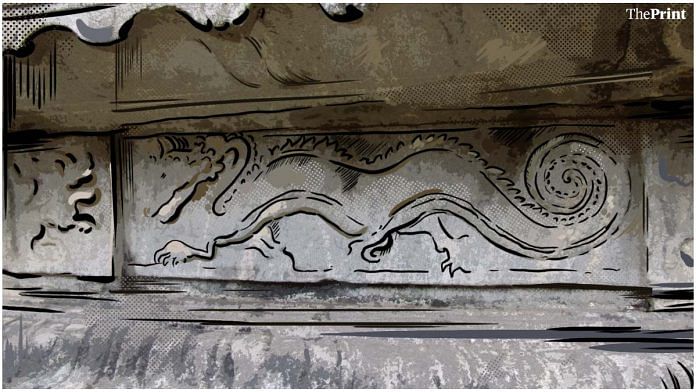

In a quiet Jain temple in Moodbidri near Mangalore, Karnataka, constructed around 1430 CE, are some carvings that one would never expect to see in a temple. A sinuous dragon unfurls along the plinth. On the pillars of a hall in the compound are somewhat uncertainly carved giraffes. These are a far cry from the myths, gods and dancers typically seen in such temples.

So how did the grandees of this South Indian town see dragons and giraffes in the 15th century—and how did they come to end up in this shrine? The answer lies in medieval globalisation.

Africa and food crucial to Indian trade

While many of us have heard—at least in passing—of Indian interactions with Southeast Asia and China, or perhaps even Arabia, Africa is a gaping hole in how we think about premodern trade. The vast African continent, much like premodern India, was home to a dizzying array of societies and polities. Its east coast, dominated by Swahili-speaking cities and kingdoms, has traded intensely with the subcontinent for over a thousand years, exporting ambergris, ivory, leopard skins and tortoiseshell while importing textiles, jewellery, and spices. Another major item imported was Chinese ceramics—a trade that was dominated by Indian merchants, especially Gujaratis, with communities attested in Malindi, Mombasa, Kilwa, and Pate in the 15th century.

Though the Swahili coast was predominantly Muslim—having converted under Arab cultural and economic influence by the end of the first millennium CE—India played an enormous role in its trading activities and even its food. Phillipe Beaujard notes in The Worlds of the Indian Ocean that the Indian zebu cattle was the ancestor of many extant African breeds, and domesticated plants such as hemp, sesame and pigeon pea arrived in Africa from India. Even rice was exported in massive quantities to the Swahili coast —Mangalore was one of the major hubs of Indian rice trade with Africa and West Asia. Indeed, Mangalore and nearby ports in the South Kanara region (comprising the southwest coast of present-day Karnataka) would emerge as one of the great hubs of Indian Ocean trade by the 15th century.

A combination of factors led to this emergence of south Kanara as a global commercial hub. Earlier Deccan empires—such as those of the Rashtrakutas—were centred in north Karnataka, and directed their trade through the Konkan coast. However, in the 15th century, the metropolis of Vijayanagara, rapidly becoming one of the largest cities in the world, acted as a great centre of consumption, pulling in Indian Ocean goods through the Mangalore gap of the Western Ghats.

Mangalore also emerged as a centre of pepper production, challenging the dominance of the Malabar coast; it was also Vijayanagara’s main port for the import of warhorses. Nearby Bhatkal exported powdered sugar and coconuts across the Western Indian Ocean. By the 16th century, the poet Kanakadasa wrote in his Mohanatarangini that “the wealth of those that trade in agricultural products with foreigners was such that they can lend money to [the god] Kubera, and they sit with piles of gold and money in their shops.”

Also read: Instead of trying to beat China in Sri Lanka, New Delhi needs to change the game

China and a “beastly diplomacy”

With the emergence of the Ming dynasty in China in the late 14th century, a powerful new force entered the world of the Indian Ocean. Seeking to legitimise his usurpation of the throne, the Ming Yongle emperor (r. 1402–1444) sent out a series of massive naval expeditions under Zheng He, a Muslim Yunnanese admiral. Professor Tansen Sen notes in a 2016 paper that the expeditions consisted of hundreds of ships carrying thousands of troops from all across China and the Indian Ocean, and led to a surge in the circulation of peoples, goods, and, oddly enough, animals.

Across the vast world of the Indian Ocean, Zheng He and the Ming court set out to rework economic and political networks in a hierarchy with themselves at the top. Javanese and Indonesian rulers were replaced and threatened to toe the Chinese line and provide tribute; a Sri Lankan king was captured and Buddhist relics seized; the emerging Malabar city of Kochi was declared a Ming vassal state, raising its status against its aggressive rival, Kozhikode. But alongside all this, Zheng He also brought spectacular treasures to trade with friendly polities, especially porcelain and silk, and enormous quantities of gold and silver. Rulers and traders across the Indian Ocean took notice, sending diplomatic embassies back with the Ming admiral, carrying their most exotic goods to impress the Chinese and secure trading agreements.

Giraffes were among the most important animals that were sent with these embassies. Chinese officials considered them auspicious, divine beasts that legitimised the Yongle emperor. Soon, the African state of Malindi sent one; some were sent by Aden on the Red Sea coast; one came from Arabia; one from Sumatra; and some from the Sultanate of Bengal. All these animals must have been captured by experts in Africa on behalf of these polities, a sign of just how deeply integrated Indian Ocean commercial networks had become. The giraffes, notes professor Sen in Cargoes in Motion: Material and Connectivity Across the Indian Ocean, were also living, breathing examples of the goods that these diverse polities could offer to China, and their ability to confer prestige on the emperor through trade and diplomacy. Happening at a time when India-Africa trade had reached unprecedented levels, it is possible that the merchants of South Kanara either witnessed these animals at port on the way to China, or directly traded with Zheng He’s fleet, perhaps receiving pottery or silk emblazoned with dragons.

Also read: Why did Tamil merchants build Hindu temples in China? Answer lies in commerce

When they commissioned the Moodbidri temple in 1430, therefore, it is unsurprising that they chose dragons and giraffes as sculptures to decorate it. Surely Indian merchants “richer than the gods” should have a temple adorned with the symbols of the vast globalised world that they so successfully participated in.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a writer and digital public humanities scholar. He is author of Lords of the Deccan, a new history of medieval South India, and hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. Views are personal.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval‘ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Neera Majumdar)