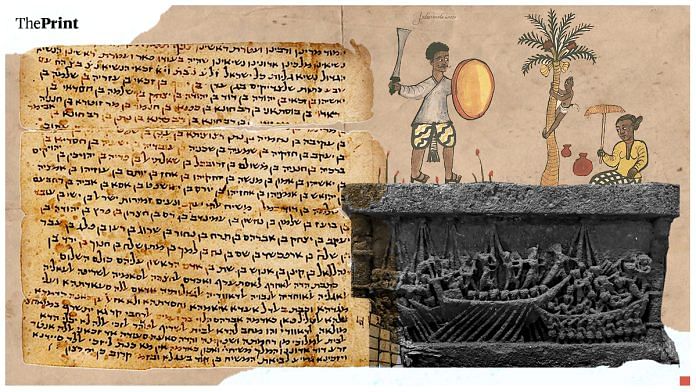

When we think of “Abrahamic” religions in 11th and 12th century South Asia, the political narrative is most often of the expansion of Islam. However, this was also a crucial period for Judaism. Driven by complex incentives, large numbers of Jewish and Muslim merchants immigrated, traded, and raised families on Indian shores. Many Jewish merchants stored their correspondence in a synagogue near Cairo, which has miraculously survived nearly a thousand years in the desert weather. Today, this archive—called the Cairo Geniza—offers us a priceless insight not only into medieval Jewish Indians, but also into the dynamics of medieval Indian trade.

Rise of the Konkan coast

The late 10th century was momentous in Indian Ocean history. In 972 CE, Manyakheta, the great capital city of the Deccan Rashrakuta empire, was sacked. In 973, Al-Qahira (Cairo) was established as the capital of the Fatimid Caliphate in Egypt. And in 987, the Song dynasty of China sent embassies to the Indian Ocean, promising facilities and licences to international merchants. Around the same time, the Chola king Rajaraja I (r. 985–1014) embarked on campaigns to dominate trade routes in Southern India.

In the Konkan region of India’s west coast, the Shilahara dynasty also set out to capture trade routes. In Coastal Trade and Voyages in the Konkan: The Early Medieval Scenario, historian Ranabir Chakravarti used the dynasty’s inscriptions to argue that they set out to create a unified trading region, with major emporia at Chandrapura (near present-day Old Goa) and Balipattana (present-day Kharepatan). Shilahara kings fought a number of naval campaigns against the Kadambas of Goa, commemorated in impressive hero-stones depicting ship-to-ship engagements.

As in medieval Gujarat, merchants played major roles in these polities. In the Panjim copper plate inscription of the Kadamba king Jayakeshi II, published by George Moraes in The Kadamba Kula, an Arab (or Persian) Muslim by the name of Sadhana is named as the governor of various Konkan ports. The Shilaharas, meanwhile, relied on a dynasty of merchant fleet owners led by one Durga Sresthi, as studied by Chakravarti.

Quite rapidly, Chandrapura became one of the most important ports on India’s west coast, acting as an entrepôt for trade into the Malabar region. Known in West Asian sources as Sindabur, in 1116 it attracted the curiosity of a Jewish merchant of Tunisian descent, Allan bin Hassun. Allan’s career was studied by Shelomo Dov Goitein, a renowned expert on the Cairo Geniza documents, in Portrait of a Medieval India Trader: Three Letters from the Cairo Geniza. Allan was the nephew, son-in-law, and foster son of the respected merchant Arus bin Joseph, who had settled in Egypt and ran a textile business with his lifelong business partner, a Syro-Palestinian Muslim by the name of Siba. Arus, writes Goitein, was “renowned for his generosity and helpfulness”, and many letters of medieval Jewish merchants refer to him and his Syro-Palestinian partner with great affection.

In 1116, Allan set out on an adventure. Though Arus and Siba were hesitant, Allan—after a sales trip around Yemen, selling to Arus’ long-standing Arab partners—decided to sail to Chandapura. (Before doing so he sent a letter to Arus complaining about his cousin Joseph, who apparently had taken to staying in a brothel and to heavy drinking). Allan had a flourishing career in India, where he expanded the family business into iron and pepper export. These were also the mainstay of another Tunisian Jewish merchant settled south of Chandapura: Abraham bin Yiju. Abraham offers us an extraordinary glimpse into the medieval metals trade.

Also Read: How India’s coastal Muslims helped it become wealthy, successful economy in medieval era

The life of a Jewish Indian

Abraham was a contemporary of many important South Indian kings, including Vikrama Chola (r. 1118–1135) and Hoysala Vishnuvardhana (r. 1108–1152). In her pathbreaking multidisciplinary study of his life, Abraham’s Luggage, historian Elizabeth Lambourn points out that he was a bit of an adventurer. He had to flee Aden, where many Jewish merchants lived, owing to a falling out with the Sultan. He arrived on the shores of what he called Malabariyat or “the Malabars”, owing to the Malabar coastal region’s political instability, around 1132. Though there were some older Jewish communities there, it was relatively new ground for Tunisian families like that of Abraham. And despite its political instability, local rulers remained friendly and welcoming to traders.

There, Geniza documents reveal that Abraham purchased—and manumitted—a slave woman by the name of Ashu, who he calls a “Tuluva”. (This, incidentally, is one of the earliest non-India mentions of “Tuluva” as an ethnicity.) By 1135, writes Lambourn, Ashu and Abraham had a son, Surur. It is possible that Ashu converted to Judaism. Intriguingly, in one of Abraham’s letters, (published by Goitein in India Traders of the Middle Ages: Documents from the Cairo Geniza) he mentions that his brother-in-law was a Nair—later one of Kerala’s dominant castes. It’s not clear what this Nair’s relationship to Ashu was. Abraham went on to have three children, two of whom survived till 1149, when he finally returned to Egypt. His brothers, meanwhile, were in Sicily and remained in touch with him.

Settling in the vicinity of Mangalore, for 17 years Abraham ran a flourishing import/export business. He imported copper and tin, manufactured them into new objects using local talent, and sent them back to Aden. (At least some of the imported copper and tin came from as far afield as Spain, and it’s possible that they found their way into medieval Indian bronze idols). Medieval Jewish networks, then, extended from the Mediterranean Sea to the Indian Ocean and were crucial to connectivity. Many of them spoke and wrote Arabic, and we can guess, given Abraham’s business ventures, that they were conversant with Indian languages as well.

Abraham exported to West Asia massive quantities of iron and steel ingots, especially high-carbon steel, which medieval South India was particularly known for. He also dealt in betel nut and pepper, and served as a reliable partner for other merchants based in Aden. In subsequent centuries, Mangalore, his base, would also become known for rice export to Africa and Arabia; Abraham seems to have entered this market in a crucial phase of the Tulu coast’s transition to agrarian exports. Through his correspondence, we also learn that he had many Indian business partners, including a certain Sesha Setti, and that one of his slaves, Bomma—a Tulu—was frequently in and out of Egypt. Bomma was very well regarded by Abraham’s partners, except on one unfortunate occasion, reported by Ranabir Chakravarti in Indian trade through Jewish geniza letters (1000–1300), when he showed up drunk to a business meeting.

This high regard for Indians was no exception. Through the Geniza letters, we find mentions of many Indians, including a certain Pattana-Swami, the merchant prince of an unspecified port, and Timbu, a beloved friend of Judah ha-Kohen, a merchant active in 1145. We find Jewish merchants trading in camphor, which was directly being sourced by Tamil merchants in Sumatra, in the aftermath of the Chola raids on Southeast Asia. We also find close ties with Yemeni, Syrian, Iraqi, Palestinian and Arab merchants. One of them, Ali bin Mansur al-Fawfali, had a surname derived from the Sanskrit pugaphala, betel nut, and traded in betel before purchasing a ship and partnering with Jewish traders.

To all of these people, Indian ports offered fair, honest treatment and opportunities for friendship and profit. All of this seems almost unimaginably distant in 2023, with bloody boundaries drawn between religions and ethnicities that once thrived in a borderless world.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of Lords of the Deccan, a new history of medieval South India, and hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti. Views are personal.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval‘ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)