A great deal is expected from the first budget of any government. The expectations are even greater from a government that has come back to power with an improved tally. It doesn’t help that the Narendra Modi government finds itself in a challenging fiscal situation with limited options.

For budget management, 2018-19 was a difficult year. At the centre of this difficulty was a massive shortfall in tax revenue. Going by what the Controller General of Accounts has reported, the actual (provisional) net tax revenue for the Centre was about Rs 1.64 lakh crore lower than what was budgeted in 2018-19. This was mainly because the GST and income tax collections were much lower than expected.

The lower-than-budgeted GST collection could be because this was the first full year of GST, and it was difficult to find a basis to estimate the collection accurately when the target was being set. Also, a new tax system takes time to settle, and the government and taxpayers find a steady state only after an initial period of transition and turbulence. However, the income tax collection should be a cause for worry. Going by the provisional actuals, the growth in income tax collection has decelerated substantially. At about 7 per cent, the increase in income tax collection is the lowest in recent times.

Also read: Why India’s middle classes are Modi’s ‘Muslims’

Curbing expenditure

After accounting for other additional collections, this shortfall in receipts necessitated curbing expenditure to the tune of about Rs 1.3 lakh crore against the budget estimates, if the fiscal deficit was to be kept within the promised limit.

In terms of the quantum of cuts, the bulk of the spending curbs was seen in food subsidy and transfers to the states. It seems the cut in on-budget expenditure on food subsidy was met by an additional borrowing by the Food Corporation of India.

A result of the expenditure curbs was that the central government expenditure in 2018-19 was 12.2 per cent of the GDP – the lowest in more than four decades.

A bigger government is not necessarily better for the economy. What matters is the quality of governance, and not the size of the government. If a considered approach is taken to orient the government expenditure towards its core functions and improve the efficiency of expenditure, a smaller government can actually serve the economy better than a larger government. However, if the expenditure cuts are done in a haphazard manner in response to an unexpected revenue shock, the consequences can be negative.

Also read: Budget 2019 is fiscally responsible with a reforms thrust, but protectionist

Did government do it the right way

The expenditure-cutting course that the government chose for 2018-19 can also be considered in the context of the law that governs fiscal policy in India. The Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) Act now allows for an increase in fiscal deficit by up to 0.5 per cent of the GDP (about Rs 95,000 crore in 2018-19) on certain grounds.

One of these grounds is “structural reforms in the economy with unanticipated fiscal implications”. Since much of the shortfall is on account of low GST collections, the government could have partially met the expenditure by additional borrowing. This was one of those rare years when a fiscal slippage could have been tolerated while being respectful to the rule of law.

Perhaps, the government thought it was unwise to crowd out private borrowers by increasing the fiscal deficit. But does that really matter if the borrowing is anyway being done by the Food Corporation of India or other public sector entities, or in the form of bank recapitalisation bonds (earlier, bank recapitalisation was on-budget, but is now done through bonds that don’t reflect in the fiscal deficit)?

After all, the concern is regarding crowding out the private sector in the aggregate transformation of savings into investments, and not about a particular mechanism to do so. Also, moving the borrowing off-budget only postpones the on-budget expenditure. The bill must be paid at some point. Unless this functional perspective is taken into account, the economic consequences of fiscal management would have little to do with the fiscal deficit number.

Looking at the budget for 2019-20, if we compare the budgeted figures with last year’s revised estimates (as given in the budget documents), the increase in net tax revenue seems reasonable – about 11 per cent.

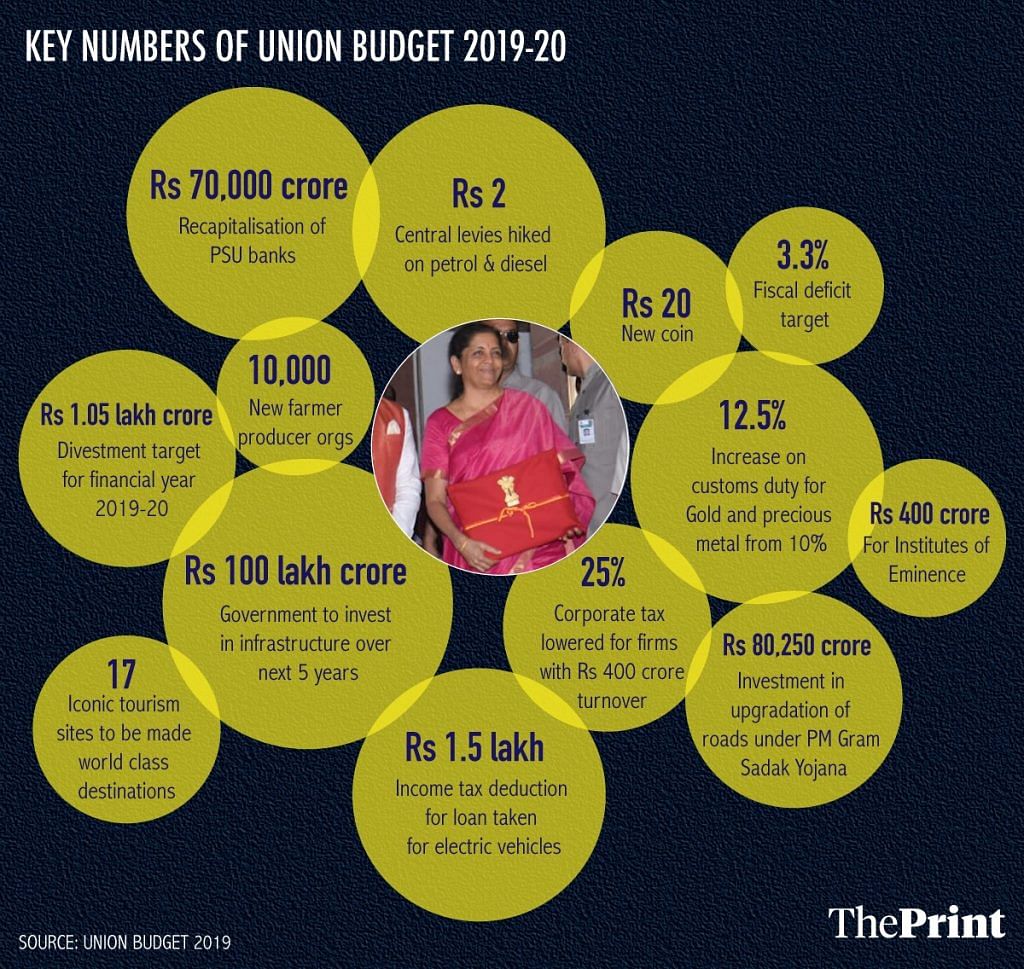

However, if we use the provisional actuals for 2018-19, the budgeted numbers appear too ambitious. The budgeted net tax revenue in 2019-20 is about 25 per cent higher than the actuals in 2018-19. This can be partly explained by increase in tax rates – tariffs, cess on petrol and diesel, surcharge on individuals with higher income, among other measures. GST collections are also expected to be higher this year.

Still, the expected increase in revenue collection is quite ambitious under the present economic conditions. Due to the way the budget process works, it may not have been possible to use the provisional actual numbers while preparing the budget. Because of this, the budget estimates have turned out to be quite unrealistic, and may require significant course-correction during the year. Hopefully, the government will develop a strategy early, instead of making hasty decisions later in the year.

It seems budget management will continue to be challenging in the coming year or even beyond. The government is in an unenviable position of having to deliver on high expectations while being saddled with severe constraints. However, constraints can also create the necessity for reforms.

Also read: Budget 2019 will boost growth only if Modi govt is friendly towards business and profits

Reform & experiment

The constraints may have created the incentive to initiate or expedite expenditure management and asset monetisation reforms that can improve allocative and technical efficiency of government expenditure. In addition to continuing with the reforms in subsidies, welfare schemes, procurement, administrative expenditure, three key areas of reform deserve close attention.

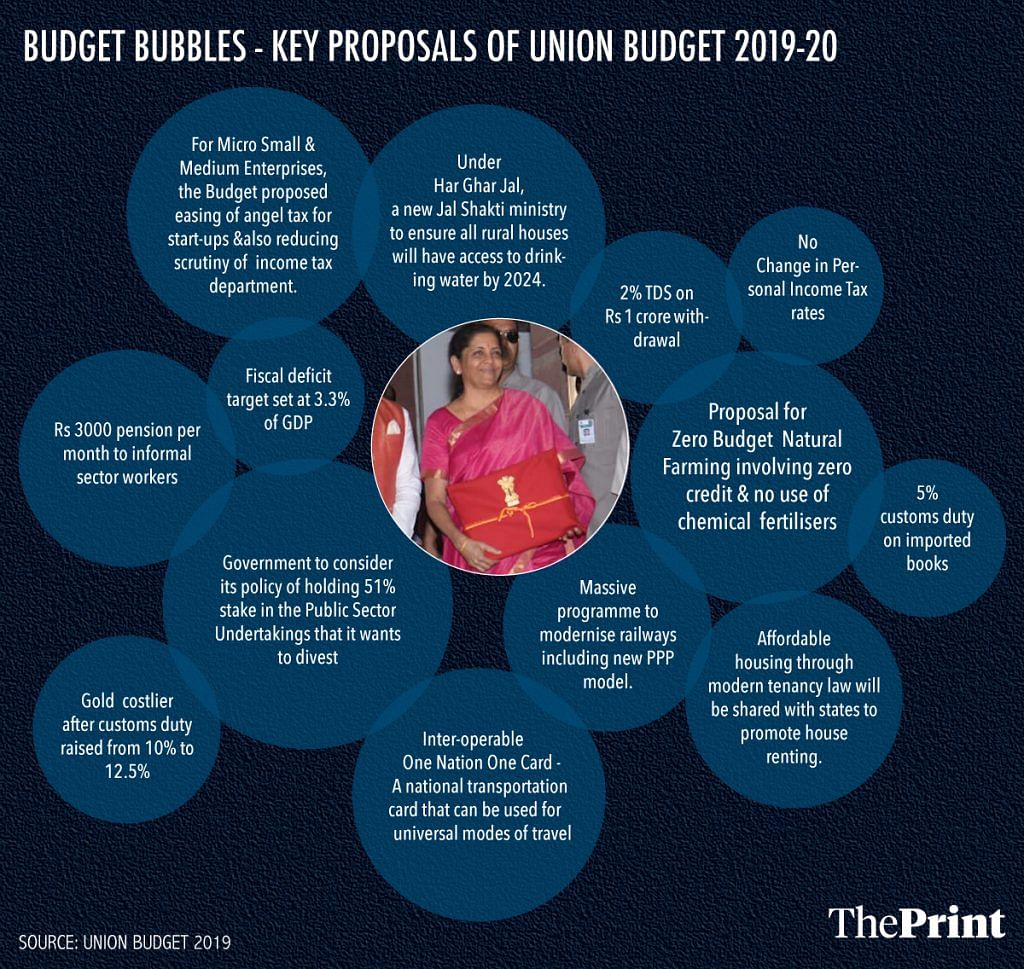

First, the government can tap into its assets (especially shares of public sector enterprises, land controlled by government, and operational infrastructure assets). Privatisation yielded good results when it was last done. It is time to revive the privatisation programme that has effectively been on hold since 2003, in spite of an announcement in 2016 to revive it. In sectors such as railways and power transmission, the private sector brings in capital and perhaps also improves efficiency.

Second, the central government can consider rationalising its role in sectors that are state subjects (like agriculture, land, law and order) by focusing on national public goods. Some of the major sources of increased expenditure in recent years have been in these areas. The expansion of paramilitary forces was necessitated by what were initially law and order problems in states before they became national security threats. The agrarian crisis is creating fiscal demands in the form of income support and price support for farmers. The Centre and the states will have to work in a cooperative manner to prevent such possibilities in the future.

Third, the government should take steps to solve the problem of public sector banks that have turned out to be major claimants of fiscal resources, but cannot be immediately privatised due to fears of instability or high political costs. This will require a long-term strategy, but a beginning can be made by a modern, market-based insolvency resolution law that covers public sector banks.

Also read: Zero-budget farming: Why Budget 2019 isn’t in sync with PM Modi’s promises to farmers

Many of these reforms will not yield results in the short-run, but the present constraints have created the necessity to try different approaches.

The expectation that a democracy would seize such a moment and take the shortest and quickest route to resolve the difficulties is likely to be thwarted by the very nature of democratic politics, which favours gradualism over sudden change, pragmatic tinkering over clearly defined strategies and political expediency over long-term thinking. This is why democracies are endlessly frustrating for certain kinds of analysts and intellectuals.

However, when faced with problems, the strength of a democracy lies in experimenting and finding the right kind of ideas and institutions. The combination of a constrained fiscal situation, a slowing economy, and an extraordinary electoral mandate may provide the impulse for such experimentation.

The author is a Fellow at Carnegie India. Views are personal.

Fine edit in IE today, Incrementalism over Ambition. It points out that subsidies on Food, fertiliser, crop loans and the recent income transfer scheme are now about Rs 3.57 trillion. Also that with India now a structurally surplus producer for several important crops, food inflation flat or negative, restrictions under the EC Act and the APMCs have lost their rationale. It suggests limiting food procurement to no more than fifty million tons a year. 2. One could go further. Why not dismantle the entire edifice of FCI, PDS, immense logistics of procurement, transport, storage of food grains. Direct cash transfers to identified beneficiaries. Farmers will change their cropping patterns to reflect changing dietary preferences. Maybe one took the campaign promises of 2014 too seriously, but these are the sort of initiatives one expected from day one. In the eternal trade off between politics and economics, one never expected the pendulum to swing so far out.