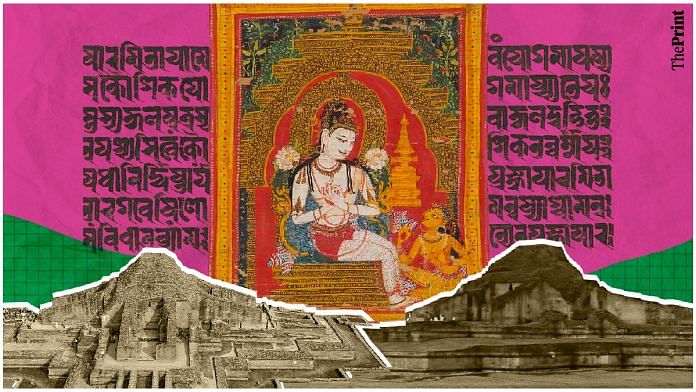

The decline and fall of Indian Buddhism was as complex a process as its rise. Perhaps no site exemplifies this as well as a great stupa-temple and monastery that today lies neglected in northern Bangladesh. Known as the Paharpur Bihar today, it was once called the Great Monastery at Somapura and profoundly shaped both the religious and political history of Eastern India.

The greatest monastery you’ve never heard about

Though generally outshone by its contemporary, the Nalanda mahavihara (Great Monastery), Somapura—as historian Sanjukta Datta writes in Building for the Buddha (2019)—is the single largest Buddhist monastery ever discovered. Its origin was the result of protracted State formation processes in the Bengal region (by which I refer to both West Bengal and Bangladesh). This historic geopolitical territory was composed of smaller units, studied by Professor Ryosuke Furui in Buddhist Viharas in Early Medieval Bengal (2021). The northern portion, known as Pundravardhana, was linked to Bihar, historically a great urban and State centre in northern India. The southern region, comprising the Bengal delta and the regions bordering present-day Myanmar, was a flooded, muddy, mangrove-dense terrain that would only be tamed by new labour mobilisations in later centuries (Furui 2021, page 101).

As early as the 5th century, the Gupta Empire of the Gangetic Plains had governors and officials in northern Bengal or Pundravardhana. Soon after the collapse of the Gupta State, the fertile region was repeatedly raided by warlords, finding itself on the frontier of other, more secure kingdoms. This came to an end with the rise of a new imperial formation in Bengal: the Pala Empire. By the late 8th century—around the same time as Buddhism had been subordinated in older centres like Kashmir—the Pala State had successfully subdued much of the wild Bengal frontier. Next it erupted into the Bihar region, which still had many major Buddhist sites, and began a protracted geopolitical struggle to take control of the Gangetic Plains. To legitimise themselves, they made gifts to older sacred sites, including those at Bodh Gaya and Nalanda. Much more significantly, they also commissioned mahaviharas across their territory, including those of Vikramashila and Odantapuri, as well as Somapura. A number of seals discovered at Somapura bear the inscription Śri Dharmapāladeva Mahāvihāriya Ārya Bhikshu Saṁghasya, “belonging to the Noble Order of Monks of the Great Monastery of the Auspicious Lord Dharmapala”. Dharmapala was one of the most powerful of the early Pala kings, and Somapura was built at a corresponding scale.

A 1999 reconstruction by Bangladeshi researchers suggested that at Somapura’s centre was a colossal stupa 70 feet tall situated on terraces, surmounted by a curvilinear superstructure. Symmetrical on four sides, this would have resembled a gigantic four-sided savatobhadra (“Auspicious on All Sides”) Hindu temple, its power emanating into the cardinal directions like a mandala (a sacred geometric diagram representing the cosmos). The brick core was decorated by friezes of carved stone. Surrounding this was a field of nearly a square kilometre, which had dozens of smaller structures, some of which have since vanished. This was enclosed by a wall with hundreds of cells for monks. All this already comprises the single largest Buddhist monastery discovered, but the mahavihara actually extended beyond these walls. Its actual extent is still unknown and awaits further excavation.

Also read: What we know as Indian Buddhism today was shaped by Central Asians and Greeks

The Buddhist monastery as an imperial centre

These mahaviharas were powerful economic, ritual and political centres. Here monks studied and copied out Buddhist scriptures, which were no longer in Pali, Prakrit or Gandhari but in Sanskrit, by now the premier language of power in South Asia. Bronze and stone idols of Gautama Buddha and future Buddhas (bodhisattva) were offered libations of milk and scented water. Fragrant incense was burned, and sumptuous textiles were used; at least in a practical sense, the medieval Bengali monastery was quite similar to contemporary Shaivite monasteries in central India. Buddhism scholar Ronald M. Davidson writes in Indian Esoteric Buddhism (2002) that these medieval monks behaved practically like the kings-of-kings who were their patrons. They underwent ritual consecrations, established smaller viharas as vassals to their mahaviharas, and even maintained their own armed forces to administer justice and protect their possessions: land, gold, texts, and artefacts. Even the structure of Somapura, resembling the emanation of divine or royal power into the four directions, suggests that it saw itself as an imperial centre within an imperial centre.

Its semi-divine monks had a complex relationship with society and polity at large. At an early stage, they acted as integrative sites for the Pala State. For example, as Professor Furui writes in Land and Society in Early South Asia (2020), Pala vassals made donations to the Somapura mahavihara to ingratiate themselves with their overlord, its founder. In the late 8th century, the vassal lord Bhadranaga set up a perfumed chamber for worship in Somapura, and assigned a village he owned to support it. Bhadranaga himself was not based in northern Bengal but had extensive landholdings here in the heartland of the Pala State (Datta 2019, page 6). By assigning his village to a mahavihara, he made it effectively tax-free and “legitimately encroached upon the royal power” (Furui 2020, page 144).

The growing power of such vassals eroded the revenue base of the Pala State, which was already strained by its wars in the Gangetic Plains. From the 9th century in northern Bengal, the Pala kings no longer made grants to Buddhist institutions, instead preferring to patronise Brahmins who could offer royal ritual services. Land grants from vassal lords also disappeared as the State sought to consolidate its landholdings. (Datta 2019, page 6). But major changes were afoot: catalysed by Pala State formation in northern Bengal, southern Bengal was now emerging as a new agrarian and State centre. And other States had taken note of the waning of Pala supremacy.

Also read: India’s Buddhist nuns you don’t hear about: Landladies, loan sharks, merchants

Somapura’s apogee—and end

By the 11th century, the monks of Somapura had achieved wonders. In its ruins have been found “inscriptions, coins, seals, [and] images of bronze [and] stone,” writes historian Monalisha Laha in Some Selected Buddhist Monasteries as Centres of Learning of the Pala Period (2015, page 142). Somapura’s senior monks, endowed with its resources and their own, even set up shrines and images in older monasteries, such as at Nalanda.

But the fortunes of the Palas, their erstwhile patrons, were also tied to Somapura. The same 11th century saw a series of compounding military disasters for the Palas: first the armies of the Chola emperor Rajendra I defeated and raided them in 1022–1023, setting up the Sena dynasty as his vassals in the region. Then by the middle of the century, the militant central Indian king, Lakshmikarna of the Kalachuri dynasty, elbowed his way into urbanising Southern Bengal, setting up his own vassals, the Varman dynasty, in the region called Vangala. Lakshmikarna, like other kings of his dynasty, was closely tied to the monks of the Shaivite Mattamayura order, who now appeared in Bengal in large numbers. The sun of Indian Buddhism was at last setting, over one-and-a-half-thousand years after the Buddha achieved his enlightenment under the bodhi tree. At this stage, the decline had little to do with Turkic raiders half a world away; it was driven by local dynamics, both religious and political.

A rather sorrowful inscription was commissioned in Nalanda soon after, studied by historian Bedasruti Bhattacharyya in Varman’s Incursion and Sacking and Burning of Somapura Mahavihara (Varendri) (2012). Bhattacharya translates: “In the illustrious Somapura there was the ascetic, Karunasrimitra… Who when his house was burning, (being) set on fire by the approaching armies of Vangala, attached (himself) to the pair of lotus feet of the Buddha (and) went to heaven.” Trapped in the looted, burning ruins of Somapura, the monk died clinging to the shattered fragments of the world he had once known.

The declining Palas had no interest in Somapura’s upkeep now. Even smaller lords, who had once made gifts to it, were more interested in making their own mahaviharas in the ruins of the Pala State. And a century away loomed the power of the Delhi Sultanate and its successors, who reoriented the region’s agrarian networks further away from its medieval monasteries. All that remains of their dramatic history now are silent ruins of brick, in which the chants of forgotten monks faintly echo.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of Lords of the Deccan, a new history of medieval South India, and hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti. Views are personal.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval‘ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)