From Tamil Nadu to West Bengal to Assam, political competition is heating up as parties do their electoral math. While in Tamil Nadu, it’s the BJP-AIADMK coalition that will take on the Congress-DMK combine, West Bengal is witnessing a triangular contest between the TMC, the BJP and the Congress-Left Front-Indian Secular Front. Assam, too, is likely to see a three-cornered fight between the BJP-led front that has the support of the AGP, the Congress-led Grand Alliance that includes the Left front, the AIUDF and AGM, and a bunch of regional players. But will this hyper political competition benefit the voters when governments are formed in these states?

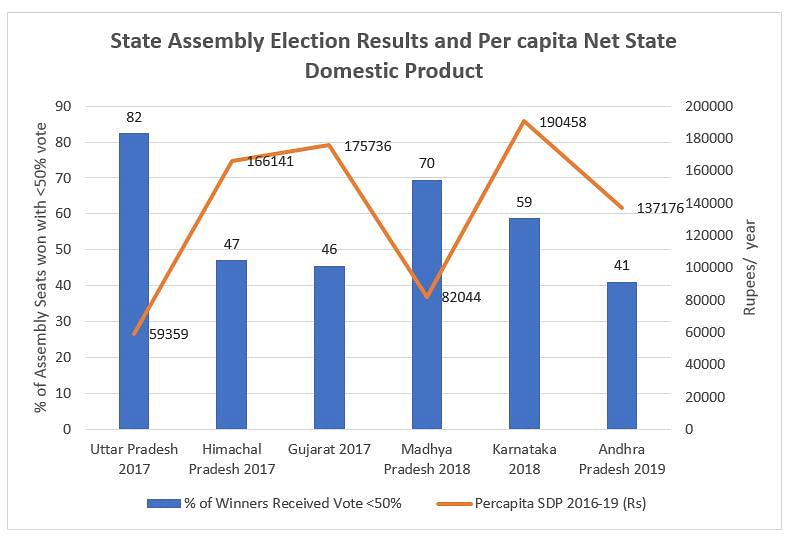

To investigate the association between political competition and development, I looked into election results and economic indicators of few states. I have considered the percentage of winners in state assembly elections obtaining votes less than 50 per cent as an indicator of political competition. Assembly polls in a few states during the last five years have been considered – Uttar Pradesh (2017), Himachal Pradesh (2017), Gujarat (2017), Madhya Pradesh (2018), Karnataka (2018) and Andhra Pradesh (2019). As an indicator of development, I have considered the average per capita state domestic product (SDP) between 2016 and 2019.

The higher the percentage of votes obtained by the winners in an election, the lower is the political competition. Hence, a higher percentage of winners obtaining less than 50 per cent votes in a state assembly election is an indicator of higher political competition. I observe an inverse relation between the percentage of winners obtaining less than 50 per cent votes and per capita SDP during the election years. This implies that political competition and development are negatively related.

In 2017 Uttar Pradesh assembly election, 82 per cent winning candidates got less than 50 per cent votes. Among the states under consideration, UP also registered the lowest per capita SDP at Rs 59,359 during 2016-19. Madhya Pradesh, which has the second lowest SDP at Rs 82,044 during 2016-19, saw 70 per cent candidates who won the 2018 assembly election get less than 50 per cent votes. On the contrary, only 46 per cent candidates won the election with less than 50 per cent vote in 2017 Gujarat assembly election. The state has per capita SDP at Rs 1,75,736 during 2016-19, second highest after Karnataka at Rs 1,90,458. In Karnataka, 59 per cent winners in the 2018 assembly election received mandate of less than half of the total voters. In Himachal Pradesh, only 47 per cent of such winners occupy assembly seats while the per capita SDP is as high as Rs 1,66,141. (Handbook of Statistics on Indian Economy, Reserve Bank of India, 2020)

Also read: ECI directs petrol pumps to remove hoardings featuring PM Modi’s image within 72 hours

Political competition doesn’t guarantee positive impact

The nature of electoral competition and per capita state domestic product are fairly stable in a state in the short run. It is difficult to tell if political competition impacts development or vice versa, but the association between them is evident. They may also feed each other. My study, conducted with my colleague Tirthankar Nag, on basic service provision in slums of Kolkata, published in Development Policy Review in 2016, reveals that political competition need not necessarily have a positive impact. The percentage of votes obtained in municipal elections has a positive impact on quantity and quality of water supply services but has a negative impact on drainage services in the slums. Hence, low competition or higher political domination by the winner is better for water supply.

To understand and get a probable explanation of the negative co-relation between political competition and development, the concept of political clientelism should be first understood. Political clientelism is a system of exchange where political subordination is traded with discretionary granting of public resources and services. In this system, the political patrons privatise the public goods and offer it to their clients, a group of people who extend their allegiance to their political patrons in return. Political clientelism is one of the mechanisms to ensure political support. This is all the more necessary in the backdrop where high political competition and political fragmentation is coupled with lack of credibility of contestants to deliver broader public good, which would benefit the population in the long run. By committing specific public good or service to specific group(s), politicians become reliable enough to attract support and vote. The fallout of political clientelism is lesser provision of broader public goods such as education, health and employment for masses.

In their article published in 2004 in Economic and Political Weekly, Philip Keefer and Stuti Khemani argue that political clientelism is one of the major reasons why the majority remain poor in a democratic nation. The broader public good, such as quality health and education, eludes the population perpetually. This does not mean that resources are not spent on the poor or goods and services catering for the poor are not delivered. Monetary resources are spent on subsidies and direct transfers, where political returns are more direct and certain. The existing ethnic polarisation in the society, dominated by religion and caste, can only make it easier to establish and maintain clientele. Political representatives from the same ethnic group may appear to be the most reliable one. However, the expenditure made or goods and services delivered may not have long-term implications on development of the same group.

Also read: BJP, AGP wrangling over seat-sharing for Assam polls, senior leaders to meet Amit Shah, Nadda

Political clientelism and political competition

Our study on political clientelism, based on basic service provision in slums of Kolkata, reveals that services managed by lower level of a municipal authority, like water distribution and drainage services, are affected by clientelism. However, capture by politically influential and dominant social and religious groups is likely to take place for important services like water supply. Higher political clout of winners who have obtained a higher percentage of votes is associated with sufficient water distribution. But, if a region has higher political competition along with political fragmentation, then political clientelism is bred leading to lesser households receiving sufficient quantity of water supply.

Inaugurating of projects, launching schemes or increasing subsidies before an election are acts of political clientelism. These sops may help a certain group of poor but their implications may get diluted in the long run and in a broader context. The most dreadful form of political clientelism is distribution of cash and liquor. A more common form of political clientelism is building schools without delivery of quality education.

In a vibrant democracy, there should be many politicians willing to offer benefits and meet people’s demand. Thus, political competition should ideally be an index of democracy impacting development positively. On the contrary, evidence suggests that political competition is associated with underdevelopment. Instead of being an index of democracy, it may be treated as an index of political clientelism that leads to the overall underprovisioning of broader public goods and services. In this context, it is important to ponder over an alternative democratic mechanism that would meet people’s long-term development needs.

Indranil De @IndranilIndia is Associate Professor, Institute of Rural Management, Anand. Views are personal.

Per capita SDP is a better indicator of development than growth rate. High growth may not represent high development. A region is more development when per capita availability of income is higher. However, development is a broader concept, not only restricted to per capita income or SDP. in that sense, it per capita SDP is only one of the indicators of development.

I am no statistician nor an economist, but I wonder whether it would not be more wise to study the growth in per capita SDP, rather than the current per capita SDP itself in such a study?