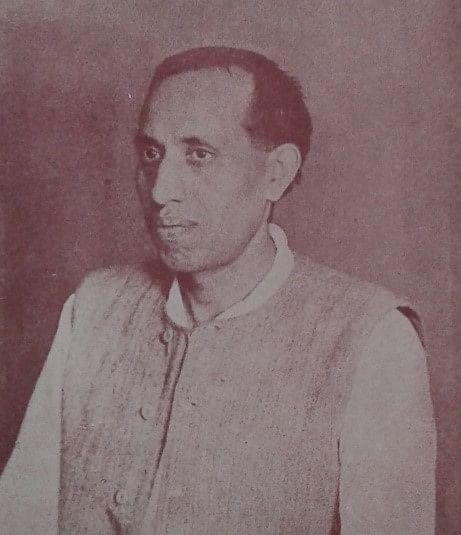

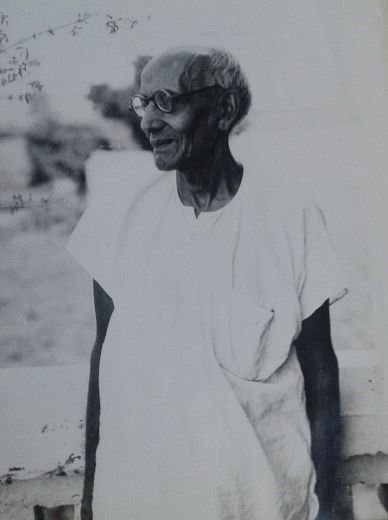

“The basic purpose of communism is to establish Ram Rajya [the righteous reign of Ram] on earth.” This quote by Satyabhakta (1897-1985), founder and organiser of the first Indian Communist Conference at Kanpur on 26 December 1925, exemplifies the inscription of a Hindu communist, who brought on the same page two unlikely ideological companions.

Moving away from an atheist Marxist enlightenment, in Satyabhakta’s rendering a pralay (catastrophe, end of the world) was soon to be expected, an apocalyptic warning of an end to both colonialism and capitalism, at the same time presaging the coming of a utopian communist enclave, a romanticised notion of Ram Rajya, and the unfolding of a future satyug (blissful era of truth) for India.

Inspired in part by Gandhi’s creative use of Ram Rajya, Simone Weil’s Left mysticism (2014), Enrique Dussel’s philosophy of liberation (2003), and Alan Wald’s descriptions of lesser-known dissenting communist writers (1994), this essay, in its attempts to tread the largely unchartered territory of ‘Hindu Communism’, focuses on the imaginative and troubling congruency of communist ideology with a Hindu faith-based ethical morality in the Hindi writings of Satyabhakta, a figure considerably marginalised and maligned in the histories of communism in India.

Also read: Shripad Amrit Dange, the overshadowed beacon of Indian Communism

A figure of lost ‘Hindu Left’

Mainstream Marxism and communism, which operate largely in an atheist, materialist, metaphysical and enlightenment framework, are often hostile to religion (McLellan, 1987), regarding it as an ideological deviation. Many Indian communists and secular historians also complement such atheistic assertions, since they uphold a stark separation between religion and politics. Given the meteoric rise of Hindutva politics in India, they have persuasively argued against the use of Hindu religious symbols or values in the political-public sphere, and made a strong case for Marxist secularism.

While attempting to dismantle militant Hindutva, the resilience and pervasiveness of religious idioms and Hinduism in India suggest that the counternarratives to communalism may not lie in secularism alone. An alternative may be sought in a range of histories and writings between the two, some of which are based on humanist religious terminologies.

Equally, even communism may not be always bound by rules of atheism or shaped by a secular teleology. Liberation theology promoted a fusion between religion and Marxism. However, its focus has been overwhelmingly dependent upon Christianity, and to some extent Islam, Judaism and Buddhism. In comparison, Hindu liberation theology is a neglected field, perhaps because religions like Christianity and Islam have been considered more amenable to Left readings and translations.

Way back in 2002, Ruth Vanita underscored the continuing presence of the Christian Left and the Islamic Left in different parts of the world, and mourned the lack of a Hindu Left, critiquing ‘secular left’s almost paranoid stance on anything that savored of Hinduism’. Satyabhakta complicates such a standpoint, exemplifying a quintessential figure of this lost ‘Hindu Left’.

Satyabhakta not only saw no discrepancy between communism and religious spiritualism, but also actually regarded them as complementary in conceiving a dream of an egalitarian India. Moreover, in exemplifying a strand of vernacular communism, he and some others moved away from a chaste, Sanskritised Hindi, and instead adopted a simple, colloquial, everyday people’s language and vocabulary for their writings and journalism. Yet, unlike some others, Satyabhakta was not only a journalist and a writer, but also an active contributor on the ground, and was driven to establish a formal communist party.

Born as Chakan Lal on 2 April 1897 in Bharatpur, Rajasthan, Satyabhakta, from his early years, was exposed to the weekly Bharat Mitra, Radhamohan Gokul’s Satya Sanatan Dharm and Pratap. He avidly read books like Desh ki Baat, Anandmath, Japan ka Uday, and later, Underground Russia and Nihilist Rahasya. At the same time, his grandfather often narrated tales of ghosts and Hindu mythology to him (Satyabhakta, Marne ke Baad, p. 5). He became well versed in the Puranas, particularly Bhagavata Purana and Garuda Purana, and was deeply attracted towards Ramcharitmanas, considering its impact as widespread as the Bible (Satyabhakta, Sapt Dwip, p. 37).

Also read: EMS Namboodiripad, the communist CM who laid foundation of ‘Kerala model’

Indian traditions and Hinduism in dialogue with Communism

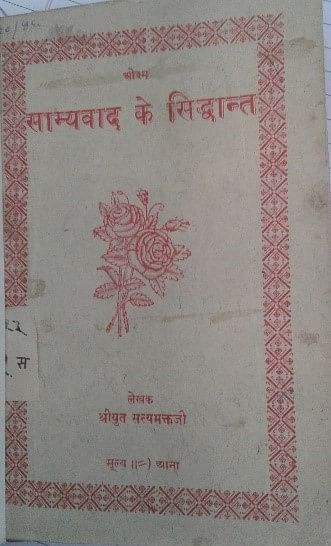

Synthesising two systems of beliefs and values, Satyabhakta saw a congruence between Hinduism and Communism, spiritualism and materialism. Introducing basic Marxist ideas in accessible language, he wrote Samyavad ke Siddhant (Principles of Communism) in 1934. Interestingly, on the cover ‘Om’ was written just above the main title.

Satyabhakta’s spiritualism and his identity as a Hindu and a nationalist thus sat comfortably with his communism. He stated: “While working for the promotion of communism, I kept in mind the specificities and specialities of Indianness and characteristics of Indian culture…. If the Indian public is interested in spirituality, then it is not a mistake to keep this feature in the propagation of communism.”

He felt that the message of communism would be enthusiastically received by people through a framework of Hindu ethics.

Recollecting how communism was relatively new for Indians in the 1920s, Satyabhakta began his book Bharat mein Samyavad (Communism in India): “As such, in our culture, since ancient times, there was a feeling of unity and harmony, which developed and reached the idea that “all people are spiritual”, but it was mostly confined to the metaphysical-ideological field.” Stressing social and humane concerns of Hindu religion, rather than its theological and metaphysical dimensions, Satyabhakta draped communist social equality in the attire of Hindu morality and traditions, and used it to respond critically and constructively to contemporary political issues.

In an attempt to unify his political and religious beliefs, Satyabhakta represented his communism as an epitome of Indianness as well as Hinduness: “Listen to the essence of religion and practice it in your life. What you do not like yourself, do not do it with others. What more could be the principle of communism than this?”

Satyabhakta’s beliefs threw the ‘secular universalism of Marxism into repeated crisis’. Embodying a ‘Left Hinduism’, he selectively took elements of ancient Hindu beliefs and sentiments as models of inspiration, and attempted to reclaim their ethical humane heritage for communism.

Also read: Whose Ram Rajya does Ayodhya temple bring — Gandhi’s or Modi’s? Ambedkar can answer

Communism as a utopian Ram Rajya

Ruth Levitas categorises utopia as IROS, the imaginary reconstitution of society. The genre of utopia often functions ‘as a critique of contemporary society, and often in a transparent way’. As a concept, it often has its ‘religious roots in paradise’ and ‘political roots in socialism’. Moreover, ‘utopian visions are never arbitrary. They always draw on the resources present in the ambient culture and develop them with specific ends in mind that are heavily structured by the present’. Sandeep Banerjee looks at some of the literary imaginations in colonial India, and shows how these ‘counter-colonial spatial imaginaries’ were ‘utopian in their negation of colonialism’ in different, plural and contradictory ways. A necessary corollary of Satyabhakta’s apocalypse was a communist utopian dream, expressed through the idiom of Ram Rajya.

Satyabhakta’s conceptualisation of Ram Rajya is open to ‘appropriation by both power wielding elites and disenfranchised lower orders’. Satyabhakta’s utopia – a new humanity which connected communist ideas of equality and a non-exploitative world to Ram Rajya’s model of happiness – admired both visions, which made communism both more intelligible and more acceptable to a Hindi-Hindu audience.

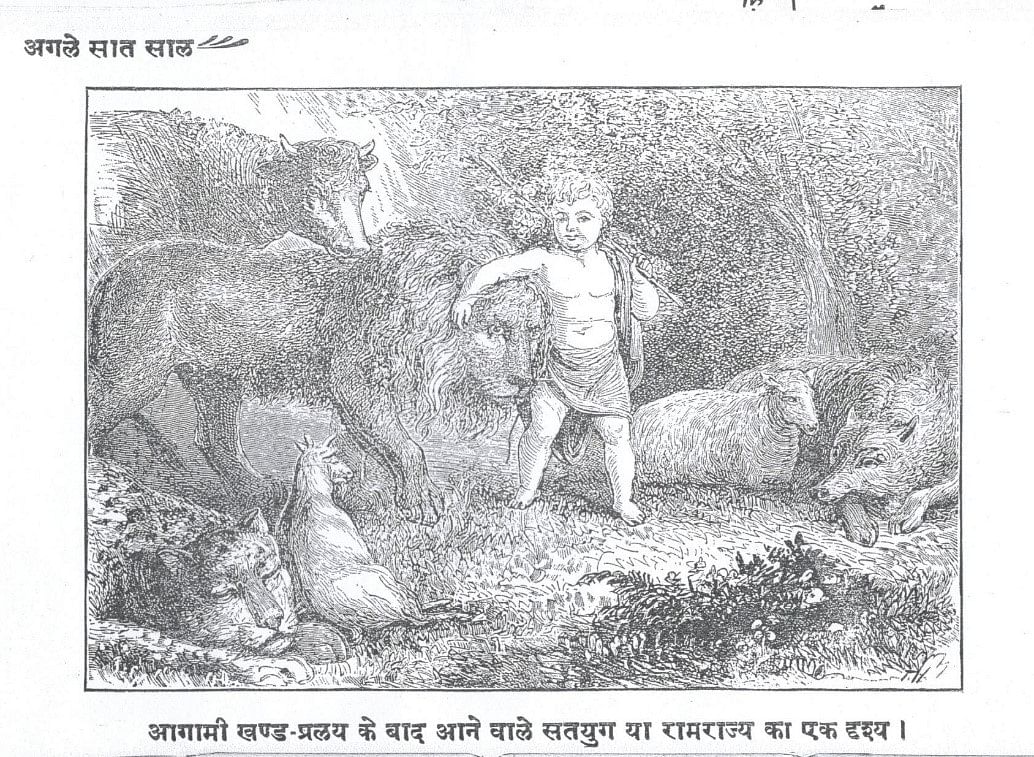

At the same time, from a modernist’s perspective, his utopian idioms were a mixture of religious beliefs and political expediencies that were not confined only to Hindu imaginaries, but were open to drawing from other religions and texts, freely and selectively borrowing from Christian and Islamic asseverations. Writing in 1924, his book Agle Sat Sal listed as the 40th wonder the coming of ‘Ram Rajya or communist rule on earth for a thousand years’, where he even gave an exact date of its commencement – 2 May 1929 or 9 April 1931!

The chapter was accompanied with the following note: “It is written in the Bible that after these seven years, Jesus himself will govern and at that time the lion and the cow will graze together, which cannot mean anything other than communist rule…. These things mean that the rich and cunning men, like the lion of the present time, who fill their stomachs by beating the poor, will…like the poor, have to fill their stomachs through hard work…. The basic purpose of communism is to establish Ram Rajya on earth.”

Drawing from Hindu idioms, the first page of Agle Sat Sal had a picture of a child playing with a lion, and other animals sleeping nearby. The title of the picture stated: Agami khand-pralay ke baad aane wale satyug ya ram rajya ka ek drishya (A view of satyug or Ram Rajya coming after the ensuing catastrophe).

Satyabhakta presented Ram Rajya not as a return or a reversal of history, but as a renewal of a just and more equal past. This signified a long utopian tradition on which future political hopes of an idealised egalitarian communism could be constructed. In his article ‘Ram Rajya ki Adhunik Kalpana’ (‘Modern Imagination of Ram Rajya’), he reinterpreted Ram Rajya by connecting it directly to Plato’s Republic and Thomas More’s Utopia, and extending it to an egalitarian communist dream. Arguing that communism offered the true and modern meaning of Ram Rajya, and connecting myths of a golden past with possibilities of a golden future, the article widened the scope of utopia by proposing a broader and more pluralist vision.

Selectively borrowing from Gandhi’s ideals, but rejecting Hindutva’s exclusivist interpretation, Satyabhakta drew on a classical idea in formulating a language of communism. Ram Rajya was not a symbol of potential alienation or xenophobia, but of hope. Satyabhakta’s leanings towards both – an Indian communist polity and Hindu spiritual ethics – was imaginative and troubling at the same time, since it embodied conflicting messages and ambiguities.

While Satyabhakta sensitively addressed issues of caste and Muslims, two contentious issues in the everyday workings of Hinduism in modern India, in some of his overtly communist writings, he floundered in seeing its contradictions in his works on Hindu faith. The Brahmanical scriptural basis of textual Hinduism, and its principles of hierarchy and exclusion in the formulation of varnashramdharma, were not clearly addressed by Satyabhakta here. (For example, feminist and Dalit discourses have rightly challenged the idea of a utopian Ram Rajya and the victimisation of Sita and Shambuk.) Yet, distinctly different from many Brahmin leaders of the communist movement, Satyabhakta married a Dalit woman, and faced severe social ostracism as a result (Karmendu Shishir, Satyabhakta aur Samyavadi Party, p. 29).

While calling Tulsidas’s Ramayana ‘the soul of Hindi’, he stated that ‘just as a rose, in spite of being beautiful, has sharp thorns…an excellent book cannot be free of errors’, and had to be critiqued for its failings. He firmly objected to its stri jati ke sambandh mein anuchit akshep (unwarranted aspersions on women), and naming of them as dhurt aur kapti (sly and insidious). He castigated Tulsidas for this ‘unmerciful attack’, calling it completely ‘unjustified and contemptible’ (Satyabhakta, Ramayana mein Stri Jati, p. 26).

The entanglement of religious idioms with political rhetoric could unleash complex questions of identity and give rise to multivocal meanings open to divergent interpretations – at times progressive, at times sectarian and ethnic. Yet, for Satyabhakta, as a sublime and ideal polity, Ram Rajya offered a lofty and powerful protest against colonial exploitation. It also provided an anti-capitalist, aesthetic ‘communist’ enclav of spiritual-political ethics which contained unbounded possibilities for the future. Even though precarious, such a simultaneous creative fusion of religion and communism says much about the everyday terrain of popular plebeian desires and communist dreams, where no neat boundaries separate the religious and secular, and the spiritual and material.

Also read: Legal autocrats are on the rise. They use constitution and democracy to destroy both

Conclusion

Neatly defined and circumscribed communist vocabularies of validation and legitimation often perceive the views of figures like Satyabhakta as promiscuous meanderings or distorted versions of communism, as flowing from irrational beliefs, superstitions and religious idioms. It may be argued that people like Satyabhakta were not very sharp intellectually, had ideological limits, and a layperson’s understanding of communism. Satyabhakta’s quixotic apocalyptic prophecies and utopian aspirations often floundered.

Yet, his writings elucidate the need to make Eurocentric Marxist structures of Indian Leftist thought more amenable to cultural moorings, which in his case displayed heavy imprints of cosmologies constructed through ages in the Hindu Puranic world. His thought also suggested that class struggle can coexist with cooperation. Even if fragmented, incomplete and amateur, such understandings did not depend upon borrowed or preconceived notions of communism, but transcended and refashioned them inventively to make them more malleable, and by doing so challenged the criticism that communists were antipathetic to religion.

People like Satyabhakta bore a potential for the realisation of communism and a dream of social transformation far beyond the constraints of the present. Steeped in a north Indian Hindi literary tradition, they illuminated a path of communism that was both distinctly religious and Indian.

Satyabhakta represents a Left politics which provided a bridge between Hindu traditions, spiritual devotion, and a creative blend of religious leanings with communist ethics and Left identities. An intermediary voice between traditional and modern, spiritual and material, communist and nationalist, in Satyabhakta’s interpretations, these were not competing or antagonistic discourses, but complementary to, and mutually constitutive of, each other. Figures like Satyabhakta represent a complexity of layered nuances, hidden transcripts and forgotten histories of communism in north India. Even if flawed and partial, they bequeath cultural and political legacies that suggest the rich and pluralist imaginings of communism, far removed from the monopolistic single-mindedness of its official and dominant practitioners.

Charu Gupta is a professor of history, University of Delhi, and did her PhD from SOAS, London. Views are personal.

This is an edited excerpt from the author’s paper, ‘Hindu Communism’: Satyabhakta, Apocalypses and Utopian Ram Rajya, first published in The Indian Economic and Social History Review (Vol 58, Issue 2), SAGE journals. Read the full paper here.

(Edited by Prashant Dixit)