As a military historian, filmmaker and author Shiv Kunal Verma, the son of an army general, has a distinct edge. His other advantages in writing 1965: A Western Sunrise are his own past experiences, from having filmed the Kargil War to extensively operating with the Indian Army, the Indian Air Force and the Indian Navy in virtually all theatres. He not only has excellent sources but also the ability to separate the chaff from the wheat when it comes to looking into the fog of war and getting to what may have happened.

Based on detailed research of the terrain and numerous interviews with soldiers, bureaucrats and others who had a first-hand view of the conflict, 1965: A Western Sunrise is a lucid, definitive account of the second major conflict between India and Pakistan. As was the case with Shiv Kunal’s previous book, 1962: The War That Wasn’t, he has managed to knit together the political and the military aspects of this extremely complicated war that was fought on various fronts. A Pakistani military historian, while commenting on this book, said, “The writer gives very interesting background details to each relevant person or subject.”

Pakistan’s delusion

Shiv Kunal starts the book by highlighting the politico-military transformation that took place in India, and in Pakistan, in the aftermath of the 1962 India-China war. In March 1963, Pakistan, under General Ayub Khan, signed the Boundary Agreement with China, ceding to it the Shaksgam Valley in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir (PoK). Post SEATO and CENTO Agreements, the Pakistan Army had received new weapons and equipment from the US and thus acquired an edge over India in armour, artillery and air-power. In addition, its economy was doing extremely well. Along with all this, the Indian Army’s collapse in the 1962 conflict with China had induced a sense of bravado and delusion in the Pakistan Army; that it could replicate what the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) had done.

According to Shiv Kunal, Pakistan’s Foreign Minister Z.A. Bhutto was not only encouraged but also got the idea to annex Kashmir through a force of arms from Mao Zedong. Unfortunately, Pakistan did not take into account the rapid changes that had taken place in the Indian Army post 1962, both in new raisings and hard training. Pakistan has often made wrong assumptions and indulged in self-deception vis-à-vis its bigger neighbour. It would do much the same during the Kargil War in 1999.

In April 1965, Pakistan Army took the initiative in the Rann of Kutch with intermittent skirmishes to test out its new doctrine, and the Indian capacity to react. This was then immediately self-declared as a ‘huge Pakistani victory’ where the buzdil Indians were cannon fodder for Pakistani soldiers. Four months later, Op Gibraltar was launched with about 12,000 Pakistani soldiers (the author differs with many others who assessed the number of infiltrators to be near 30,000) crossing the Line of Control in Kashmir dressed as locals (a similar ruse was used in the Kargil War). The author calls them “wolves in sheep’s clothing”. Finding no sympathy among Kashmiris, the infiltrators were decimated by the Indian Army, which also captured the Haji Pir Pass and some Kishenganga bulges that were inside the PoK. This also cut off the escape routes for most of the infiltrating columns that had entered the Valley, which is never a very happy situation for anybody.

With the various infiltrating forces in disarray, to cover for the failure of Op Gibraltar, Pakistan launched Op Grand Slam on 1 September 1965, which was aimed at over-running Chhamb-Jaurian and cutting off the road from Akhnoor to Rajouri and Poonch. This activated the air forces on both sides. India retaliated with the push forward across the International Boundary in the Lahore and Sialkot Sectors. Hard and memorable battles were fought thereafter at Dograi, Barki, Khem Karan, Chawinda, and some in the Rajasthan Sector. The author has covered each of these battles in great detail. In these narrations, a few more maps would have been helpful to understand the described manoeuvres.

Also read: How the Indian army went deep into enemy territory to take the Haji Pir pass in 1965 war

Military failure a common factor

Besides covering details of the battles fought by the Army, Navy and the Air Force, Kunal has also delved into many questions that are often raised regarding political and military strategy, political and military leadership, and who won and who lost the war. His understanding of the larger geo-political scenario also allows him to often join the dots and arrive at some extremely interesting conclusions.

It is well known that the political leadership and bureaucracy in India takes little interest in defence policies or the equipping and modernisation of the armed forces during peacetime. But when the nation goes to war, they seldom interfere in the military’s operational planning. Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri had taken charge barely a year before the war was thrust on India. There was absolutely no interference on his part in the military operational planning. The political leadership thus cannot be blamed for anything except in giving up the Haji Pir Pass during the final negotiations at Tashkent. Haji Pir, a major infiltration route of militants from PoK, continues to rankle the Indian Army. The author suggests that this political decision was taken after consulting with then-Army Chief, General Jayanto Nath Choudhury.

Shiv Kunal, in his narration, is highly critical of the military leadership for poor planning and operational conduct during the war, with most of the blame going to Choudhury, considered “an impetuous and unthinking Army Chief”. The disdain Chaudhuri had for the other two Services was clear in his handling of affairs. Air Marshal P.C. Lal, who would become the Chief of Air Staff (CAS) six years later, said that Chaudhuri treated the whole business of fighting Pakistan or China as “his personal affair, or at any rate that of the Army’s alone, with the Air Force a passive spectator and the Navy out of it altogether”. Chaudhuri had much the same attitude when it came to dealing with his own headquarters. For him, ground-level planning and logistics seemed to have little meaning.

Other generals too have not escaped the author’s wrath. “Indian generals, in the actual conduct of operations, repeatedly bungled, often resorting to tactics that bordered on the bizarre.” In an interview to India Legal, Kunal said, “The Indian (Army) not even getting to the Ichhogil Canal, except for Dograi and Barki in the Bari Doab, and failing to get past Chawinda in the Rachna Doab tells its own story.” The Western Army Commander, Lt Gen Harbaksh Singh, had his moments ignoring Chaudhuri’s orders, saving a disaster in the Majha Belt of Punjab, but the entire top brass, according to the author, was a miserable failure. Indeed, there were a large number of sackings following higher command lapses. “The few heroes that did emerge were the commanding officers and some of the younger officers,” he writes.

Kunal also says “there was complete lack of cohesion between the IAF and the Army which bordered on the criminal”. The higher command failed to harness the operational potential of maximum strategic effect. This handicap, unfortunately, continues to haunt the Indian military even today due to much delayed political action to create an integrated defence staff under the Chief of Defence Staff (CDS).

Ironically, the situation on the Pakistan side was no different. Their military commentators and historians believe that poor military leadership at the higher level stands out as the principal cause of failure of the Pakistan Army to inflict a decisive military defeat on India, and that General Ayub Khan was directly responsible for the leadership failure of the Pakistan Army. The fact is that in all the major offensives of the 1965 War – be it Chhamb, Lahore, Khemkaran, Asal Uttar, Chawinda – both the Indian and Pakistani armies were total failures.

However, another fact, acknowledged by both sides, is that all along the Indo-Pakistan International Border, large numbers of and large-sized villages, multiple water obstacles, limited fields of fire, and boggy terrain had massively increased the power of defence. This situation is much worse today.

Also read: The truth of Galwan must come out, unlike the 1965 battle with Pakistan in Khemkaran

So, who won the war?

Wars are won or lost depending upon the success or failure to achieve the political aim/objective. Pakistan failed to annex Kashmir, which was its primary objective. In the military domain, according to the official website of the Indian Army, Pakistan suffered heavily in men and material, in spite of her superiority in arms and equipment. This conflict began with the Rann of Kutch and culminated with the subsequent ceasefire violations that continued until February 1966.

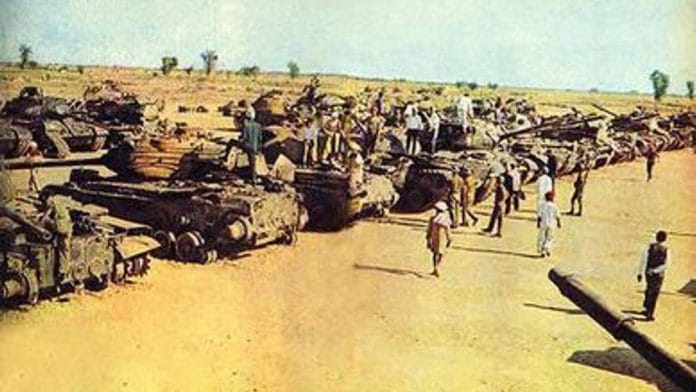

It is estimated that the Pakistan Army lost 5,800 soldiers; many more were wounded. India lost 2,763 men; 8,444 wounded; and 1,507 missing. Indian tank losses were 80 as against 475 of Pakistan. Considering Pakistan Army’s numerical advantage in tanks, artillery and other weapons and better equipment, the consensus is that India came out on top. The PAF, on the other hand, statistically had out-performed the IAF, but then just when the Indians were coming into their own, General Chaudhuri threw in the towel. The biggest tragedy — and India’s biggest failure in that war — was that it did not completely destroy Pakistan’s war-making capability when they were on the mat.

Devin T. Hagerty, in his book South Asia in World Politics, wrote, “By the time United Nations intervened on September 22, Pakistan had suffered a clear defeat.” Arif Jamal wrote in Shadow War, “This time, India’s victory was nearly total: India accepted cease-fire only after it had occupied 740 square miles though Pakistan had made marginal gains of 210 square miles of territory.” In Pakistan, most people, schooled in the belief of their own martial prowess, refused to accept the possibility of their country’s military defeat by “Hindu India”. They put the blame for their failure to attain military aims on the ineptitude of Ayub Khan and his government.

Though most journalists and researchers have stated that India won the war, there are some who have felt that the war was militarily inconclusive or ended in a draw. In this book, Shiv Kunal writes, “Instead of victory, the war ended in a stalemate that enabled both sides to claim victory.”

The intensity and scale on which the 1965 War was fought numbs the mind even today. Shiv Kunal Verma’s ruthless holding of a mirror to the leadership, which some might say is a bit opinionated, his immense research, his very detailed descriptions of each action with the background of the higher political and military leadership juxtaposed, makes 1965: A Western Sunrise a very interesting and readable book. Beyond a shadow of doubt it is a commendable contribution to India’s military history narratives.

General V.P. Malik (Retd) is former Chief of the Army Staff. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant)