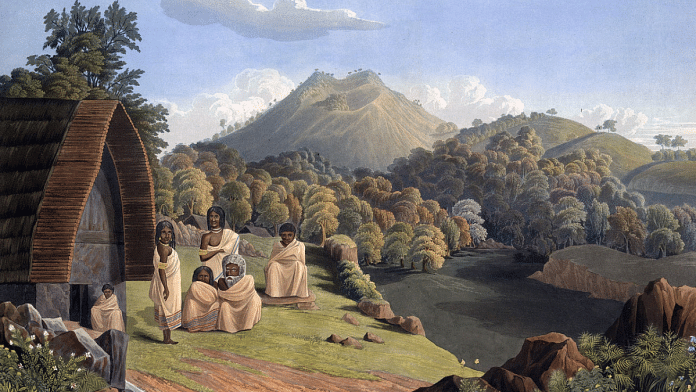

Like many of us, I grew up imagining the Nilgiris as an idyllic place—a honeymoon destination, with rolling meadows and fields of purple flowers in which tahr and gaur frolicked. But a few weeks ago, at the Ooty Literature Festival, I fell down a deep rabbit hole. The Nilgiris, I learned, are one of South India’s cultural crossroads, situated as they are between Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, and Kerala. Marching armies, trading caravans, and refugees have crossed these peaks for hundreds of years, deeply influencing its indigenous people.

India’s adivasis were a formidable force in its history, with considerable agency. In the Nilgiris, their oral legends reveal both conflict and accommodation with lowland peoples. From the Hoysalas to Haider Ali, many rulers have sought the riches of the hills—but few have successfully retained them.

The long shadow of the state

In 1117 CE, a Jain general by the name of Punisa made an endowment to a three-spired Jain temple in present-day Chamarajanagar in the lowlands just north of the Nilgiri Hills. In his donative inscription, he made the first known claim by a state on the Nilgiris. Punisa had “frightened the Toda, driven the Kongas underground, slaughtered the Polavas, put to death the Maleyalas, terrified king Kala and entering into the Nila mountain offered up its peak to the Lakshmi of victory… he seized Niladri… The ruined trader, the cultivator with no seed to sow, the ousted Kirata with no power left, who had become his servant, he gave them all what they had lost and supported them.”

The “Maleyalas” are Malayalis, “Kirata” is a derogatory Sanskrit term used for forest peoples, and the “Toda” are a pastoralist ethnic group of the Nilgiris. Punisa, in his inscription, claimed to have devastated and routed various peoples and made them Hoysala dependents.

The Hoysalas themselves were former hill peoples of the Western Ghats, claiming the title of Maleparolganda—Man Among the Hill Chiefs—so they probably knew a thing or two about fighting in the hills. While the extent of their control is difficult to verify, this inscription reveals that medieval states saw the Nilgiris as a source of tribute. In his book Ancient Hindu Refugees, a study of the Badaga people of the Nilgiris, Paul Hockings also notes that a fortified medieval trading town was discovered in the hills, possibly established by armed traders trailing Hoysala armies.

This attitude persisted into the early modern period. In her chapter Pepper in the hills: upland–lowland exchange and the intensification of the spice trade in the book Forager-Traders in South and Southeast Asia: Long-Term Histories, Kathleen D Morrison studied how the global demand for pepper made lowland states more assertive in their demands from hill-peoples. In the 16th century, direct European trading contact with India doubled the West’s consumption of pepper to nearly 2,00,000 kilograms per year. Around the same time, according to A Rangaswami Saraswati’s Political Maxims of the Emperor Poet, Krishnadeva Raya, the Vijayanagara Empire became much more assertive in its dealings with various hill and forest peoples. “Increase the forests that are near your frontier fortresses and destroy all those which are in the middle of your territory,” wrote the Vijayanagara emperor in his Amuktamalyada. “Then alone you will not have trouble from robbers!” According to Morrison, Vijayanagara rulers frequently offered tax incentives for the clearing and settling of forests. These moves helped intensify exchanges between hill peoples and lowland states, establishing buffers and intermediaries who extracted forest resources and brought them to cities and ports.

Also read: Odisha’s medieval queens weren’t ‘ideal wives’–they fought off invaders, ordered war & murder

Immigrants and conquerors

The 16th century also saw the arrival of the Badaga people in the Nilgiris. “Badaga” means “northerner” in Kannada, and according to Hockings, the community fled to the Nilgiris in the aftermath of the sack of Vijayanagara in 1565. Correlation, however, is not causation. It is not clear why people in South Karnataka would flee after the sacking of a city in the North, especially when many powerful Vijayanagara lords set up their own kingdoms in the intervening areas. One of these was the kingdom of Mysore, whose feudatories, the lords of Ummathur, aggressively subjugated the Nilgiris in the 16th and 17th centuries.

In her paper Not Isolated, Actively Isolationist: Towards a subaltern history of the Nilgiri hills before British imperialism, Gwendolyn IO Kelly points out that over 36 forts were built at this time in an area of just 500 square kilometres, establishing a tight grip on the hills. While some Badaga legends claim that they fled Muslim officials, many others talk about the extortions of the lords of Ummathur. Hockings notes that one chief was beheaded and dismembered for a late tribute payment and his remains were “bound on poles” from the front to the back of his house. The Ummathur lords imported craftspeople to their forts in the Nilgiris, who later joined the Badaga community.

Other Nilgiri peoples also preserve legends of state interference. The Todas, according to Kelly, seem to have formed a kingdom (to fight off the invaders?). Unfortunately, their king and queen were defeated by Ummathur. Kelly also narrates Toda legends that preserve memories of “Tamilians” raiding uplands, dispersing their sacred buffaloes and demanding tribute for their safe return. It is possible that these raiders were in the employ of Nayaka kingdoms, set up by Telugu warlords in present-day Tamil Nadu around the same time as Mysore and Ummathur were growing in southern Karnataka. Later Mysore rulers—including Haider Ali and Tipu Sultan—clashed with the rulers of Tamil Nadu over control of the Nilgiris and similarly looted the Todas and Badagas. The Nilgiri Hills, then, played an important role in the geopolitics of early modern South India.

Also read: Buddhism has just been reduced to anti-Brahmin thought. But it shaped Hindu reforms too

Having said all this, the people of the Nilgiris were not helpless bystanders and frequently fought back or tried to avoid lowland states. In his chapter Gender and social organisation in the reliefs of the Nilgiri Hills, part of the edited volume Forager-Traders cited above, Allen Zagarell studied memorial stones raised to elite men and women in the 16th and 17th century Nilgiris. He found thematic similarities between stones in the upper and lower Nilgiris, with one notable exception: Armed women are sometimes depicted in the highlands. This prompted Zagarell to argue that upland communities, having much sparser populations, armed their women to fight off raiders from the lowland. And Kelly argues that the older societies of the Nilgiris, such as the Todas, encouraged the Badagas to settle in the region as traders and intermediaries with lowland states—just as lowland states had once established buffers between themselves and forest peoples.

Over centuries, this led to a rich tapestry of relationships between the peoples of the hills. We’ll have more to say on this in future editions of Thinking Medieval.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of Lords of the Deccan, a new history of medieval South India, and hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti. Views are personal.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval‘ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)