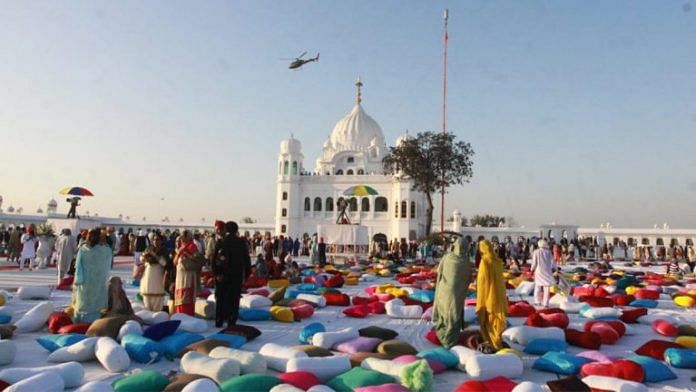

Is peace in danger of breaking out between India and Pakistan? The 4.7-km-long Kartarpur Sahib corridor that connects Dera Baba Nanak in Punjab with the holy Sikh shrine in Narowal district of Pakistan Punjab, where Guru Nanak lived and died in the 16th century, is reopening today.

Union Home Minister Amit Shah tweeted to say that the reopening of the corridor, in time for Gurpurab celebrations on 19 November, reflects the “immense reverence” of the Narendra Modi government for Guru Nanak and the Sikh sangat.

Certainly, Shah is hoping that the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) will get the credit and earn its reward in the coming election in Punjab. Only on Sunday, a BJP delegation from Punjab met PM Modi and requested for the corridor to be opened, but other state leaders cutting across the political spectrum have not been left far behind.

Akali Dal MP Harsimrat Kaur Badal, who visited Kartarpur Sahib in Pakistan in 2018, as the Modi government’s representative – her party, the Akali Dal, was part of the BJP-led alliance at the time – for an informal inauguration, had recently written to the PM on this exact account, while Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC) president Bibi Jagir Kaur and Congress leader Navjot Singh Sidhu have made similar requests.

Significantly, Pakistan had said a fortnight ago it was ready to accept Sikh pilgrims to Kartarpur Sahib and requested India to open the corridor on its side that had been shut down when Covid hit last March.

So, is Pakistan signaling a peace overture with the move? Remember that only a week ago, Pakistan Prime Minister Imran Khan had agreed that wheat consignments for Afghanistan would be allowed overland through Pakistani territory. That gesture, too, could not have happened without the powerful Pakistan military establishment being on board.

And so, the big question: Is the Pakistan military signaling that it is ready for a step-by-step overhaul of the relationship with India?

Of course, the jury is out on that question. First of all, even if the military is indeed making such an overture, what is its motive? Some astute political observers say the Pakistanis are overstretched on the Afghanistan front and they badly need some let up.

Also read: India wants to be a big player in Afghanistan, so why isn’t it giving visas to Afghans?

India’s interest

But why are Indian political folks making such a big show of interest? Certainly, every political party would like to cash in on the genuine religious ardour associated with the Sikh gurus. But when the religious dust settles and the political chaos associated with the exit of Amarinder Singh from the Congress party resurfaces, every politician worth their salt will look at how the other stacks up.

Certainly, in Punjab, the Congress is substantially weakened, the BJP isn’t strong enough, the state’s Jat Sikh community isn’t about to forgive the Akali Dal in a hurry, and the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) is hardly able to channel the confusion into a cohesive alternate narrative.

Every political party also knows that the BJP has an advantage on this count because it is in power at the Centre; moreover, a breakthrough is possible only if the Pakistan military establishment, which runs the country and manages all its foreign policy decisions related to India, is on board.

It is more than likely that Congress leader Navjot Singh Sidhu fancies he has a chance to firm up his own political stock. He had travelled to Pakistan on the eve of the Kartarpur Sahib corridor’s inauguration by Pakistan PM Imran Khan in November 2018 – a trip that resulted in a bear hug with Pakistan Army chief Gen Qamar Javed Bajwa. And since Bajwa remains the real power behind the Pakistani throne, the Congress leader may believe he is higher in his pecking order of affection than other Indian leaders.

Back, then, to the Pakistan military establishment, whether it is sending India a message despite the bad blood of the recent years and why.

Also read: India’s distance with Pakistan and Bangladesh growing. Cricket can help

A military vs Imran Khan show

It is no longer a secret in Pakistan that Imran Khan, a protégé of the military establishment, is running afoul of his mentors, those who put him on the prime minister’s chair in 2018. The recent brouhaha over changing the ISI chief, from Faiz Hameed to Nadeem Anjum, when Imran Khan held onto the formal announcement of the new man, was an indication of fraying trust.

There are three reasons why Imran Khan may no longer be the military’s charmed favourite he once was in 2018. The first is the deep crisis in the Pakistan economy. According to the World Bank, Pakistan is on the list of top ten economies with the largest foreign debt. Its gross external financing requirement is $23.6 billion for the current year and another $28 billion for the coming year. In June, as Covid swept the region, the economy contracted for the first time in 68 years.

Second, while Pakistan’s assiduous cultivation of the Taliban has ensured it primacy of place in Kabul and the regime’s interior minister Sirajuddin Haqqani has brokered a deal between the Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) terror group and the Pakistan government, the fact remains that Afghanistan is in the middle of its own economic catastrophe and Pakistan is unable to help it.

Third, the political scene in Pakistan is heating up, even though elections are not due until 2023. Former chief of Supreme Appellate Court Gilgit-Baltistan, Rana Shamim, has said in an affidavit that he was witness to Pakistan’s former chief justice Saqib Nisar telling a high court judge that the latter must on no account release then-prime minister and PML(N) leader Nawaz Sharif and his daughter Maryam Nawaz from jail on the eve of the 2018 elections.

Nisar has since rubbished the accusations, but Shamim is said to be holding firm. Remember that the Pakistan military contrived to not just oust Nawaz Sharif but got him sentenced to 10 years in jail in 2018, based on allegations in the Panama Papers that Sharif had bought property in London from allegedly ill-gotten wealth; that Sharif, subsequently, was allowed to go into exile in London, from where he has since launched a series of scathing attacks against the military.

The big question now is, if the Pakistan military is upset with Imran Khan, what are its alternatives? It isn’t about to let go of the sheer, untrammeled power with which it has ruled Pakistan for most of its existence. Can the military swallow – no, allow – an untamed Nawaz Sharif to rule Pakistan? If not, then who?

For the moment, the dust in both sides of the Punjab is refusing to settle. In India, the elections in February will throw up the state’s representatives, but in Pakistan it could be a longer haul.

One thing is clear. When the people decide, then elected leaders as well as the unelected military must fall in line. Peace may not be breaking out in the subcontinent yet, but the road to that goal is increasingly less fuzzy.

Jyoti Malhotra is a senior consulting editor at ThePrint. She tweets @jomalhotra. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant)