Jaiswal, Oswal, Jain, Shah, Khandelwal, Agrawal. These names appear across the length and breadth of India today — in commerce and manufacturing, markets and politics. They are probably borne by some of Thinking Medieval’s readers. Yet, few are aware of the fascinating history behind these names—a tale of social mobility, high-stakes politics, and the evolution of medieval India’s best-attested commercial institutions.

Communities and corporations

In December 2022, the National Museum in Delhi organised an exhibition of Jain manuscripts dating to between 1000–1500 CE or so. Produced with magnificent calligraphy of gold leaf, richly coloured with red and blue pigment, these manuscripts were obviously commissioned by fabulously wealthy individuals. Many of them were, of course, medieval Gujarati merchants. In their own time, they were power brokers whom every great figure—whether king or religious teacher—had to deal with; yet they are strangely invisible to us today.

When we think of India’s past wealth and glamour, it is most often a royal court that pops into our minds. But, arguably, far more fiscal muscle was controlled by merchants. The “invisibility” of the medieval West Coast merchant is also tied to the fact that elements of South Asian culture are not as visible in the Western Indian Ocean (WIO) world, compared to the Eastern Indian Ocean (EIO) world. Certainly, in the East African coastline and Arabian Peninsula, one does not see the spectacular Hindu-Buddhist temples that one does in Southeast Asia. But this by no means suggests that Indians were any less present in the WIO world. When interacting with the region’s equally ancient urban and commercial networks, Indian presence took different forms. Dozens of Indian merchant traders are named in medieval Egyptian Jewish texts dating to around 1200 CE — as shipwrights, captains, and bankers.

The appearance of these Gujarati merchants on the historical scene is a sign of the increasing density of exchanges in the WIO. In Trade and Traders in Western India AD 1000–1300 (1990), historian VK Jain provides the most comprehensive overview of these individuals. Iran, Mesopotamia, and Gujarat, which have had flourishing trade ties since at least the Harappan period over 4,000 years ago, have frequently exchanged financial, agrarian, religious, and commercial ideas. By around 1000 CE, developments in irrigation technology in these regions—using clockwork and ox-powered mechanisms—led to rising agricultural yields. In Gujarat, this prompted local landowners to take to trade (Jain 1990, page 213). Many of these landowners actually came from nascent Rajput castes. According to Jain, some Oswal, Jaiswal, and Agrawal merchants still claim Kshatriya origin as a result. He cites a 13th-century inscription to make this explicit: In Epigraphia Indica XI, page 61, a man bearing the surname Soni (now associated with Baniyas) refers to his grandfather and great-grandfather as Thakurs. Other castes with social and financial capital also took to trade with gusto; various medieval texts and grants mention Brahmins selling betel, horses, textiles, wine, ghee, and more (Jain 1990, page 212).

These merchants organised themselves into collective assemblies with their own laws and regulations. According to the medieval legal commentator Medatithi, “Certain principal tradesmen… used to approach the king, and offer to pay him the royal tax fixed upon verbally. After the king agreed to it, they joined together and laid down among themselves certain rules… If anyone transgressed these rules, he was punished for acting against the guild laws.” (Jain 1990, 230). The king could not intervene in these laws except in the most extreme situations. We have examples of similar collective mercantile action in South India as well. However, South Indian traders of different occupations banded together into enormous transregional merchant corporations such as the Ainnuruvar or Five Hundred, studied by historian Meera Abraham in Two Medieval Merchant Guilds of South India (1988). The Ainnuruvar is attested from Telangana to Sri Lanka to China. But merchant corporations in Gujarat were much more locally-constrained and focused on specific occupations or merchant lineages. While South India’s merchant families did not survive the demise of corporate assemblies in the 15th century—a topic we won’t touch upon here—Gujarati lineages did, accounting for the long continuity of these identities.

Also read: How an Odia queen became medieval Sri Lanka’s greatest politician

Merchants and generals

Some merchants made sure that royals could not interfere in their affairs. Then there were others who became integral to the activities of royals. Medieval Gujarati inscriptions and stories are full of tales of merchants who worked as royal ministers and even generals, gradually becoming courtly aristocrats in their own right. Many of these merchants were also Jain, and are known to have commissioned large libraries of manuscripts, some samples of which were present in the National Museum’s aforementioned exhibition.

Merchant-generals had extremely dramatic careers, but, as these opulent items reveal, the rewards were worth it. For instance, a ghee merchant called Udayana, originally from Jalor in present-day Rajasthan, made a fortune for himself in Karnavati (present-day Ahmedabad), where he managed to impress King Kumarapala (1143–72 CE) of the Chaulukya dynasty. Appointed as the governor of southern Gujarat, Udayana was killed while fighting a local chief in Saurashtra (Jain 1990, page 237). One of his sons was also a minister of Kumarapala, in which capacity he fought off invasions from the Silahara dynasty of the Konkan—who, as it happens, were bankrolled by local Muslim merchants. We will explore that more in a later column.

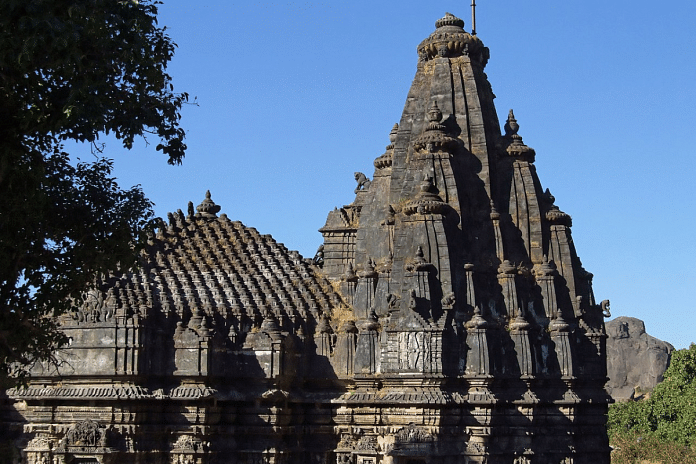

A slightly later Chaulukya king, Siddharaja (1093–1143 CE) was even more dependent on merchants, possibly, according to Professor Jain (1990, page 241), to pay for the military campaigns that were needed to keep trade and tribute flowing. Two of them ruled as regents during the king’s minority, and one of them, Santu, trained him in the arts of rulership. While returning from a raid to Madhya Pradesh, Siddharaja’s army was waylaid by a large force of Adivasis—Bhils—and he only managed to escape after Santu sent him reinforcements. Another merchant-general by the name of Sajjana, who built the famous temple of the Jain Tirthankara Neminatha at Girnar, was defeated and raided by Chahamana Vigraharaja IV—the uncle of the much more famous Chahamana Prithiviraja II (Prithviraj Chauhan). Building a temple was a sign of tremendous wealth and prosperity; for a merchant to do so indicates a career of high risks, rewards, and defeats.

But in many ways, all these were just the prelude to some of the grandest structures ever built by medieval Indian merchants—the marble temples of Mount Abu, which we’ll visit in next week’s column.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of Lords of the Deccan, a new history of medieval South India, and hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval’ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)