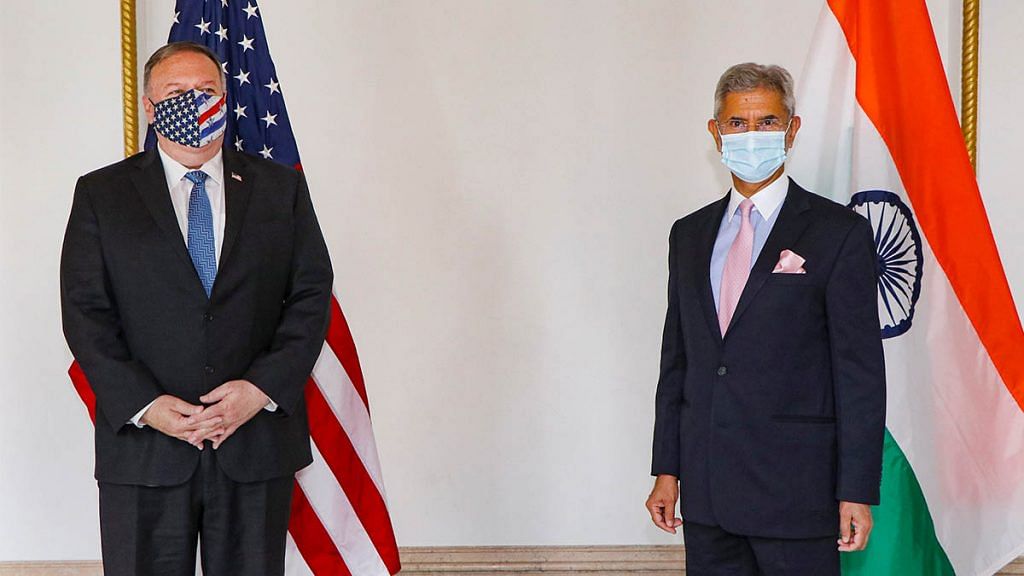

Thumbing his nose at the coronavirus, Foreign Minister S. Jaishankar made his way to Tokyo to attend the meeting of the ‘Quadrilateral’ or Quad, the informal grouping that includes the US, Australia, Japan and India. US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo made no bones about the real focus of the group — building a “true security framework” — adding for good measure that the Quad could counter the threats of the Chinese Communist Party. That statement probably made the others blench. Of the four, not all are yet on the same page, though they’re clearly reading the same book. By annoying everyone, China has made sure of that at least. In Tokyo, India’s Jaishankar was at his blandest, which will lead to critics accusing South Block of pussy-footing on China.

But New Delhi has been busy, and its virtual silence says much about how the Quad is to be played at a time of serious tensions in Ladakh.

Also read: With eye on China, India and Japan discuss strengthening of security ties and supply chains

Checking the economy

An acknowledgement of the economic inter-dependence of Quad members on China was apparent in Pompeo’s next statement when he noted that ‘security’ includes “economic capacity and the rule of law, the ability to protect intellectual property, trade agreements, diplomatic relationships, all of the elements that form a security framework. It’s not just military. It’s much deeper.” That’s not just talk. At the earlier virtual meeting last month, the discussion was on a common approach to 5G technology. India has finalised a pact with Japan in that area, thus denying Beijing one of the largest markets valued at Rs 19,053 billion by 2025, an estimate that doesn’t include the surge in online education and work due to the Covid pandemic. Bilaterally, however, India will sign on to the last ‘foundational’ agreement with the US, on geospatial intelligence sharing (Basic Exchange and Cooperation Agreement), thus completing all the requirements for a muscular defence and intelligence cooperation.

Despite its (over)reliance on trade with China, which at 32 per cent is greater than most, Australia has recently taken up the cudgels against Beijing on several issues including the origin of the novel coronavirus, and banned Huawei. More to the point, it also increased its defence expenditure by a whopping $190 billion with Prime Minister Scott Morrison warning that such regional uncertainty hasn’t been witnessed since World War II and also citing the India-China standoff. Canberra is looking at longer range strike capabilities as well as buying US anti-ship cruise missiles. Meanwhile, it recently joined the UN in condemning Uyghur “re-education camps” in Xinjiang, something India is yet to do. New Delhi has again not invited Australia to be part of its annual ‘Malabar’ naval exercises, partly since it means expending ‘diplomatic costs’ to an exercise that is unlikely to happen anyway at a time of the Covid pandemic. Yet Australia has an important role to play, should the necessity of blocking Chinese entry into the Malacca Straits arise. But the annual AUSINDEX naval exercises ensures operational compatibility in a bilateral framework.

Also read: Why has India’s China policy been such a failure? Question New Delhi’s assumptions first

Japan’s own position after the heady days of Shinzo Abe and his absolute commitment to the whole ‘Indo-Pacific’ idea, is yet to be seen. Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga is said to have been propelled to power with the backing of pro-China Toshihiro Nikai, the long-time secretary-general of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP).

The invitation to Chinese President Xi Jinping to visit Japan – now delayed due to the pandemic – has yet to be withdrawn, despite the fact that tensions continue due to Chinese presence in the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu islands. The Japanese Defence White Paper 2020 expects this to worsen, with Beijing attempting to make its presence permanent — as in Ladakh. Meanwhile, Japan and India quietly signed an Acquisition and Cross Servicing Agreement — essentially a mutual military logistics pact — that extends the Japanese navy’s possible operations into the Indian Ocean.

Also read: India-Australia’s growing partnership built on military ties and concerns about China’s rise

Delhi on the job

Foreign Minister Jaishankar’s bland statement at the Quad meeting said precisely nothing. But consider this. New Delhi is quietly forging strong military ties, particularly naval ones, with Quad members on a bilateral basis, while keeping the language of Quad itself vague in the extreme, and thus avoiding an increase in tensions with China. But India is still keeping all its irons in the fire.

Alongside, there is the Indo-Pacific Oceans Initiative – referenced in Jaishankar’s statement – which was launched at the East Asia Summit 2019, and includes maritime security in its charter. New Delhi invited Vietnam to be a part of it, even as Hanoi considers filing an international arbitration case against Beijing in the South China Sea. Both will be non-permanent members of the UN Security Council next year. Vietnam, together with New Zealand and South Korea, was also part of an online ‘Quad plus’ meeting earlier. All are countries sitting on important sea lanes. As Pompeo observed, the Quad has an expansion plan, and it seems New Delhi is already on the job.

At a time when the Chinese are digging in opposite Ladakh, India seems to have realised that the Quad can only be of value in a crisis if – and it’s a very big if – it can effectively interdict Chinese shipping across the Malacca Straits, particularly since Beijing depends on the sea for 80 per cent of its oil imports. New Delhi can’t be sure of anything at this stage, which is why it’s firing up its missiles and buying aircraft, guns and munitions from the weapons market. In war, reliance on ‘friends’ is foolhardy.

But it’s nice to have that ace in the hole, gambling on the fact that China cannot retaliate against everybody at the same time. As to whether that threat is working, there is the fury of the Chinese Foreign Ministry on what it calls a “Mini NATO”. Whether this view suits India’s China playbook is yet unclear, probably even in the Ministry of External Affairs. That’s actually a large part of the problem.

The author is former director, National Security Council Secretariat. Views are personal.