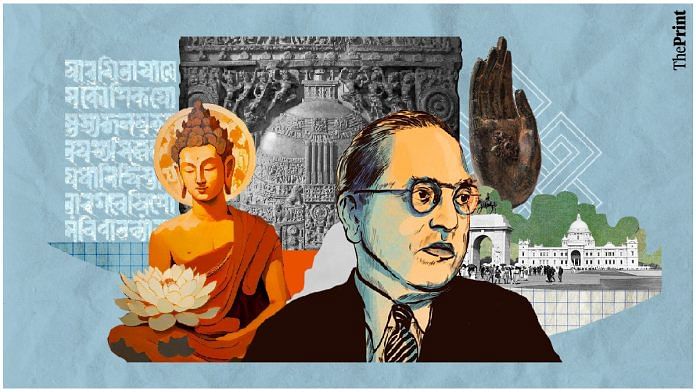

What happened to Buddhism in the land of its birth? To colonial officials, the answer was straightforward: it had been forgotten by degenerate, superstitious medieval Indians. To Jawaharlal Nehru, it had been absorbed by an accommodative Hinduism. To BR Ambedkar, it had been violently extinguished by Brahminism.

The right answer to the question is “all of the above”, but also, in a way, none of the above. Buddhism retained a following in South India well into the 17th century and was remembered for centuries as a dangerous, powerful rival of Brahminical thought. Its colonial rediscovery was revolutionary, influencing generations of political and intellectual leaders in the lead-up to India’s Independence and thereafter.

Dominance to insignificance

As late as the 4th century CE, Buddhist stupas were the most impressive buildings to be found anywhere in South Asia. Especially along the Andhra coast, Buddhist establishments such as the Great Stupa at Dhanyakataka—known as the Amaravati Stupa today—stood hundreds of feet tall and attracted donations from royals, monks, merchants, warriors, and craftspeople. Monastic interest in commerce encouraged some of the earliest urbanisations in the Deccan region as well as the Andhra coast.

At the ancient citadel of Nagarjunakonda—the site of today’s Nagarjuna Sagar dam—the kings of the Ikshvaku dynasty built small temples of Vishnu and Shiva, but they were eclipsed in size by the Buddhist stupas and monasteries patronised by their queens. Historian Mekhola Gomes’ essay, “Decentring the King: Kinship, Identity, and Power in the Ikṣvāku Kingdom”, explores this dynamic.

But something changed, quite drastically, by the 7th century CE. Preferring Shaivite rituals and metaphysics, as well as the ideological support offered by Brahmins, a wave of new dynasties rose across the subcontinent, reducing Buddhism to near-insignificance. Brahminical thinkers and singers mounted a series of verbal (and possibly physical) assaults on Buddhist strongholds and cornered royal largesse. Buddhists responded in kind. In Bengal and Lanka, Buddhist institutions retained enough support to survive and adapt to the times; in present-day Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu, they faded. But they did not entirely disappear.

The great Chola port of Nagapattinam in today’s Tamil Nadu, for example, was home to an impressive stupa in the 11th century, built by the king of Srivijaya in present-day Indonesia (or possibly Malaysia). The stupa was, according to a donative inscription, published in the edited volume Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa: Reflections on the Chola Naval Expeditions to Southeast Asia, “of such high loftiness as had belittled the Golden Mountain [Meru]”. It was probably used by diaspora merchants, but also by a local Tamil-speaking community.

In her article “Nagapattinam Bronzes in Context: Cultural Routes and Transnational Maritime Heritage”, archaeologist Himanshu Prabha Ray notes that hundreds of Buddhist bronzes were discovered in excavations there. Mobile ritual bronzes were a Shaivite innovation: clearly, these local communities shared practices with their Shaivite neighbours. Tamil inscriptions in Chola-controlled Sri Lanka reveal that South Indian Buddhists even donated animals and ever-burning lamps to the Buddha, just as Shaivites did.

Also read: Rise and fall of Indian Buddhism was a stranger, more exciting process than we know

The long ‘afterlife’ of Buddhism

Even in regions that no longer had active Buddhist communities, the memory—and political utility—of Buddhism loomed large. In his chapter “Dhanyakataka Revisited: Buddhist Politics in Post-Buddhist Andhra”, part of the edited volume Buddhism in the Krishna River Valley of Andhra, historian Jonathan Walters studied inscriptions made by a 12th-century local king, Keta II of the Kota dynasty. The Kotas ruled from an ancient fort in present-day Amaravati in Andhra Pradesh, once linked to the trading establishments anchored in the Great Stupa.

Many centuries after the Great Stupa was abandoned, the city was still considered sacred. Its new religious centre was the temple of Shiva Amareshvara—which, as Walters notes, featured coping stones from the Stupa in its foundation. (Indeed, the name Amaravati derives from the city’s Shaivite history, and is not Buddhist). The Shiva linga itself was a 15-ft tall pillar of white limestone, possibly from the Stupa. Similar lingas can be found in other medieval Shiva temples in Andhra Pradesh, including those at Draksharamam and Samarlakota. This sort of architectural reuse—whether a result of religious hostility or respect—is not uncommon in South Asia.

King Keta II’s coronation in 1184 was accompanied by unorthodox rituals. His court made significant endowments to Brahmins and to Shiva Amareshvara, but also gave Chola-style ever-burning lamps and animals to a Buddhist statue. This was brought to the temple from the Great Stupa; the endowments were recorded on pillars, which were also taken from the Stupa. The Buddha was described in these endowments as Sugata, “Well-Gone-One”, a name going back to the earliest practices at Amaravati, Walters notes. And Keta creatively had another inscription made in archaic-looking letters, describing a legendary king-of-kings who stopped at Amaravati, took permission from the Shaivite deities, and made endowments to the Buddha in his residence at the Stupa.

All these amount to a respectful appropriation of the city’s Buddhist past, supporting Keta II’s own claims of being a king-of-kings. Indeed, one of his allies—the Lankan king Parakramabahu I—was Buddhist. However, as Walters shows based on Lankan texts, ties between the island and Amaravati persisted well into the 1300s. The powerful Buddhist pontiff Dharmakirti visited it then and performed a magnificent ceremony. He anointed Keta II’s appropriated Buddha statue with scented paste and flowers, and bathed it in sesame oil, milk, and water.

At the same time, another important Lankan lord, Sena Lankadhikara, built a stone temple to the Buddha in Kanchipuram. The latter, at least, indicates that Buddhist communities were still important in parts of South India. Indeed, as late as the 1500s, the Vijayanagara emperor Krishna Raya ordered the restoration of properties to Buddhist establishments in Tamil Nadu. And in Nagapattinam, Buddhist bronzes were produced into the 1600s.

Also read: What we know as Indian Buddhism today was shaped by Central Asians and Greeks

The ghost of Buddhist intellectuals

As part of my research for this column, I also read Douglas Ober’s Dust on the Throne, a thrilling account of the “rediscovery” of Buddhism by colonial archaeologists and nationalist intellectuals in the 19th and 20th centuries. Ober points out that even in Northern India, where Buddhist communities essentially vanished in the medieval period, they remained very much alive in texts.

In some, like the Bhagavata Purana, they were depicted in conciliatory terms, with the Buddha appropriated as an avatar of Vishnu who tried to protect humanity from ignorance. In others, the Buddha instead introduced his doctrines to demons to weaken them, drawing them away from the “true” path of Vaishnavism. Many texts warned upper-caste Hindus to avoid socialising with Buddhists. From the 8th to the 14th century, Buddhist arguments were reproduced and refuted by Brahmin authors, and they continued to be remembered (hazily) well into the 18th century. Buddhists remained the stereotype of the anti-Brahmin, the heretic.

When a Buddhist refutation of caste was rediscovered and published by British official Lancelot Wilkinson in 1839, his collaborator, Pandit Subaji Bapu, wrote a long, furious rebuttal. History, it seemed, was beginning to repeat itself with this rediscovery. Ober comments: “For the first time in several hundred years, that great heretic, the outstanding dissenter, and foremost ancient challenger to Brahminical orthodoxy, was returning to the public sphere.” In subsequent decades, Buddhism—or perceptions of Buddhism—would shape not only Hindu reform movements but also nationalism and Dalit politics. Despite all its travails, the ancient religion still stands today.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of Lords of the Deccan, a new history of medieval South India, and hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti. Views are personal.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval‘ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)