The political compulsion to defend demonetisation is understandable as one of the stated goals – to immobilise black money – came a cropper.

When there’s no trick left to defend a spectacularly failed experiment, blame Raghuram Rajan.

If India’s top policy think tank is to be believed, the reason economic growth faltered last year, reaching 5.6 per cent in the June quarter after 7.6 per cent nine months earlier, had nothing to do with the November 2016 ban on 86 per cent of the country’s cash.

The decline had been in the making since early 2016 because, under Rajan’s governorship of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), the central bank devised “mechanisms to identify stressed and non-performing assets, which is why the banks stopped giving credit to industries,” Rajiv Kumar, vice chairman of state-controlled NITI Aayog, said on Monday.

Kumar’s premise seems to be that had Rajan not forced banks to make a clean breast of their bad loans, they wouldn’t have faced a capital shortfall. What Kumar called the greatest deleveraging of commercial bank credit in India’s history could thus have been avoided.

The political compulsion to defend demonetisation is understandable. Recent central-bank data showed that 99.3 per cent of the currency made worthless was eventually returned to banks. To the extent one of the stated goals of the exercise was to immobilise so-called black money – wealth that dare not join the formal banking system because it’s ill-gotten – the draconian experiment came a cropper.

The opposition Congress Party, meanwhile, had always claimed that the ill-conceived move, as well as causing immense direct hardship, also cratered the economy. With general elections due next year, officials therefore have to help the government deal with the charge that it sacrificed two percentage points of economic growth for … nothing.

Hence the impulse to shift the blame to Rajan.

Leave aside the problematic idea implicit in Kumar’s argument that it’s somehow wrong for a banking regulator to make banks tell the truth. Focus instead on his factual claim about corporate deleveraging.

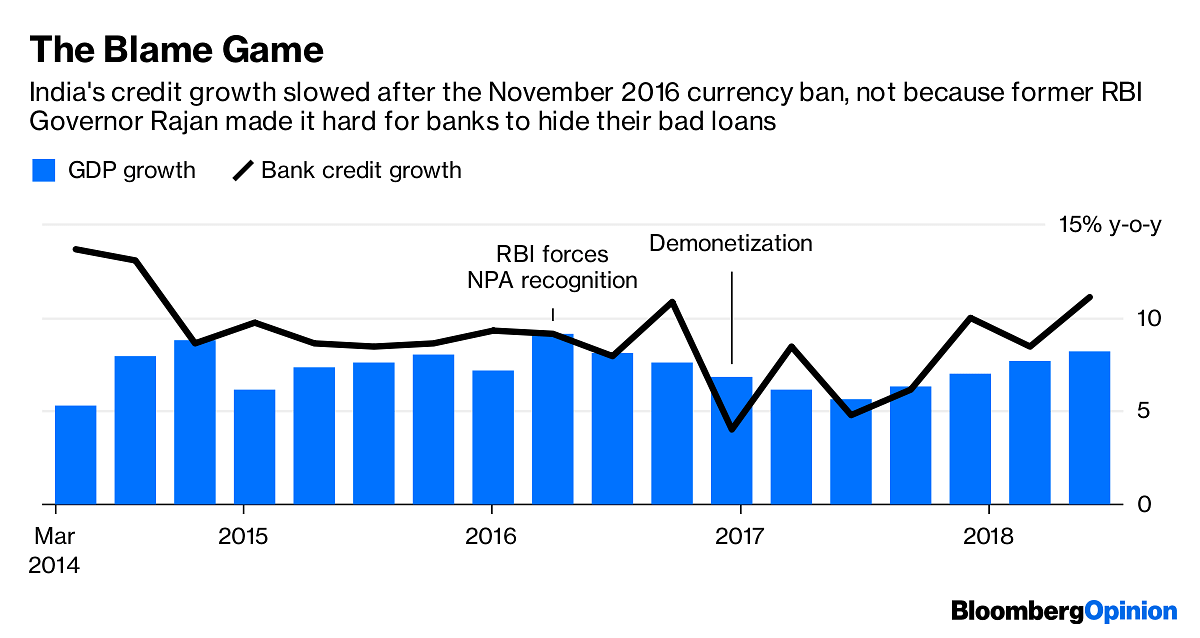

It happens that during the quarter that ended in September 2016, which is when Rajan abruptly left the RBI after one term, commercial credit by Indian banks expanded by 10.8 per cent, the fastest growth in more than two years. The next quarter, after Prime Minister Narendra Modi outlawed most of India’s cash, credit growth slowed to 4 per cent. After a dead-cat bounce it stayed depressed for most of last year.

Kumar could well have argued that India’s new GDP data are too unreliable to conclude that demonetisation did cause a two-point slowdown. It would have been impossible to prove him wrong. But if deleveraging is his story, then banks’ pulling back the supply of credit doesn’t wash. It’s more plausible that demand for credit slowed last year after the note ban – followed quickly by a botched goods and services tax – disrupted supply chains, hitting small businesses and exporters especially hard.

As for the charge that Rajan pushed India into an abyss of deleveraging, some state-run banks may have become zombies, but the market hasn’t stood still.

Specialist lenders like AU Small Finance Bank Ltd., which received licenses under a category started by Rajan, are taking over retail credit. They’re packaging and selling loans to state-run lenders, which still have large branch networks and deposits. Securitisation markets wobbled last year after micro-finance loan portfolios were hit by demonetisation. But with cash coming back into the economy, transactions doubled in the June quarter.

Even if the Modi government never admits that its war on cash was an all-round disaster, to use Rajan as a scapegoat is more than a little silly.- Bloomberg

The rush to produce Demonetization a failure lacks data to back up its claims. The simply attribution of “Return of cash” to the RBI to claim Demonetization was a failure is absurd since the only real metric to decide the consequences of demonetization would be to notice the trend of tax compliance and fiscal inclusion in society. In that regard, the claim that demonetisation was a failure because the amount of cash returned to the RBI reached 99.3% is far from definitive. The Govt claims of destroying 3lakh crore of cash as black money have not come true – but that does not invalidate the rise in tax compliance , the growth of financial inclusion and the resurgence in rule of law.

I partly agree with the author. Mr. Rajiv Kumar’s comments are highly inappropriate. However, criticism of demonetization has to be factual and data-based. Blatant exaggerations such as demonetization having wiped out the entire MSME sector are totally unfounded. In India, the MSME sector ( Micro, Small & Medium enterprises) constitutes a vast network of over 63 million units and employs around 111 million people The share of MSMEs in total GDP is around 30 percent. About 97 percent MSMEs operate in informal sector and their share in gross output of MSME is about 34 percent As per National Accounts Statistics, 2012, the share of informal sector manufacturing MSMEs in total GDP is around 5 per cent. Now, had 30 per cent of the GDP been totally wiped out by demonetization, what could have been impact on the GDP? Even at its bottom pit, the GDP grew by 5.7 per cent in the quarter ended June 2017.

Another thing. Correlation between piling up of NPAs and demonetization is rather thin. Let us take the case of MSME sector, the most vulnerable sector according to critics of demonetization. MSMEforms just around 1.6 per cent of total credit by the banking sector. There was deceleration in MSME credit in the 2014-16 ( prior to demonetization ). This was due to slowdown in economic activity, rising NPAs and reclassification of food and agro-processing units from MSME segment to agriculture sector. Decline in bank credit to MSME sector due to demonetization was observed. However, as per Mint Street Memo no. 13, overall MSME credit cards and especially micro-credit to MSMEs shows a healthy rate of growth in recent quarters. In contrast, MSME exports were affected more adversely by issues related to GST implementation than demonetization due to delay in refund of upfront GST and input tax credit affecting cash driven working capital requirements. Thus the MSME sector is thriving again, though it received a set back due to demonetization. Its felt that the critics of demonetization are unduly inflating the cost of demonetization, may be due to political reasons.

Absolute illiterate view of the person who is incharge of NITI Ayog. If this is what a transformation institute is, only god can save the India.

Rajiv Kumar has to get back and learn his economics again.