because of American lack of capability or enthusiasm, the future of the region will be much more unstable and dire than most analysts and governments assume.

The author is a professor of International Politics at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), New Delhi. He tweets @RRajagopalanJNU. Views are personal.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)