The Gujarat govt hasn’t done anything for a decade and a half, but keeps on blaming others. Also, it keeps diverting from agricultural and drinking water.

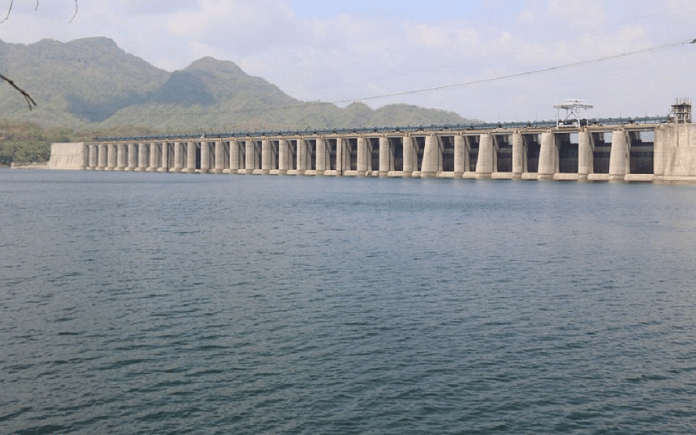

There is a severe water shortage in the Narmada dam and the Gujarat government has said that it will not supply water for irrigation. Many are shocked that this is occurring in spite of bountiful rainfall last year.

There are two factors at play here: the immediate, and the long-term and structural.

Water shortage in Gujarat this year is as much on account of the Narmada’s hydrology as the technology of the Sardar Sarovar Project canals.

Before the election, Vijay Rupani, the chief minister of Gujarat, had patiently explained in a public meeting that 62 per cent of the distributaries are complete up to the village level. So, since 2002, when water was diverted into the canals from the dam, a lot of the work is yet to be done.

Narendra Modi as chief minister had inherited a dam completed by the Congress governments, who he berates constantly. But he should have completed the work in five years (the original SCADA tender is still half done).

The NITI Aayog’s vision document sets the target for 2019, but the chief minister says that land acquisition efforts would be difficult.

So this year, half or more of the canal water will not reach the village. Also, a lot of SSP water is used in the Sabarmati Riverfront project.

As originally planned in the ‘Planning for Prosperity’ vision, the priority has to be given first to drinking water, and then agriculture. Not the riverfront. The farmer would have got more water, which at present goes waste because the canal work is incomplete. In fact, the possibilities are even greater.

The SSP plan was built on the basis of a computerised canal operation system. But the government keeps on tendering it every few years and the contract is not offered. The possibilities are endless, but let’s start at the beginning. The more lower-level canals we build, the better will be our Rabi and summer, and the less our thirst. The time is now.

The government has not done anything for a decade and a half to cut losses but keeps on blaming others. Also, it keeps diverting from agricultural and drinking water.

There are, however, larger design issues involved too.

The earlier hydrological and ground water models need to be reworked. The socio-economic benchmark studies done for each taluka need to be redone and benefits of the project tracked in a more systematic way. All this will not cost much as the technology has improved a lot with Google Earth and other tools. This will help us in better implementation of the project.

The computerisation of the operation of the main canal and the branches and distributaries is of the highest importance because water becomes more scarce as the upstream states begin to use their shares. This will improve the delivery efficiency of the system. Conventional water delivery systems have a delivery efficiency of about 40 per cent.

The SSP plan is not cast in stone. Over decades, an economy develops and changes. Technology gives many new possibilities. Planning is meant to be a flexible business in its best variants.

The plan had anticipated all this. There is some urgency to getting back to the original design configuration of the SSP plan. As long as upstream use of Narmada waters was not according to Madhya Pradesh’s full entitlement, we as the lower riverine state of Gujarat were entitled to all the water flowing down from the Sardar Sarovar Dam. Upstream water use was little, in Stage I. But with further development upstream now, we would only get what is our entitlement.

As the flows dwindle after MP began to use more and more of its share, the computer controlled systems, planned for SSP way back in 1985, are needed to maximise timely deliveries with scarce water.

Yoginder Alagh is the chancellor of the Central University of Gujarat. He is a former Union minister and an economist.