From where we sit in the 21st century, we are all too used to India being an “exotic” country: the land of spices and colours, drugs and sounds, strange to the Western imagination, which dominates the global cultural landscape. As silly as these exoticisms are, I was surprised and delighted to hear that medieval India had its own idea of “exotic” foreign lands from where strange peoples brought rare and luxurious items for consumption.

To explore them, we’ll journey through one of the most fascinating strands of Sanskrit literature: Kamashastra, literature pertaining to the refinement and cultivation of pleasure.

Kamasutra more than what you think

When texts like the Kamasutra were discovered by colonial officials in the 19th century, they responded—almost universally—with Protestant revulsion. The image of medieval Indians as hedonistic, “degenerate” pleasure seekers took deep root throughout the 20th century—to the point where much of medieval courtly literature is yet to be studied and translated.

Our conception of “Indian civilisation” today is dominated by the handful of ancient texts, which appealed most to colonial writers and early nationalists. Meanwhile, texts like the Kamasutra have been reinvented to support modern conceptions of sexual liberation. However, both these reinventions actually miss a crucial strand of medieval history: the nagaraka. The refined and cosmopolitan man-about-town pursued—unashamed by later Victorian-esque morals—a refined enjoyment of all the world’s pleasures.

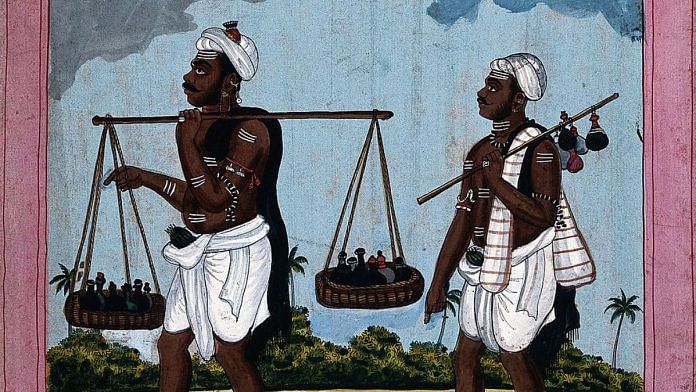

Such connoisseurs wrote a number of texts throughout the early medieval period, roughly 600–1100 CE, exhibiting their knowledge of arts such as perfumery, gemology, painting, erotic love, dance, and music. All these arts were believed to delight the senses: an idea that some earlier South Asian thinkers would have found troublesome indeed. Though the Kamasutra is the most famous of these texts today, in the medieval period it was rivalled by others such as the Gandhayukti of Lokeshvara and the Nagarasarvasva of Padmasri.

In The Incense Trees of the Land of Emeralds: The Exotic Material Culture of “Kāmaśāstra, Professor James McHugh, an expert on the material culture of South Asian religions, studied how these texts discuss the ingredients of perfumes, such as sandalwood, aloeswood, musk, saffron, camphor, nutmeg, cloves, cubebs, and various resins. As McHugh shows, we can get a dazzling sense of the Sanskritic imagination through poetic manuals compiled by experts such as Rajasekhara, a court poet from west-central India in the 9th-10th centuries CE.

Rajasekhara’s world was divided into four quarters corresponding to the cardinal directions. He describes each quarter in relation to his geographic imaginary, which seems to have extended from present-day Pehowa in Haryana to Varanasi in Uttar Pradesh, from Mahishmati in Madhya Pradesh to a certain “Devasabha” in the west, whose location is unknown. Each region, to Rajasekhara, contained several countries, a great mountain, and produced exotic goods. Interestingly, to him, South India was a place where cobras hung from sandalwood trees, and spices grew abundantly. Danger and luxury went hand-in-hand, it seems. Medieval Europeans also believed that South Indian pepper trees were guarded by snakes.

That’s not all, of course. Rajasekhara describes a number of “foreign” countries to the east, including the kingdom of Pragjyotisha (Kamarupa in present-day Assam), which produced aloeswood and musk; to his north were Turushka (Turks), Shaka (Scythians), Bahlika (Bactria) and Huna (Huns), which provided horses, pine, deodar, and saffron. The Scythians and Huns were extinct at the time but still seemed to feature in the poetic imagination. Rajasekhara also mentions a certain country called “Yavana” to his west, alongside other countries such as Saurashtra and Bharuch. Yavana was the source of dates and camels, and possibly refers to Arabia.

It is rather interesting, considering that most regions of South Asia at the time had Sanskritised, temple-building kingdoms, that Rajasekhara still regarded them as exotic and “foreign” regions—as foreign as the Arab and Turk worlds. His imagination of the world was not guided primarily by religious practices, but rather by material culture. To his mind as well as to that of his Kamashastra-writing contemporaries, the rest of the world produced refined goods to be collected and utilised by the cosmopolitan connoisseur, including, for example, automata. Medieval perfumery even borrowed ideas from political treatises, an indication of the interdisciplinary mastery of these connoisseurs. Perfume ingredients are given a complex hierarchy of relationships, such as “ally”, “neutral”, and “enemy”.

It is therefore not surprising that the most refined of medieval connoisseurs were the most politically powerful. The kings-of-kings, who conquered and received tributes from all four quarters, thus quite literally enjoyed the earth. In royal courtly texts such as the Manasollasa, composed by the Deccan emperor Someshvara III in the 12th century, goods from everywhere appear, testifying to a rich, sprawling engagement with the world—Persian horses, Arabian incense, Kashmiri saffron.

Also read: Jaiswals, Oswals, Shahs—Gujarat’s trading families once wielded more power than medieval courts

Conquest and goods

In the early modern period, starting from about 1500 or so, market demand for “exotic” goods funded European colonialism and conquest. This brings up the question: If medieval India was so curious about the world’s goods, then did it go out conquering to obtain them? Yes. Exotic produce is frequently mentioned as tribute in early medieval inscriptions and texts within the subcontinent, but that’s not all. Possibly, a major motivation for Rajendra Chola I’s famous raid on the Srivijaya polity of Sumatra (modern-day Indonesia) was Tamil merchant guilds’ demand for goods such as sandalwood and camphor. While I will make this argument in detail elsewhere, here is some evidence to support this idea.

In his book chapter The Tamil Diaspora in Pre-Modern Southeast Asia: A Longue-Durée Narrative, part of the edited volume Sojourners to Settlers, historian Sureshkumar Muthukumaran mentions that medieval Tamil commentators were aware of over a dozen varieties of camphor—many of which grew on Sumatra. And archaeologist E. Edwards McKinnon, in Mediaeval Tamil Involvement in Northern Sumatra, C11–C14 (The Gold and Resin Trade), writes of two armed Tamil merchant settlements in Sumatra—Kota Cina and Barus. Inscriptional, ethnographic and archaeological evidence suggests that merchants confronted and cajoled inland peoples such as the Karo to provide them with aromatic resins, demanded both by courtly elites and the increasingly complex rituals of temple-based Shaivism.

Interestingly, medieval perfume culture did not remain static, nor did it go extinct. In the late 13th–early 14th centuries, a Svetambara Jain named Thakkura Pheru, who worked as a mint officer for the Khalji and Tughlaq Sultans, wrote a text called the Dhatutpatti. It reiterated many Sanskritic ideas of the origins of perfume ingredients.

Indeed, as McHugh writes in another paper, The Disputed Civets and the Complexion of the God: Secretions and History in India, contact with the Turko-Persian world popularised new ideas in the Sanskritic aromatic imagination as early as the 11th century—even before the establishment of the Delhi Sultanate. Among these were the use of civet and ambergris, as well as related technical vocabulary. Indeed, civet secretions continue to be used in the great temple complex of Tirupati, Andhra Pradesh; they were once worn by Indian elites from the 12th century Someshvara III to the Malwa Sultan, Ghiyath Shah, in the 15th century.

All of this flies in the face of all ideas that medieval South Asians were somehow insular or uninterested in the rest of the globe. The exotic material culture of Kamashastra, and its early modern heirs, demanded an active and constant engagement with the world.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of Lords of the Deccan, a new history of medieval South India, and hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval’ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)