This ‘Writings on the Wall’ article by Shekhar Gupta was first published ahead of the 2012 Gujarat assembly elections.

In Gujarat, his consumer, the voter, needs pride, self-esteem. He is delivering it through his product: economic success. The Congress has no real counter offer.

Why we call this occasional series from diverse zones of India, often during the elections, ‘Writings on the Wall’, needs repetition, particularly in times when even soundbites have been reduced to no more than 140 characters. So many years of training as a reporter have taught me that one of the more interesting ways of checking out what is going on in our country, what is changing, for better or for worse, or not changing at all, is written, literally, on our walls. So if you go to the most prosperous zones, take Punjab for example, you will find Mercs, credit cards, housing loans and easy visas and immigration to the US, Canada and now New Zealand. You go to a flourishing green revolution zone like Andhra Pradesh and the walls will be selling you tractors, fertilisers, gold loans. In Nitish’s Bihar, even the boom in branded underwear, sold mostly on the walls, tells a story of small new household income surpluses and, of course, aspiration. Go anywhere in India, including the unfortunate villages in the Kosi devastation zone of Bihar, and you will see saria (iron rods) and cement selling on the walls, underlining the construction boom, and the fact that the days of “kuchcha” housing are rapidly ending. We have noted through our travels in recent years that the one big change sweeping the country, and written on the walls, is the desperate clamour for modern, English-medium education.

Truth to tell, at first glance you might think this theory no longer works in Gujarat, as many other postulates of Indian politics, including anti-incumbency, don’t. Having built this idea over so many years, it is a bit startling to search the walls for that one message that tells you a story of change, aspiration, something, and yet find nothing. And then the penny drops. The story of Gujarat is indeed written on its walls. Or rather, these blank walls tell you the story.

You drive hundreds of kilometres on Gujarat’s brilliant highways, as we, the usual motley group, the self-styled Limousine Liberals, did last week, and look left and right. There are, what else, but walls on either side. These are shiny, new and modern factories, wall-to-wall, as you’d find in no other part of India. And these are not even Reliance, Essar, Adani, Cipla, Cadila, the usual suspects. There are hundreds of others, with names you have never heard, nor seen on the business channel stock market tickers. And these are not the factories and smoke-stacks you see in old movies. These are buildings with neat, spotless white, beige or dull pastel walls with nothing written on them. No slogans, no graffiti, no advertising. Another thing you will not find is a ubiquitous factory fixture in most parts of the country: the trade union’s red flag. Dahej, Ankleshwar, Hazira, Jamnagar, Mundra, Halol, Dholera and Pipavav, and now the new auto hub of Sanand, are global-size industrial zones. Obviously, there has also been a small and medium — but modern — industry boom in the state. A vast majority of these are manufacturing industries. Are they here because the moneybags love Narendra Modi? They are here because Gujarat provides them ample power, industrial peace, rail and road infrastructure, law and order and a non-rent-seeking bureaucracy and political class. They have reason to be grateful to Modi. And so do millions of Gujarati beneficiaries of this boom. That’s why they keep re-electing Modi. Not because a thousand Muslims were killed under his watch in 2002. That, though, is a factor as well, but we will return to that later, in fact, in the second part of these writings, tomorrow.

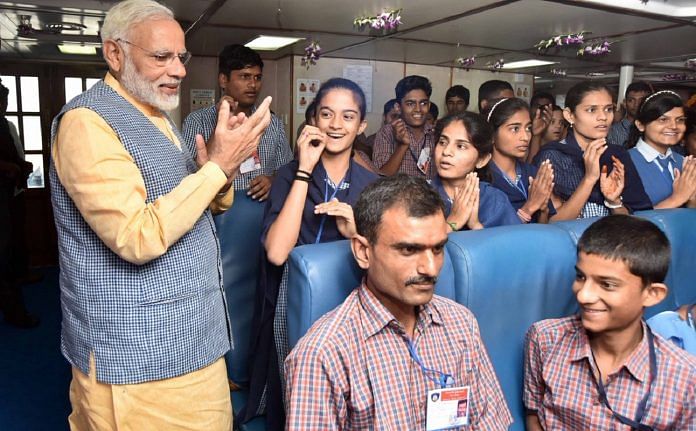

Rahul Gandhi spoke the truth last week when he said Modi is good at marketing himself. Modi is, in fact, brilliant at it. But you must admit that he also has a good product to sell. We find him at Dabhoi, just 40 minutes from Vadodara. This is a Congress stronghold and he is trying to wrest it from Siddharth Patel, son of another Gujarati legend, in fact, its last Congress chief minister, Chimanbhai Patel. Modi, 2012 is a far cry from Modi, 2007 or Modi, 2002. He still does not reach out to his minorities. But now he calls “all six crore Gujaratis” a family, his family. That, for Modi, is inclusive. He talks about peace, the absence of curfews for a decade and so on. But the real message is about his economic success.

“In so many states,” he says, “people leave their homes to search for a living elsewhere. How many Gujaratis have to do this? You might go for enterprise, or to make more money, but for a living?” “None,” the crowd says. And do you know how many lakhs of money orders are sent home by people from other states whom you have provided work in Gujarat? You know he is now a regional leader more than a mere BJP chief minister. His consumer, the Gujarati voter, needs pride and self-esteem. He is delivering it through his product, his economic success. His appeal is to ethnic pride, but his message the exact opposite of, say, the Shiv Sena in neighbouring Maharashtra.

Some of his sharper edges may have smoothened out, but the undertone is pure Modi. “Your money is safe with me,” he says, because “I have no sons or daughters or ‘jamai’ (son-in-law)”. And before you start drawing lazy conclusions, he is not talking about Sonia Gandhi’s jamai but Keshubhai Patel’s. How did we decode this? His crowds told us. His persistent reference to “Sonia Madam” and “Rahul Baba” underlines his idea of them as laughable aliens. He does not attack anybody else in the Congress. The prime minister is dismissed as “Maun”Mohan Singh. No other Congress leader, local or national, is ever even mentioned. Frankly, nor is anybody from the BJP. No Vajpayee, no Advani, no Shyama Prasad Mukherjee, Deendayal Upadhyaya. He is fighting in a bigger league of his own, for a bigger prize. That is why the only rivals he targets are Rahul and Sonia, in that order. And he is his own inspiration. Important thing is, his voters are buying his message.

He promises zero freebies or goodies. The best thing on offer from him is another five years of Modi. He discounts, for now, the talk of his inevitable move to Delhi. But everybody knows what this is about. This is an election to empower Modi to sideline the national leadership of his party, half of which already depends on him for one thing or the other. Take note, for example, of the fact that L.K. Advani and Arun Jaitley were both in Gujarat on Monday to cast their votes. They are not from Gujarat, but have their Parliament seats from here, courtesy Modi.

The Congress has learnt one lesson well from its past defeats in Gujarat. It is not seeking another verdict on the riots of 2002. That plays straight into Modi’s hands. It has a very slick and clever advertising campaign using unknown brand ambassadors and models and promising an entire range of populist freebies. One of these, free houses for the urban poor, has attracted some interest. But it does not have a larger story to counter Modi’s. Its campaign looks richer than Modi’s, but is caught within its local, organisational inadequacies and ideological confusion. The Congress wants to say that the industrialisation of Gujarat did not start with Modi. And that is a fact. It was a heavily industrialised state much before he arrived. But how does it say this?

We heard Sonia Gandhi at Kalol, not far from Gandhinagar, make this point. And which were the three companies she said her party had brought to Gujarat? IFFCO, KRIBHCO and ONGC. All public sector companies. Congress people are too ideologically shy to claim credit for bringing private sector investment. And this is not a PSU-type state. The only Congressperson to break ranks is Urmilaben. She breaks her long silence in her modest Dabhoi home to say that her late husband, Chimanbhai, brought Reliance, Essar and Cadila to Gujarat. Talk of PSU investments does not strike a chord in a state that is home to Ambani, Ruia, several multinationals and now Tata, which has produced its own entrepreneurial successes in the Mehtas of Torrent, Adani and even Karsanbhai Patel of Nirma, and where so many of the farmers also have demat accounts.

Shyness to engage with corporate India apart, to say that the Congress party’s approach is outdated will not be entirely fair. Nor will it tell the full story. The party has simply not found an answer to Modi, the leader, or the performer, or the tactician. The party counted on Keshubhai Patel causing a vote split. But Modi is not complacent.

Ahmed Patel is the Congress party’s most important general secretary, arguably the third most powerful leader in the party, and a wonderful host. He was chatting with us over a sumptuous high tea at his ancestral farmhouse, ringed by kesar mango orchards in his village of Piraman, near Ankleshwar. Suddenly, he was interrupted, sort of rudely, by a phone call, and walked back indoors. You know it has to be something really pressing for Ahmed Patel to leave his guests by themselves even for a few minutes. This was when he had heard from the prime minister’s office that Modi had released a letter he had written to the PM protesting against any deal on Sir Creek with Pakistan. Now, Sir Creek is in Kutch. Modi had just made a move to counter the appeal of caste with anti-Pakistani nationalism. The look on Ahmed Patel’s face was part bemused, part disgust and part how-do-you-deal-with-this-man.

The Congress party sees the pitfalls in harking back to 2002. Yet, ideologically, that emotion is too strong to discard and move on. That’s why it has outsourced Shweta Bhatt’s campaign against Modi to leftist NGO activists. That’s why Rahul Gandhi’s repeated story on Gandhian sacrifice and forgiveness, reminding people that the Mahatma came from their state and that he was their moral compass, not Modi. But it isn’t working.

We caught up with Rahul in Limdi in Dahod district, in the heart of one of Gujarat’s tribal zones, on the border with Madhya Pradesh. He sounds sincere, and his waist-coat with Warli wall painting (unique to the tribes here) motifs, draws immediate attention. But much of his spirited, spirit-of-Gandhi speech did leave a lot of his audience, though mostly Congress loyalists, confused. Most of them were born after Indira Gandhi was assassinated. It is tough for them to connect with Motilal Nehru, even Jawaharlal, and draw the link with Mahatma Gandhi. Besides, Gandhi was never quite the role model in Gujarat, which only pays token respect to him by maintaining prohibition and thereby allowing a flourishing bootlegging business. This is testosterone-laden Gujarat of 2012. Modi, in so many ways, is seen as its first real leader. And the founders of Reliance, Torrent, Adani and Cipla are its role models.

Driving to Limdi from Godhra, we make a short stopover at a lone house on the road in village Ghoomni, near Neemkheda. Kamlaben Mawi, maybe in her late forties, lost her husband, Kanubhai, to a heart attack last year. She now takes care of her 70-acre family farm. In her home, the TV is on, showing Rahul Gandhi speaking, live, at a rally. I ask her if I can flick channels to check how India are doing at Nagpur and she says, forget it, they are hopeless, we need a new team. Do you get power, I ask. And the answer is, of course, 24 hours. For her agricultural connection, she says, power comes on alternate weeks, during the day or night. There is no power problem. And water? It used to be, but now she has installed “teepak padhhati” (drip irrigation system) and there is water in the check-dam close by. Then I ask her, shamelessly, her caste and her daughter-in-law says they are “Hindu Bhil”. So here is Kamlaben Mawi, a Bhil tribal with zero education. But she can take three crops from a 70-acre farm using drip irrigation. She can also lecture you on what is wrong with Indian cricket. It tells you several things. First, that one unique Gujarati trait is entrepreneurship, and this cuts across caste, ethnicity and religion. Second, that power, or electricity, is the great new equaliser and force-multiplier even in the most distant rural, tribal India. Combined with 24-hour TV, it can even fill the knowledge and literacy gap. And third, that by continuing to harp on Modi’s “false” claims of 24-hour power and rural anger, the Congress has got its basic politics all messed up.

I do pick up the remote and switch to Star Cricket briefly. Both of us look at the scoreboard and wince. And I ask her the question that journalists always ask, but which is rarely answered by an Indian voter. Who will you vote for? Ours has always been a Congress parivar, she says. We will never vote for any other party. But Narendra Modi is a great man, a leader, not a party, not BJP. So this time, for her, it might be different.

India awaits a similar Report Card in 2019.