When the global economy resumes function in the post-pandemic world, rising India’s economic growth story is expected to return. The International Monetary Fund estimates India’s Gross Domestic Product — GDP — to grow at 1.9 per cent for the fiscal year ending 31 March 2021 — making it the only other major economy alongside China estimated to grow — and has revised GDP growth for the next fiscal year at 7.4 per cent.

Optimism surrounding India’s growth has mainly centred on the domestic propensity to consume, availability of low-cost and plentiful labour, the sharp decline of global oil prices, and the expectation of foreign capital moving to emerging market economies once global macro-economic indicators stabilise.

India’s growth is also likely to be supported by the flight of capital from China.

Despite promising indicators, India’s ability to attract foreign direct investment (FDI) should not be taken for granted — particularly by policymakers in New Delhi.

Also Read: There’s no ‘How to revive economy after Covid’ playbook. But Modi’s India can have an edge

Investment in India

Global companies that once thrived on the efficiency and low costs of Chinese production have begun seeking supply-side diversification and resilience. This trend was set in motion by the tariff war between China and America, and is likely to accelerate in the aftermath of Covid-19. As per the US-India Strategic and Partnership Forum, 200 American corporations had already sought to move their manufacturing bases from China to India in mid-2019. More recently, reports from South Korea and Japan suggest that their firms have also evinced interest in migrating towards production-conducive economies like India, Vietnam and Thailand. Wistron, a Taiwan-headquartered manufacturing partner for Apple, has set aside one billion dollar for expansion in India, Vietnam, and Mexico to address supply chain risks emanating from China. Further, India’s large domestic base of consumers is a potent differentiator compared to other regional competitors, who are primarily export-oriented in their production.

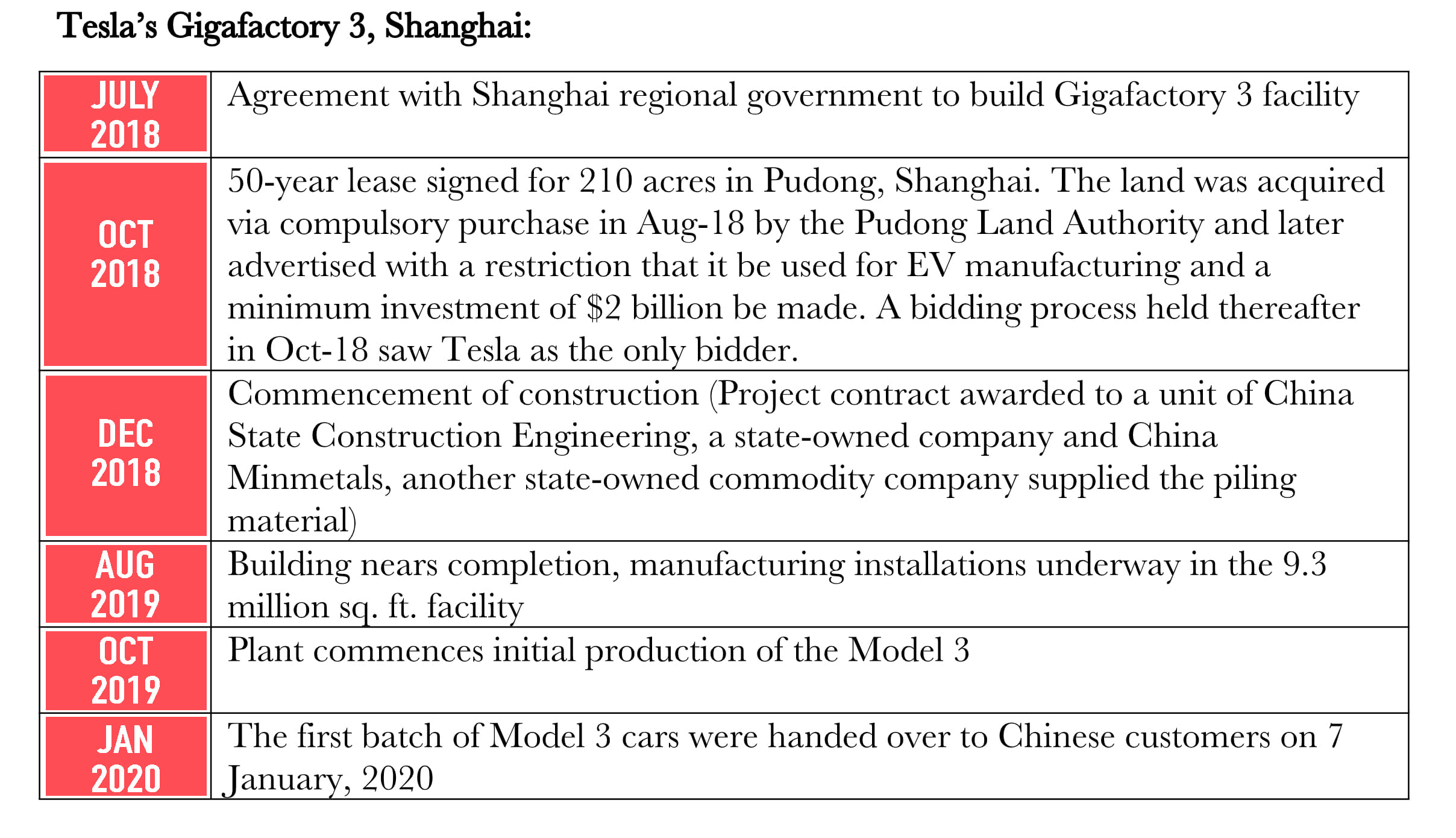

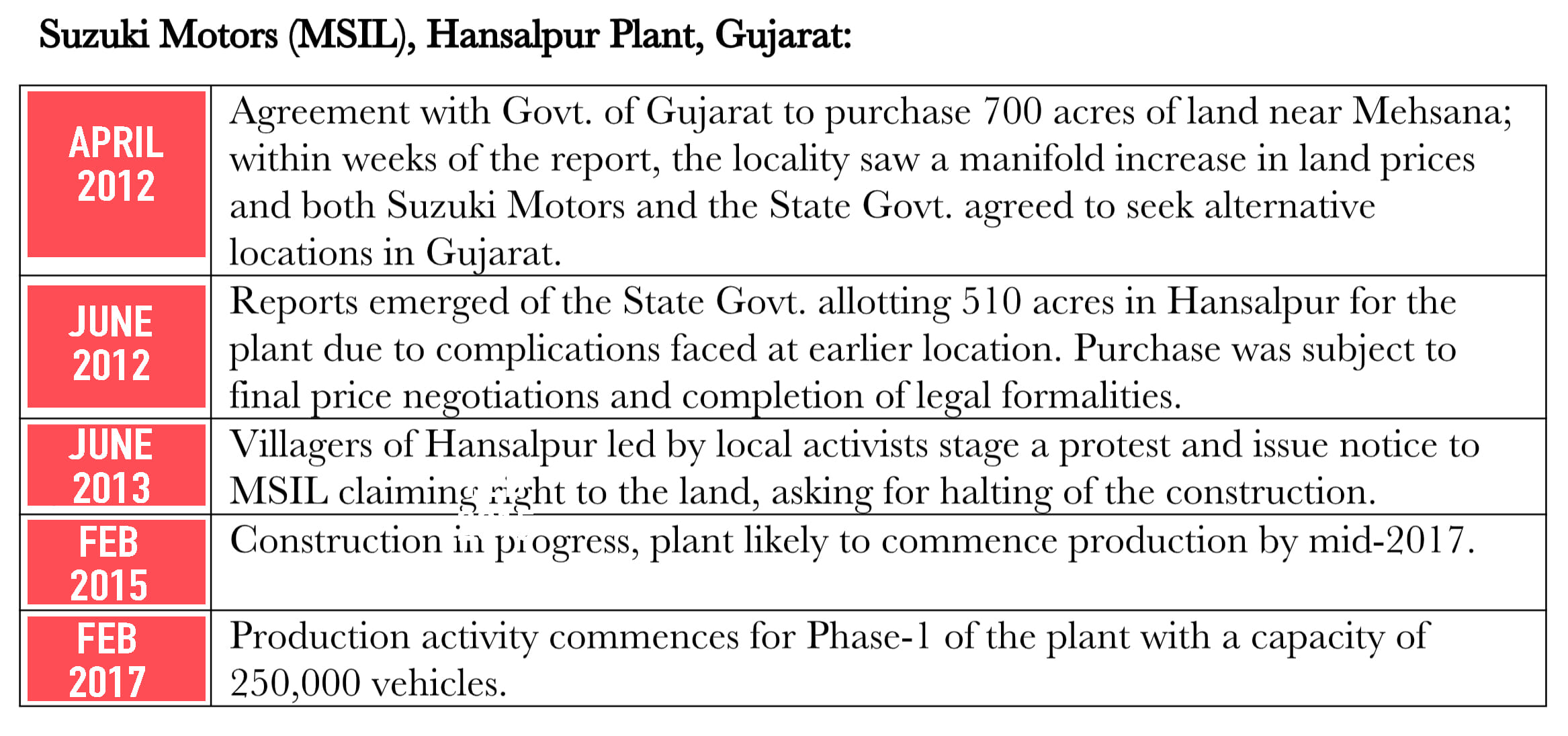

At the moment, all of India’s attention — rightly so — has been focused on lowering interest rates through adjustments in monetary and fiscal policy. However, in the long-run, India will need more in terms of legislative reform if it is to come good on its promise as the “world’s fastest growing large economy”. To understand one of the key issues foreign businesses face in India, it is instructive to begin by comparing Tesla’s Shanghai Gigafactory setup to an automotive plant set up in Hansalpur, Gujarat by Suzuki Motors. Their timelines are as follows:

A mere 537 days separate the agreement with the Shanghai government and Tesla’s first car delivery to customers. Tesla’s capital expenditure was also reportedly 65 per cent lesser per unit of manufacturing capacity compared to the Model 3 production system in the USA. On the other hand, Maruti Suzuki India Limited’s (MSIL) facility took nearly five years from agreement to production and was constrained by multiple externalities. The facility was also on a smaller land parcel and constructed at a location that was not MSIL’s first choice. Although some portion of the five-year period may be linked to internal constraints, challenges like speculative increase in land prices and local agitations remain primary culprits. Moreover, MSIL’s setup was in Gujarat, which is among the top three industrialised states in India. Lower ranking Indian states in the industrial index — where the bulk of the low-cost labour resides — maybe even further away from what are acceptable timelines for establishing manufacturing units.

Also Read: Investment a must to become global power, new FDI rules can’t protect India’s interests

The land promise

For India to deliver on its promise, reform on land laws is vital. Access to technical expertise and financial capital is more easily available to foreign investors. However, the stringency of land laws has, so far, prevented the proliferation of commercial activity in the manufacturing sector, and dampened foreign investor sentiment. The current legislative framework for land acquisitions in India is detailed under the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement (LARR) Act, 2013.

The act increased the compensation given to landowners, provided rehabilitation and resettlement services, mandated a Social Impact Assessment (SIA) for public infrastructure projects, and provisioned a consent clause for projects under the private and public-private partnership (PPP) route. While the general intent to bring such a law was understandable, it spectacularly failed to balance the interests of landowners with India’s development needs. As former RBI governor Duvvuri Subbarao highlights, “investors have [since] been frustrated by India’s excruciatingly cumbersome land acquisition laws that result in heavy cost and time overruns.”

The Narendra Modi government attempted to pass an amendment to the principal Act in 2015. The said amendment sought to exempt five categories of projects — (i) defence, (ii) rural infrastructure, (iii) affordable housing, (iv) industrial corridors, and (v) infrastructure including PPPs where government owns the land — from the restrictions imposed by the LARR Act, 2013. This was proposed in order to reduce the minimum time required to complete the land acquisition process from 50 months to 42 months. The bill was passed in the BJP-majority Lok Sabha, but its progress was halted by a unified opposition in the Rajya Sabha. Opposition parties flagged definitional ambiguities and the dilution of statutory protections for landowners (who are mainly farmers in India).

Land being a state subject in India, six states have enacted legislations “exempting or enabling exemption of land acquisition from consent and social impact assessment requirements,” under the LARR Act, 2013. The wider issue of balancing corporate and farmer interests through a national framework for land laws remains. It warrants examination how an electorally conscious government pursues this reform agenda, particularly since it is not realistic to expect any changes in the land acquisition laws related to a downward revision of the scale of compensation or rehabilitation and resettlement. We provide some general suggestions.

Also Read: With FDI move, India can now trade with China from a position of strength

Ways to bring land reforms

First, land acquisition for manufacturing firms should be integrated with local development. LARR Act 2013 increased the compensation for land acquisition from 1.3 times the price of land to twice the price of land in urban areas, and from twice to four times the price of land in rural areas. India already meets global compensatory standards. However, since agricultural land is the primary source of sustenance for most small landowners, the task of rehabilitation cannot be successfully achieved until an alternative mode of employment is provided.

Therefore, for a minimum period of ten years, there should be a 50 per cent reservation for locals in semi-skilled manufacturing jobs, and a ten per cent reservation in skilled or executive positions in all manufacturing firms set up under the land acquisition process. Also, the government should ensure that the transition from agricultural to manufacturing sector for the labour force is eased by setting up on-site vocational training centres in consultation with the manufacturing firms. This will reduce the dependence on the agricultural sector for employment and offer meaningful efficiencies by enhancing availability of skilled and semi-skilled labour to foreign manufacturing companies.

Second, the government must streamline its existing land holdings, and provide incentives for private land banks and public trusts to help set-up manufacturing units with foreign firms. The government of India — across various ministries and sub-divisions at the national, state and district levels — is arguably the largest landowner in India. If the Indian government is able to identify non-productive land under its ownership (including wasteland areas suitable for manufacturing) these could be simpler solutions to the problem of land acquisition for creating public infrastructure.

Additionally, public trusts and private entities in India, who have large portions of unutilised land banks, through tax breaks, long term leases, or land-equity deals, could also be incentivised into the process of facilitating the setting up of foreign manufacturing facilities. This would require each state to update and computerise its land records since most of them still do not have comprehensive accounts of non-agricultural holdings and continue to use Colonial era Land Revenue Codes. The rather expansive definition of “forest” provided in the T.N. Godavarman Thirumulkpad vs Union Of India case in 1996 — which includes areas neither reserved forest nor notified or protected forest – also needs to be revised through periodic land revision surveys.

Third, separate land acquisition tribunals should be set up to expedite legal cases pertaining to land acquisition. Importantly, if the tribunal decides to pass a stay order on any matter, there should a stipulation for consecutive-day hearings and a definite time period within which the case must be disposed of. This would help avoid the potentially significant legal expenditure and time delays endured by foreign manufacturing firms in the course of setting up base in India.

Fourth, the Indian government can introduce temporal and spatial exceptions to the Land Acquisition Act, 2013. First, the temporal exception may be achieved through the ordinance route that the Modi government has previously deployed. For instance, the government could announce a time bound (six month) relaxation of consent and SIA requirements under the 2013 Act for those companies looking to shift their manufacturing units from China to India. Second, for spatial exceptions, the government could introduce similar relaxations in select social economic zones (SEZ) or industrial corridors for these companies.

Fifth, instead of concentrating power under nodal agencies, the government needs to aim at greater e-governance facilities. Discretionary powers in the hands of government functionaries needs to be reduced and the entire process — from getting clearance to purchase land, registering property, getting electricity and water connections, getting environmental clearance, obtaining permission to set up a factory and clearance from pollution control board — should be carried out through a single window digital process. The grounds of rejecting applications should also be clearly spelt out, and the time for acceptance/redressal must also be stipulated. The Modi government has recently announced its intention to use a geographic information system (GIS) based platform to create a digital network of land banks at the national level —akin to the “Gujarat Land Bank Portal” set-up in Jan 2020 — to assist foreign investors in a transparent and competitive digital search for land parcels. It has also proposed an “investment clearance cell” to move all statutory clearance requirements to a single-window platform.

The Indian government’s fascination with the “Ease of Doing Business” rankings has not served it well. While landmark policy reforms between 2014-19 have manifested in a 79-position jump in India’s rankings to 63rd place, these are not fully representative of several on-ground challenges faced by businesses. In fact, Vietnam, which ranked 70th has been more successful in attracting foreign investment.

Incidentally, Vietnam’s performance was the weakest in ‘Resolving insolvency’, a parameter India has extensively addressed via the Bankruptcy Code. India’s strong commitment to democracy and the freedom of information makes it a strong competitor to attract foreign capital in a post-Covid-19 world, and participate more purposefully in the global supply chain. However, the government will have to tackle key issues such as reforms in land laws before these promises can be realised.

Ameya Pratap Singh is a PhD candidate at University of Oxford and Aditya Vora is a chartered accountant. Views are personal.

As always, a nagative and biased protray of i dia.where are yoi located ? Pakistan? China?…

If companies want to i vest in india, they will.its anti indians like you that dnt want india to prosper.i ha e only seen negative articles from you.we indians should boycott this asshile

As always, a nagative and biased protray of i dia.where are yoi located ? Pakistan? China?…

If companies want to i vest in india, they will.its anti indians like you that dnt want india to prosper.i ha e only seen negative articles from you.we indians should boycott this asshile

Its totally an unpredictable and research less article. You didn’t go through the foreign policies precisely, please do research properly before posting anything. You are just discouraging foreign companies to come India.

Why will any industry move to India when it will not have right to hire and fire an employee?.

Amend labor laws to allow hire and fire of labor

No big investors will invest unless you allow investors to hire and fire unwanted employee.

No big investors will invest unless you allow investors to hire and fire unwanted employee. Tax laws be not amended with retrospect effect and last unwanted judicial intervention resulting in undue delay in completion of projects.

Wrong comparison. Compare it with Kia’s Anantpur plant.

April 2017: Kia motors signed a MoU with Andhra Pradesh Government to set a manufacturing plant in Anantpur.

August 2019: Kia motors started production.

So don’t try to mislead and declare by yourself that you don’t want that foreign investments come to India.

With this article, the print is discouraging the foreign investments in India. You barely find any appreciation of govt.’s steps to encourage the Investments.

Only a labour can comment like this

Good article. The Congress and the Communists with their anti-development and anti-wealth creation agenda are always trying to put obstacles in the way of Land reforms. The left in India has always eulogized poverty instead of finding ways to create wealth and eliminating that poverty. Along with land, labor and judicial reforms, India also needs a strong commitment to rule of law free from political leftists appeasement of certain sections of society. There are many areas of India where muslims are the majority where law and order has completely collapsed. During covid-19 lockdown, Islamist people in muslim areas in many cities were pelting stones on Police who were trying to enforce lockdown and on and healthcare workers who were trying to visit the corona virus victims. This is unacceptable. Rule of law should be enforced by force if necessary and muslims or anyone else should not be given any exceptions. The police dont want to use force on Islamists pelting stones because they dont get support from the leftist politicians and media who are quick to point fingers at the police while ignoring the provocations of the Islamists.

aa gai har cheeze m hndu angle dekhne wale..kam s kam topic ka meaning to samajh l bahi…

Than why are you living here go from our lovely Bharat.

Pahla udesh hai musalmano ko to nipatana,dusre jaise sikhs,budh,christians to chutki me niptenge.

Dalit OBC,aur adiwasi to hajaron salo se gulam hai,unse niptna koee muskil nahi.

E sab karna hai vikas ka chola pahan kar

Jab hamare khabo ka desh banega E sab khuda khud ho jayega.

India is wasting time on its anti-muslim propaganda and fanning hindu-muslim fight rather than focusing on development!

Except for this government which is obsessed with event management, window dressing and fake rankings nobody believes in this Ease of doing business. If you need any evidence try starting a business in India. From conception to delivery the path is filled with obstacles. Even aftet things are up and running there is no guarantee that the government will not make a 180 Deg. reversal and go back on all it’s promises. Nobody in their senses will invest in India when far better options are available. India’s huge market is another myth due to widespread poverty which is going to get worse after this pandemic. If I was moving from China, coming to India wouldn’t even be an option.

Because people like you and press like yours are obstacles to India’s development in all aspects. You pull it back, ok? But you know what? You try pulling it cause you’re already down.

I was shocked by glancing at a headline, how dare to write such a line. Who the hell u guys to decide weather India is ready to receive companies or not

India is a democracy and people are allowed to express their views. Plus criticism is important to make improvements and progress, without criticism you don’t go anywhere.

Only a moron will invest in two penny thrid class poor Socialist backward corrupt Bharat

Than why are you living here go from our lovely Bharat.