Insurgency has been part of India’s politics since the Naga revolt of the 1950s. Yet, many aspects of these conflicts have been shrouded in secrecy or ambiguity. In a recent study published in the academic journal India Review, we used open-source data to explore fatalities and demography in India’s internal security forces. While there are interesting patterns in security force fatalities, perhaps the most illuminating findings come in unpacking the regional composition of India’s key central security forces. Who fights and dies in India’s internal wars? Which states send their people to the security forces and how important are they politically?

Although there are important caveats to our data and analysis, we see consistent regional imbalances in the composition of the Indian Army, the Border Security Force (BSF), and the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF). Some states appear to be dramatically over-represented, while others consistently staff forces below their share of India’s population. These patterns are in part the result of intentional strategies of recruitment, while economic conditions and historical networks and traditions of service also likely contribute.

Source of data

Where does the data come from? We first collated information from BSF and CRPF commemorative booklets honouring these organisations’ ‘martyrs’ killed in action in counterinsurgency operations or other domestic security missions (for example, cross-border smuggling interdictions). These documents describe in great detail individual incidents involving security force fatalities. Take, for instance, one fatality in Manipur in August 1994:

“On the 13th of August 1994, CRPF troops of 127 Bn launched an operation against insurgents at village Maidanpur*, Manipur. As the troops were nearing to their target, the insurgents waiting in an ambush opened indiscriminate fire at them. The troops immediately got down from the vehicles and launched a counter-attack. During fierce encounter, Shaheed Nk/ Dvr Abdul Quadir received severe injuries and sacrificed his life for the nation. The martyr laid down his life for the honour and integrity attached to a Uniformed Trooper.”

These are impressively detailed commemorative efforts that provide insights into where and when the BSF and the CRPF suffered fatalities. The Bharat Ke Veer initiative by the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) now provides data on more recent fatalities involving personnel of the seven Central Armed Police Forces (CAPF). Similar, though much less organised and more scattered, data also exists for state police forces: there are state-level pages (for instance, Jharkhand) and an MHA site that tries to aggregate state data with the ministry’s information. There is huge variation in the existence and quality of state police pages, while the MHA aggregation site is extremely difficult to use and appears incomplete. We therefore focus on the richer and more systematic CRPF and BSF information.

Also read: CAPFs won’t upgrade their Recruitment Rules for pay parity with IPS officers

Limitations involved

Beyond patterns of fatalities, the CRPF and the BSF memorial documents importantly provide the service member’s home village and state. These allow us to very roughly measure the overall distribution of regional recruitment over these forces’ history. We compare the proportion of fatalities from a state to the proportion of the state’s population in the 2011 census.

There are crucial limits to our analysis: there are different recruitable populations across states that are not identical to the overall state population (i.e. some states have a larger share of young men than others), these age distributions have changed over time, we are limited in our knowledge of how recruitment strategies have shifted over time, we could not find Assam Rifles casualty information, and the data end in 2015. The smaller proportion of young men in more developed western and southern Indian states, for instance, may make under-representation appear more pronounced than it actually is. We also assume that patterns of fatalities in the MHA-controlled forces broadly mirror patterns of recruitment. The findings should therefore be taken as suggestive, laying the basis for future work.

Disproportionate representation

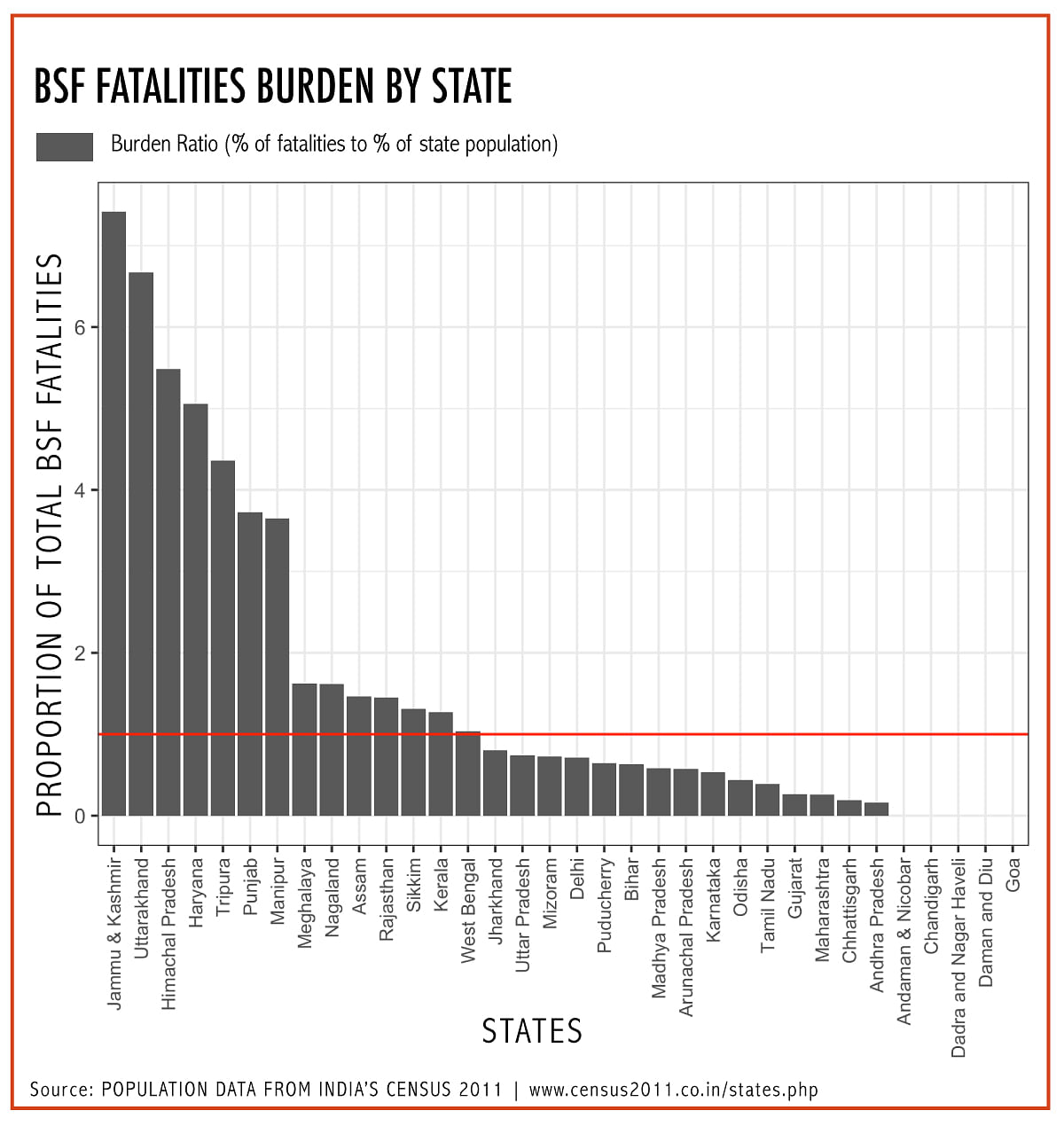

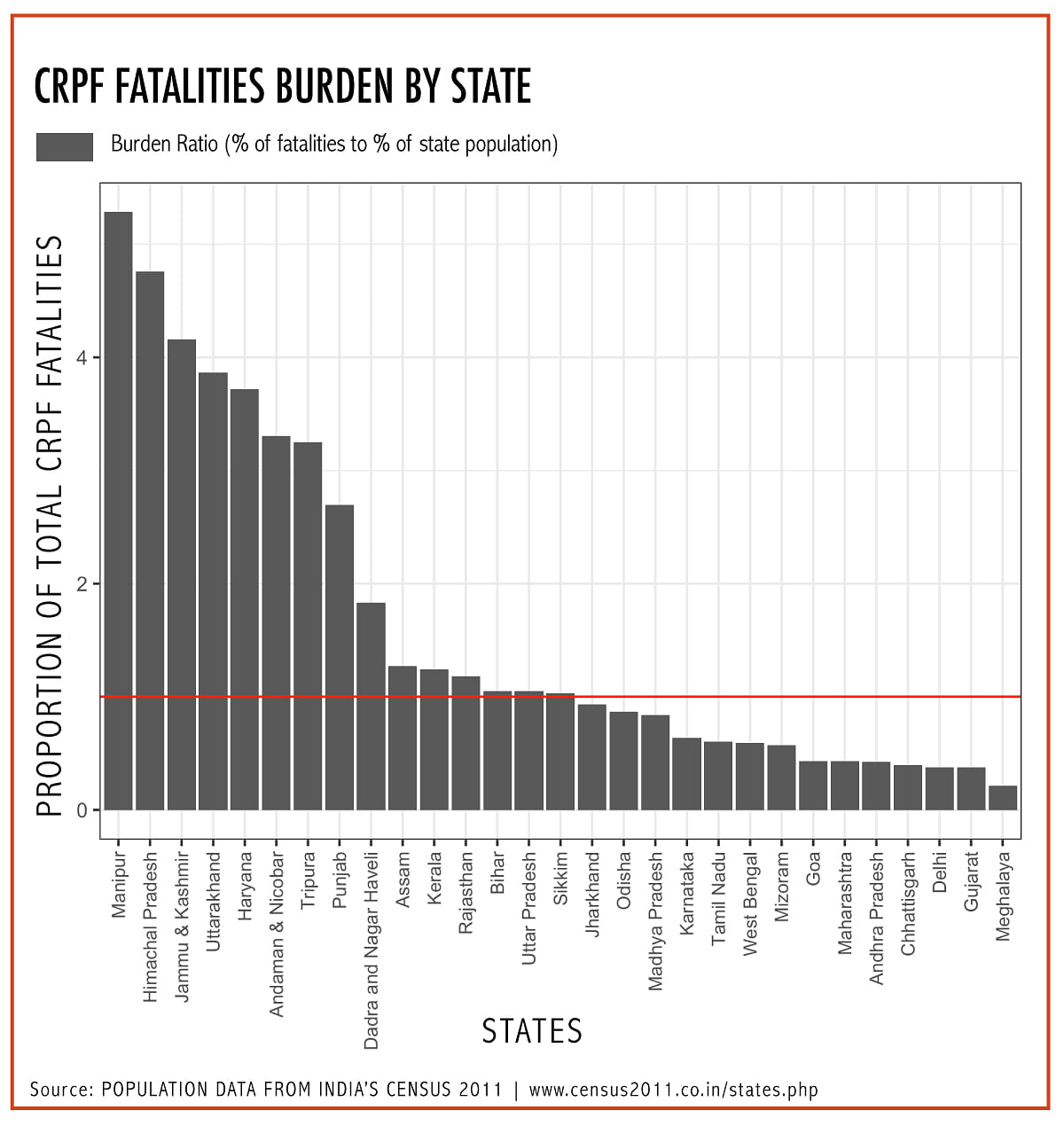

With these important caveats in mind, we found recurrent disproportionality in the regional composition of the BSF and the CRPF. We know from a 2015 MHA answer in the Lok Sabha that the BSF and the CRPF intentionally aim to over-represent border and/or conflict states. These patterns are borne out in the data.

In the BSF data, we see border states disproportionately represented. Jammu and Kashmir, Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, Haryana, Tripura, Punjab, and Manipur are most striking in their over-representation. Non-border states like Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh are, unsurprisingly, under-represented in this population, as well as some border states like Gujarat and Bihar.

The CRPF similarly shows over-representation of areas that have experienced conflict. Manipur, Jammu and Kashmir, Tripura, Punjab, and Assam are among the states which are overrepresented in CRPF fatalities, relative to these states’ proportion of India’s overall population. This makes sense given their conflict histories: CRPF policy of over-representing areas of insurgency would lead to a tendency toward inflating their states’ share of the force. Yet Haryana, Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Himachal Pradesh are also over-represented in CRPF fatalities despite not being similarly ‘militancy affected areas.’ Under-represented states include Chhattisgarh and Andhra Pradesh, despite being affected by the Naxalite conflict. This disproportionality in recruitment from states like Punjab, Haryana, and Uttarakhand may be due to historical networks of recruitment in traditional ‘martial’ states.

One immediate takeaway is that there is a set of states – which tend to be quite small – that are consistently over-represented in the two major MHA-controlled forces. Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Manipur, Tripura, Punjab, and Haryana all appear to punch above their demographic weight as border states and/or traditionally ‘martial’ areas.

For all the reasons identified above, we need to be careful making strong conclusions, but it may be that southern and western Indian states tend to be under-represented. There is important variation – for instance, Kerala is somewhat over-represented in both the BSF and the CRPF – but Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh, and Karnataka consistently appear on the lower end of proportionality in both forces, while the huge ‘Hindi belt’ states largely lie in between these extremes. This pattern suggests that a blend of intentional recruiting strategy, historical networks of recruitment, and economic opportunities may be driving differential demographic representation.

Also read: No takers for women’s quota in CRPF, CISF or BSF as forces strive to fulfil Modi govt plan

Locating army personnel

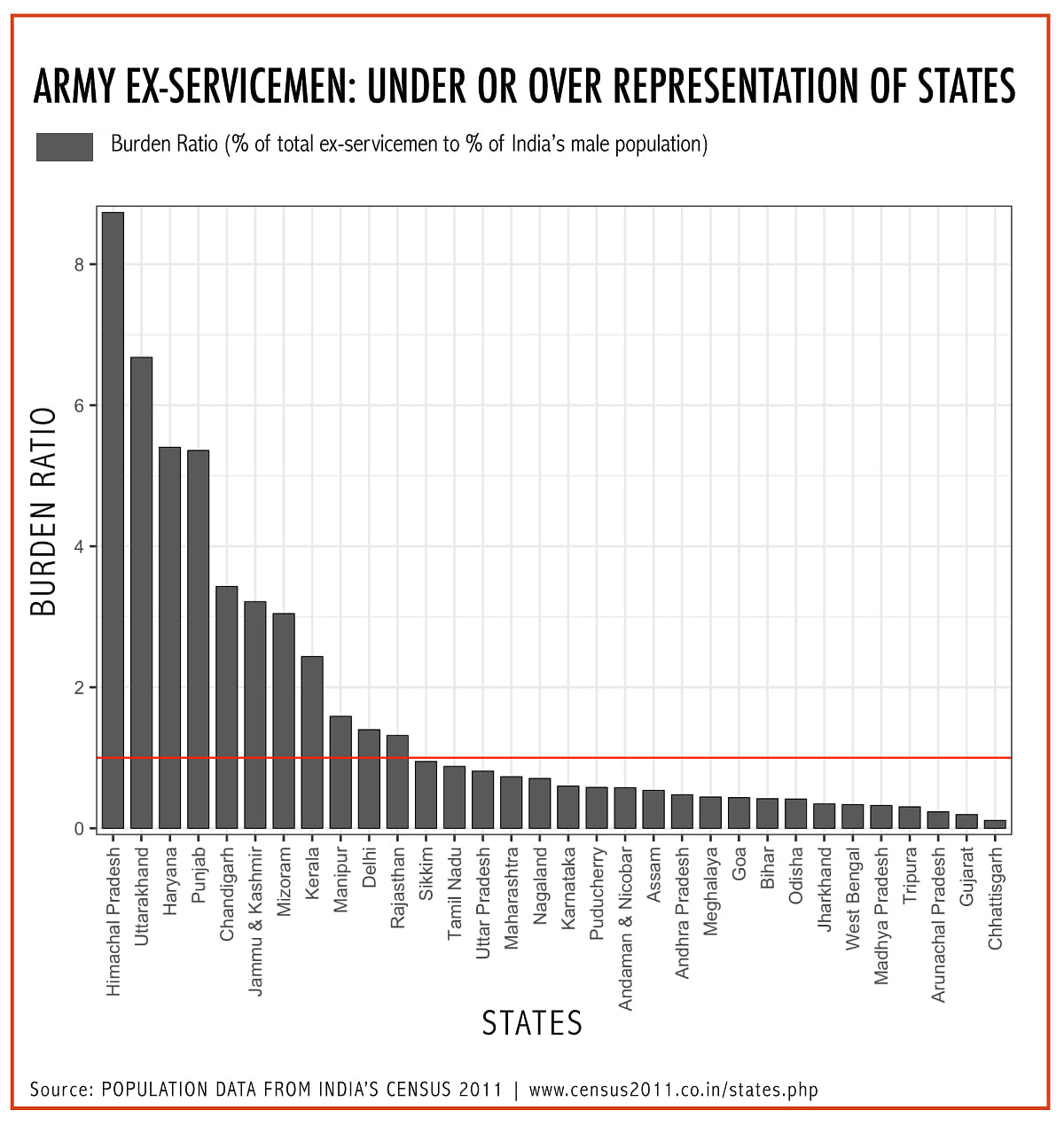

The Indian Army is deeply involved in both internal security and the defence of India’s borders. It has also been very leery of discussing its internal composition, or even providing basic public data about fatalities. Yet open source data also exists on broad patterns of regional representation. In 2017, a Ministry of Defence answer to a Lok Sabha question provided the location of ex-servicemen by state and service branch. We then identify which states are over/under-represented among Army ex-servicemen as a function of their proportion of the Indian population. As in the central armed police forces, traditional ‘martial’ regions in north India as well as border areas are over-represented: Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Haryana, Punjab, Jammu and Kashmir, Mizoram, Kerala, and Manipur all have more ex-servicemen than their share of the Indian population. This supports past findings on the composition of the Army over time.

Some ex-servicemen have retired to these areas rather than originally coming from them, and the data cannot capture changes over time, creating limits to this information. However, data on Junior Commissioned Officer (JCO) and other rank recruitment from 2011-2014 – provided in a 2014 defence ministry reply in the Lok Sabha – show a similar story. During this period, Punjab contributed roughly as many members to the Army as Maharashtra, Rajasthan as much as Bihar, Uttarakhand’s recruitment was similar to those of Tamil Nadu and Madhya Pradesh, Jammu and Kashmir contributed roughly as many as Gujarat, and Himachal Pradesh’s raw number of recruits was similar to Karnataka’s. The remarkable parity of some of India’s smaller states with some of its largest suggests that regional imbalances continue into the recent past.

There is no obvious answer to whether security forces should be regionally balanced. There may be operational reasons to draw on conflict-affected and border areas, while historical traditions of regional service can provide a source of cohesion and continuity over time. On the other hand, some smaller states like Himachal Pradesh, Jammu and Kashmir, Uttarakhand, Tripura, and Manipur – with lower number of parliamentary seats – have a much higher proportion of their population joining the service than the rest of India. This has implications for democratic accountability: those who fight and die in India’s national security apparatus are not fully representative of those who vote in its elections and serve in its government.

* The CRPF’s document, Warriors Remembered Vol 2 (1991-1997), does not appear to be correct regarding the name of the village.

Paul Staniland is Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of Chicago and is Director of the Committee on International Relations.

Drew Stommes is a PhD student in political science at Yale University. Views are personal.

This article has been updated to reflect a clarification.

Do US provide for equal representation for its 50 states and other territories? Do US women find equal representation in all military services? One way to make a military democratic and IMPOTENT is to provide for reservation amongst its services. India did that mistake in providing for representation among civil services and it ended up with a corrupt and inefficient administrative class. Nothing ever get done. Anything the government baboos touch, dies a quick death.

There are certain people from border regions, who are good at fighting and have a history of defending themselves from foreigners. Such people have an inclination to join the military. Some people are intellectually inclined. They build rockets and send satellites to moon and make delicious idlis and dosais.

Please stay within your discriminatory Yale campus and don’t try to poke your pointy-nose into something that you have no clue about. On the other hand, why don’t you write about the secret backdoor admission process of the super rich into Yale?

We should settle people from the rest of India in this state like we will do in the Kashmir valley.

Indian security forces contain mainly Rajput/Jat including (Jatts) of all states. The data also proves with Himachal, Haryana , Rajasthan& Uttarakhand being higher.