In comparison to the Western Ghats, which have witnessed the movement of traders and monks as early as the first century CE, the Eastern Ghats rarely feature in our imagination of the past. But their peoples have played a crucial role in the history of South India, especially in the fertile plains of Andhra Pradesh. They were courted by the 16th-century emperors of Vijayanagara and were remarked upon by Mughal courtiers. Just last week, a Mughal painting depicting a Chenchu couple from the Eastern Ghats was sold by Christie’s for an eye-watering £693,000.

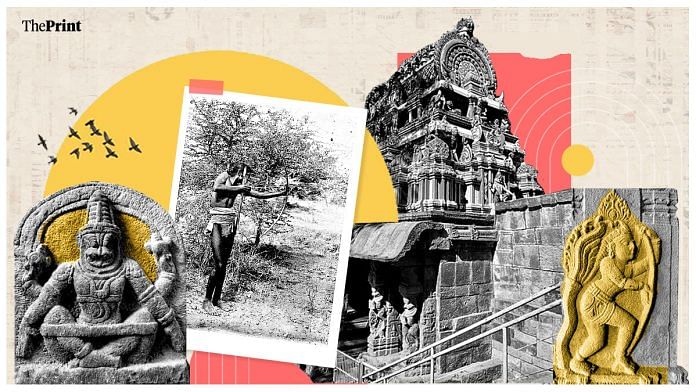

But the significance of the Eastern Ghats goes beyond this. From the Alvars of the Tamil Vaishnavite tradition to the temple-patron warlords of 12th century Andhra Pradesh, the peoples of the Eastern Ghats have also contributed to the evolution of Hinduism as we know it. This is especially evident in two temples that draw hundreds of thousands of pilgrims annually: Draksharamam in the Godavari delta and Ahobilam in the Eastern Ghats.

From cowherds to kings

On the bank of the Godavari River, which pours from the Deccan into the Andhra Pradesh coast, stands the Shaivite temple of Draksharamam. While unassuming today, this site held extraordinary significance during the medieval period, especially from the 10th to the 15th centuries CE. Like the Amaralingeswara temple at Amaravati, its linga may have been repurposed from a Buddhist stupa. In the 11th century, it sat on the war-torn frontier between the Chalukya empire of the Deccan and the Chola empire of the deep South, drawing their patronage. Royals from Odisha and officials from Sri Lanka also frequented the temple, advertising their devotion and proximity to its deity.

But what I want to explore here is just one strand of its history: its enduring connections with the Boyas, a warlike people who were originally hunter-gatherers, active across the Deccan and Tamil Nadu. In their paper titled ‘Kings, Temples and Legitimation of Autochthonous Communities: A Case Study of a South Indian Temple’, historians PS Kanaka Durga and YA Sudhakar Reddy studied 390 inscriptions on the temple walls. Spanning four hundred years, these inscriptions reveal the social history of the Boyas: from their unassuming arrival on the coast to their emergence as warlords and royal officials.

Originally from the Nallamala ranges of the Eastern Ghats, the Boyas appear to have migrated to the coast in search of opportunities amid the endless warfare of medieval Andhra politics. The region finally stabilised in the late 11th century when a prince of Andhra descent took the Chola throne as Kulottunga I. Thereafter, various local lords, working as Chola officials, tried to recruit Boya manpower for themselves. Durga and Reddy discovered that 882 Boyas were named in the temple’s inscriptions from 1039 to 1453, initially serving as custodians of the temple’s cattle (which numbered 13,440 over this period). Within a century—as Chola power faded in the region—Boyas at Draksharamam were identified as military personnel, bodyguards, and village owners. By the 13th century, they were mentioned as royal ministers and officials, undertaking public works and making donations to the temple. Of course they would: from the perspective of medieval Boyas, their ties to the deity at Draksharamam had quite literally rewarded them with increasing wealth and status in the world.

Of course, other castes disputed this status, viewing the Boyas as upstarts. Many Boya priests claimed to be Brahmin. In Edgar Thurston’s Castes and Tribes of South India—a colonial-era ethnographic project that involved extensive field research—the Boyas were recorded as claiming descent from a Brahmin bandit, who later became the sage Valmiki. In other legends, as noted by Durga and Reddy, they were said to be descended from Nishada: a horrid figure banished to the forests in the Mahabharata. While agrarian society needed the Boyas and used them as mercenaries and officials, it never granted them exalted kshatriya status.

Also read: Odisha’s medieval queens weren’t ‘ideal wives’–they fought off invaders, ordered war & murder

Narasimha’s in-laws

The medieval caste system was heterarchical—it had many competing players, all with shifting status with regard to each other. The Boyas were considered of higher status than another hunter-gatherer group that remained in the Eastern Ghats: the Chenchus. The Boyas claimed to be the only legitimate descendants of Nishada, thereby securing a place (even if a lowly one) in the grand mythos of the Mahabharata. However, as recorded by Thurston, they argued that the Chenchus were Nishada’s illegitimate offspring, thus ensuring that the Boyas’ status was marginally higher.

The Chenchus had their own claim to fame. Across the hilltops of the Eastern Ghats, they worshipped gods in the form of pillars, variously appropriated by Buddhists, Shaivites, and Vaishnavites. They shared this practice with the hill-peoples of present-day Odisha, one of whose pillar-deities, Stambheshvari, was featured in an earlier edition of Thinking Medieval. Pillars also became integral to the myths of Narasimha around this time: he is depicted emerging from a pillar to rescue his devotee, Prahlada, from his demonic father. In her paper ‘Evolution of the Narasimha Legend and its Possible Sources’, historian Suvira Jaiswal argued that the pillar in these myths was an idea assimilated from the hill-peoples.

One major Chenchu site was Simhachalam. Initially under Shaivite control, it became a stronghold of Vaishnavites by the 11th century, with claims that the divine man-lion Narasimha had manifested himself in the Shiva linga. According to Jaiswal, this linga was originally a sacred pillar-god of the hill-peoples. But perhaps the most important hill-temple during this period was the one dedicated to Narasimha at Ahobilam, as studied by Professor Aloka Parasher Sen in her book Gender, Religion and Local History: The Early Deccan. From the 15th century onwards, sculptures were commissioned at Ahobilam, depicting a local legend: a beautiful Chenchu woman named Chenchita was believed to have charmed Narasimha. The god—depending on the source—either immediately took her to Ahobilam or courted her and paid the surrounding bamboo forests to the Chenchus as a bride-price. Although she was called Chenchu Lakshmi, the goddess was not Narasimha’s primary consort at the temple; that status was reserved for Lakshmi herself.

The different versions of this story, according to Prof Sen, reveal ambiguities in how the Chenchus perceived themselves in relation to Ahobilam. On one hand, Chenchu legends (as recorded by Thurston) claimed that the goddess Chenchita, unhappy with being taken away, ordained that Chenchu girls would no longer be as charming as her, ensuring their protection from covetous eyes, including those of “Nawabs” and “Sahibs”. Emperor Krishna Raya of Vijayanagara, who appeared in a previous edition of Thinking Medieval, also made offerings at Ahobilam in the 16th century. He wrote, with annoyance, of his dealings with hill-peoples. “Trying to clean up the forest folk is like trying to wash a mud wall,” he grumbled. “There’s no end to it. No point in getting angry. Make promises that you can keep and win them over. They’ll be useful for invasions, or plundering an enemy land. It’s irrational for a ruler to punish a thousand when a hundred are at fault.” Evidently, at least some hill-peoples raided Vijayanagara territories or otherwise created trouble. Nevertheless, gifts from ‘upper-caste’ royals had a lasting impact.

As the Ahobilam complex expanded, some Chenchus proudly claimed descent from Narasimha, while others regarded him as their in-laws. Many Chenchus today participate in Ahobilam’s rituals and bear the Vaishnavite mark on their foreheads. The legend of Chenchita even extended beyond the Eastern Ghats. The god Shiva at Srisailam is also believed to have married a Chenchu woman. To my surprise, I encountered this legend depicted in a carving at the Someshvara temple in Ulsoor, near my former workplace in Bengaluru. In a 17th or 18th century carving, the god, in the guise of a hunter, is depicted helping Chenchita remove a thorn from her foot. He is then shown proudly fetching two deer, as a bride-price to marry her. Hundreds of years of conflict and accommodation, interactions between the ancient peoples of forest, hill, and field, distilled into the charming stone faces of a god and goddess.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of Lords of the Deccan, a new history of medieval South India, and hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti. Views are personal.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval‘ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

(Edited by Prashant)