Raipur/Jashpur/Bastar: Until the early 1980s, Madhvi Joshi was a junior college teacher in Nagpur. Her husband Nishikant Joshi also had a government job and, when a baby came along in 1981, their life seemed complete. But just as their son turned one, the couple resigned from their jobs and left for Assam as full-time workers of the Vanvasi Kalyan Ashram (VKA), an affiliate of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) that works among tribal communities across the country.

It was the calling they had been waiting for.

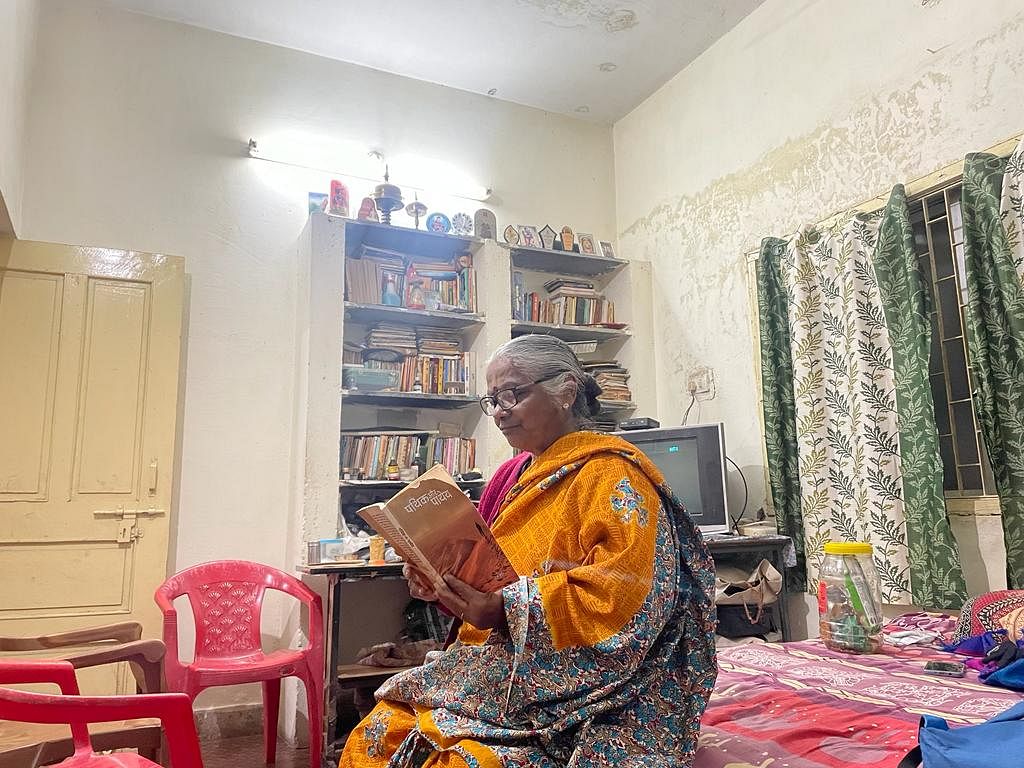

“We did not have a mission in our lives until then,” Madhvi, now in her 70s, said, speaking to ThePrint in Chhattisgarh. “Working for the janjati samaj (tribal society) gave us that.”

After 10 years in Assam, the Joshis were sent to Bastar in Chhattisgarh — then a part of Madhya Pradesh. A hub of the Maoist insurgency, the district has a tribal population of over 70 percent.

It’s not just Bastar. Chhattisgarh is home to approximately 7.5 percent of India’s tribal population, and tribals constitute about 30 percent of the state’s population.

Members of the VKA and RSS say the organisation’s work was crucial to the BJP’s victory in the 2023 assembly election, as also its defeat in 2018. That election, VKA cadres had refused to campaign for the BJP as they felt it had done little to stop conversions of tribal communities to Christianity in its tenure from 2003 to 2018.

“The dharmantaran (conversions) continued unabated, and all they (the BJP government) would do is come up with bureaucratic excuses,” said a senior VKA functionary.

For a party that makes no bones about its stand on conversions and Hindutva, this was seen as unacceptable.

Raman Singh, who was the chief minister throughout those 15 years, was known for his policies like his widely-emulated public distribution system or the Chhattisgarh Health Service, but he was seen to have failed on this count.

Singh, VKA leaders said, was no Yogi Adityanath (Uttar Pradesh CM) or Himanta Biswa Sarma (Assam), two leaders who are lauded in the Hindu Right for walking the talk on conversions.

When 2018 came around, the sentiment in the Chhattisgarh-headquartered VKA was: “Let them lose this time.”

It was a telling sentiment from an organisation that calls itself apolitical.

The ‘apolitical’ political agents

Established over seven decades ago, the VKA is a quintessential RSS affiliate.

Its workers — highly motivated, dedicated, decades-long volunteers — see their work as a divinely ordained mission.

According to the VKA’s website, they have an all-India network of 15,000 villages and 1,300 full-time workers. But insiders say the actual numbers are much higher.

They work in the domains of health, education, skill development, and culture.

Across the tribal-dominated states — especially in the northeast, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, and Gujarat — the VKA runs hostels for poor tribal children, skill development centres, clinics, hospitals, schools — sometimes the schools, ekal vidyalayas, are run by a single teacher because the areas they operate in are so remote.

But their moot motivation remains to bring — or “bring back”, as they believe — India’s diverse tribal communities into the Hindu fold.

They do so through patient, often-painstaking, and systematic socialisation of the tribal people.

As a senior RSS functionary from Chhattisgarh put it, their work creates a base of “committed voters”— those who are committed to the Hindutva cause, and would never swing to the other side.

The idea is to keep expanding this base — losing an election here or there matters little in the larger scheme of things.

“Rajneeti sthayi nahi hoti… Hum jo kaam karte hain woh sthayi hai — vyakti ko andar se badalta hai (Politics is not permanent. What we do is permanent — it changes a person from within),” said Madhvi, speaking to ThePrint in a large hall with cracking walls and flaking paint in the Shabri Kanya Ashram.

Located in a quiet, lush green complex in the capital city of Raipur, the hostel houses 37 tribal girls from the northeast.

In the Ramayana, Shabri is described as a devotee of Lord Ram and member of the Bhil tribe.

The VKA’s tribal-outreach thrust includes trying to link the tribal society to mainstream Hinduism — so, the tribal women are equated to Shabri, while men are equated to Hanuman. To them, the tribal society at large is Rama’s “Vanar Sena”.

According to an article in the RSS weekly Organiser, the VKA was established for a twofold reason: “To bring back those tribals who were converted to Christianity by fraud, allurement or some other means and to inculcate in them a strong sense of belonging to Indian culture and religion.”

Stopping religious conversion is the raison d’etre of the organisation.

The beginnings

The VKA was established on 26 December 1952, in the hilly town of Jashpur — located almost 500 kilometres from Raipur in northern Chhattisgarh — against a backdrop of “unabated conversions” that were allegedly continuing even after the formal transfer of power from the British crown to the Indian government.

A few months earlier, Balasaheb Deshpande, an RSS swayamsevak and government servant from present-day Maharashtra, was posted to Jashpur as the regional officer of the Tribal Development Scheme by the then Madhya Pradesh chief minister, Ravishankar Shukla, to check the “rampant conversions”.

A local RSS leader said Shukla, a Congress leader, was as concerned about religious conversions as M.S. Golwalkar, the then RSS sarsanghchalak, adding ruefully that “the Congress used to be sympathetic to Hindu causes in the immediate aftermath of the Partition”.

The rest of the story is narrated near verbatim by anyone you speak to at the VKA.

“Bohot gambhir stithi thi — har taraf Ishu ka naam tha, samaj apne se kat raha tha. Ek alag isai rashtra banane ka bhayanak sharyantra chal raha tha (It was a very serious situation — Jesus’ name was everywhere, and the society was getting cut off from its roots. There was a terrible conspiracy to carve out a Christian state).”

Health and education here were barely government subjects — they were missionary subjects, they say. Even the government could not break the missionary monopoly.

The result, according to the VKA, was mass conversions to Christianity through seemingly apolitical social work.

As regional officer, Deshpande opened 100 tribal schools in one stroke — but they never took off.

When a despondent Deshpande approached Golwalkar with the developments, the path ahead seemed clear for the latter: Deshpande needed to quit government service, and start an organisation to “bring back” tribal society into Hinduism.

Deshpande, a Marathi Brahmin from Nagpur, was thus given the mammoth task of spreading Hindutva among India’s tribal people.

“VKA started in this very palace where we are sitting, by my grandfather and Deshpande ji,” said Ranvijay Singh Judeo, a BJP leader and scion of the former royal family of Jashpur, talking to ThePrint in the Aaram Niwas Palace on a chilly December day.

The relatively small palace, which is surrounded by forests and hills, is filled with royal Rajput nostalgia.

The walls are packed with old black and white pictures of maharajas and princes brandishing their guns and lording over corpses of felled tigers, boars and bears. Other photographs show the royals posing in their Rolls Royce cars.

Judeo’s grandfather, the former maharaja of Jashpur, Vijay Bhushan Singh, was one of VKA’s earliest patrons — he even brainstormed the name of the organisation with Deshpande.

The name decided upon — Vanvasi Kalyan Ashram — is crucial to its ideology.

The RSS does not use the term ‘adivasi’ for India’s tribal people. ‘Adivasi’ refers to an individual who has inhabited a place since the beginning (adikaal). For the RSS, conceding this amounts to a rejection of their long-held stand that the autochthons of India were the Aryans of the Vedic time.

They prefer the word ‘vanvasi’, which simply means forest-dwellers. To them, the terms ‘tribal’ or ‘adivasi’ are the products of a British tactic to divide the Hindu society.

They are not entirely wrong.

Like for the rest of the country, the British created detailed banks of colonial knowledge about the tribes. Several postcolonial scholars have argued that it was the British who constructed the category of ‘tribe’ in the first place, to describe all those who lived in inaccessible forests and hills.

In the process, the scholars say, they unified a disparate range of people scattered across the country into a unified bureaucratic grouping.

Perhaps more damagingly, colonial knowledge distinguished this construct from the rest of the “civilised society”.

However, the word ‘adivasi’ was not a British construct.

Disparate tribal groups chose the word themselves around the 20th century to identify themselves in order to assert their indigeneity.

According to Gail Omvedt, the famed US-born Indian sociologist, the adivasis were part of the 1920s and 1930s “adi” movements across the country — along with Adi-Dravidas, Adi-Andhras, Adi-Hindus, and Adi-Dharm.

“All of (these) had a common ideological claim of being original inhabitants who lived in a society of equality until subjugated by invading Aryans with their caste system,” she wrote in a review of historian David Hardiman’s book, The Coming of the Devi: Adivasi Assertion in Western India.

For the VKA, such an assertion is ideologically problematic. Their motto itself seeks to refute it — “tu, main, ek rakht (you and I have the same blood)”.

According to Judeo, Christian missionaries first arrived in the area in the late 1700s.

“Until then, this area was all Hindu… By the 1900s, there were churches everywhere — the whole demography had changed,” he said.

Vijay Bhushan Judeo, who eventually joined the Jana Sangh, gave the VKA 3,000 acres of land in Jashpur to start the ashram. Like the RSS, he believed the widespread “dharmantaran (religious conversion)” could not be checked legally and needed to be tackled systematically, through philanthropy.

Hostels, hospitals, Ramayana and bhajan mandalis, sanskar kendras, door-to-door awareness campaigns, distribution of Hanuman statues and lockets to children — all began with one goal: to make tribal people, who had ostensibly been misled by the missionaries, “rediscover” their Hindu origins.

Also Read: Inside ‘Ghar Wapsi’ of Chhattisgarh tribals: RSS women priests reach out, royal washes feet

A mirror image of the missionaries?

Gradually, as the VKA began to spread across different tribal areas, they increasingly started looking like a mirror image of the missionaries.

In order to stop conversions to Christianity through medical services — many local residents, including Christians, told ThePrint that most people convert when they are “helped” in sickness — and educational institutions, the VKA came up with their own health and educational institutions across the country.

Much like the missionaries who first brought in foreigners to do the work of the mission among the tribes, and eventually inculcated leadership from within the tribal communities, the VKA’s leadership too initially comprised Brahmins from Maharashtra and Kerala. Now, the organisation boasts of a sizeable tribal leadership.

At VKA-run schools, the curriculum includes the formal syllabi set by the state education board, as well as dharmic (religious) education.

The VKA has not been able to outdo the missionaries in building a strong healthcare system as yet. While they have built hospitals in a few areas, in some of the remote places, they appoint aarogya rakshaks, who are trained in basic healthcare services.

Several government schemes meant for tribal areas are implemented with their assistance. They actively hold dialogues with government ministries and routinely make policy-level interventions. “They act like a local NGO,” said a Christian social activist from Raipur.

In Chhattisgarh alone, the VKA runs 14 hostels, where tribal children, who do not have educational opportunities in their villages, live free of cost. The Shabri Kanya Ashram is one of these 14 hostels.

The girls here, mostly school-going adolescents, have a packed day. They wake up before sunrise and assemble for jagran prarthna, their daily prayers, followed by yoga, including suryanamaskar.

They then come together for a Ramayana path and svadhyay, which roughly translates as the self-study of the Vedas and other Sanskrit texts. Then they proceed to their school — a Saraswati Shishu Mandir less than a minute away from the hostel.

The Saraswati Shishu Mandirs are a network of RSS-run schools across the country.

According to historian Tanika Sarkar, the reason these schools are called mandir or temples is because the RSS feels that the true national education teaches the student to be proud of his/her Hindu heritage.

Madhvi refutes this claim, at least when made overtly. The VKA never imposes Hindu-ness on tribal children. “We never tell them they are Hindu,” she said. “But as a matter of fact, they are.”

Outside the hall where she is sitting, the girls begin to congregate for their evening shakha. Soon, they line up in front of a saffron flag and begin chanting Sanskrit shlokas. After the drill-like assembly, it is time for play.

The girls break into two groups — one playing kabbadi, the other, tug-of-war. A few girls are learning archery from two older boys, who are also from VKA. “We make children across all our hostels play Bharatiya sports, not cricket or football,” said Madhvi. “Khel-kood bhi rashtravaad ka zaria hai (play is also a means to inculcate nationalism among children).”

The hour-long play session is halted by a bell. The girls rush to their rooms to freshen up. In less than ten minutes, they have gathered in a hall on the first floor. They sit cross-legged in front of a small mandir.

There are framed pictures of Ganesh, Shiv, Saraswati, and Mira Bai in the mandir. In one picture, Shiv is embracing Hanuman. The girls begin to sing bhajans in Hindi. The most easily identifiable of them is “Om Jai Jagadish Hare”.

As they conclude the aarti, the girls chant in unison: “Jai Jai Shri Ram”, “Bharatiya sanskriti ki jai (hail Indian culture)”, “Hindu dharma ki jai (hail Hinduism)”.

Much of the infusion of mainstream Hinduism into tribal customs can be traced to what scholars describe as “invented traditions” — for instance, the VKA claims that Budha Dev, a local tribal deity worshipped in parts of Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand, is a manifestation of Lord Shiv, while many from the tribal community refute any such connection.

But this trend predates the VKA — and started with the colonial ethnography and census operations of the British.

For instance, Bhangya Bhukya, a historian at the University of Hyderabad, wrote of a census official who equated a tribe in the Nilgiris to the Pandavas because they had a custom of marrying several brothers to one woman.

The same official, Bhukya wrote in an essay titled ‘The Mapping of the Adivasi Social: Colonial Anthropology and Adivasis’, compared the wedding ceremony of another tribe in Odisha’s Ganjam to Krishna’s romance with Rukmini because the custom involved the boy “capturing” a girl when she went to the stream to fetch water before marrying her.

This writing, which had the credence of being “official”, was then inherited by those who believe the tribals were originally Hindu.

Assimilating the tribes

As a result of more than a century of this assimilation effort, mainstream Hinduism has now become ubiquitous across Bastar and Surguja.

Local residents say festivals like Ganesh Chaturthi, Durga puja, Navratri, Saraswati puja were unknown in tribal villages even until a decade and a half ago. But now, they are routinely celebrated.

“You see tribal people playing garba in Bastar now… it would be laughable if not so worrying,” said the Raipur-based activist, who didn’t wish to be named. “People are growing up thinking they are being traditional, while the traditions themselves are invented.”

Alok Shukla, another Raipur-based activist whose work takes him to tribal villages almost every week, agreed. “The thing about the RSS-VKA is that they keep inducing these festivals, rituals, generation after generation… Gradually, there comes a generation which has simply grown up seeing these as their own culture,” he said.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, it was the television that aided this project.

Tribes of Bastar and Surguja watched the Ramayana and Mahabharat along with the rest of the country in the 90s, with the VKA and the RSS organising communal viewing events in villages.

This was also the time when violence against Christians on the pretext of “beef-eating, excessive alcoholism, and seducing non-Christian tribal women” started becoming commonplace.

In the 2020s, the all-pervasive internet is serving the same purpose.

An all-male group from the Sarva Adivasi Samaj, a statewide tribal organisation with a significant following, said young people and women are especially susceptible to falling for the “Hindutva propaganda”.

“They receive messages on WhatsApp saying ‘light 1,000 diyas, you will get this’, or ‘observe a fast every Tuesday, you will get that’,” said Ramlal Usendi, a leader of the group.

Hindu rituals thus become family rituals, members of the group added, saying it is also a function of aspiration. “Hindu dharma is fashionable now,” said one. “Everyone wants to belong to the mainstream… Nobody aspires to be a perennial minority.”

The more educated a person is, the more “Hindu” they want to be, the member added, with the rest of the group members nodding in agreement.

As the team gathers in their open-air office in the Narayanpur district of Bastar region to celebrate a local festival marking the harvest of urad dal, a group of people on the premises slaughters a goat for ‘prasad’.

The Sarva Adivasi Samaj is headed by the vastly popular octogenarian leader Arvind Netam, who was with the Congress through his political career before quitting earlier this year.

This election, he floated his own party — the Humar Samaj Party. Netam, who belongs to Jagdalpur in Bastar, said the tribal community and identity is being sandwiched between Christianity and Hinduism. Everywhere you go, you either see Hanuman temples or churches — both are alien to the tribal society, he added.

“To make us either Sanatani or Christian is an obliteration of our culture,” Netam said.

The politician, who first became a minister in Indira Gandhi’s cabinet in 1973, spoke with a kind of urgency in his voice. “We don’t have a God, hum nirakar hain (we worship the formless). Hanuman is not our devta. Sanatan and tribal rituals are completely the opposite,” he added. “We have burials, they have cremations; we don’t have pandits, our pheras are anti-clockwise; after our ancestors die, we embrace their souls inside our homes and they become our family or village gods; we eat meat, we drink alcohol,” he said.

Indeed, several tribal customs are met with disdain by members of the Hindu Right.

In her ethnographic study on Hindu nationalist mobilisation among tribes in Chhattisgarh, anthropologist Peggy Froerer wrote that practices such as propitiation of village and forest deities with alcohol and blood offerings are seen as “backward” by the RSS.

“Such customs described by locals as dehati (rural) Hinduism, are contrasted to the forms of worship found within mainstream, sahari (city) Hinduism, where the ‘big Gods’ — Ram, Shiva — are worshipped with offerings of incense and flowers,” she wrote.

Notably, all VKA schools and hostels are 100 percent vegetarian.

Also Read: Tribal vote swings to BJP in 3 states, decisive in Chhattisgarh victory

The one-off immediacy of elections

Even as the VKA in tandem with the RSS continues to work silently to make long-term inroads into the tribal communities, sometimes the work is infused with a carefully planned sense of immediacy.

In November 2022, RSS Sarsanghchalak Mohan Bhagwat made a four-day visit to Chhattisgarh, where he stayed in Jashpur, at the VKA headquarters.

During his visit, he unveiled a statue of the late BJP leader and former Union minister Dilip Singh Judeo, who was Vijay Bhushan Singh Judeo’s son.

Dilip Singh Judeo, who served as a minister in Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s government, had started the ‘ghar wapsi’ campaign — as efforts to “bring back” converts are called among groups of the Hindu Right — in Chhattisgarh.

Known to have been charismatic and widely popular, Dilip Singh would wash the feet of those who had converted to Christianity in highly publicised events, and facilitate their “re-entry” into Hinduism. The unveiling of his statue in the lead-up to the state elections by the RSS sarsanghchalak himself removed any ambiguity that there might have been regarding the election agenda — conversion had to be a central issue of the campaign.

Across the region — through village-to-village and door-to-door mobilisation, and concerted social media campaigns — non-Christian tribals were warned of a “change in strategy” by missionaries to convert people. Dharmantaran became a buzzword.

Organisations affiliated to the Hindu Right warned non-Christian tribal communities about the emergence of “crypto-Christians”, who convert to Christianity, but do not officially register the conversion.

According to VKA members, they warned them that missionaries now wear saffron robes, hold hawans inside churches, and wear rudraksha malas to make themselves less noticeable — but all allegedly with the motive of converting everyone to Christianity, and “break up” the Hindu society.

The increased religious polarisation is believed to have triggered attacks on the Christian community and clashes in at least 15 villages across Narayanpur in Bastar, with more than 400 tribal church-goers allegedly beaten and forced out of their homes in December 2022 and January 2023.

But as the unnamed VKA functionary pointed out, the conflict — what he referred to as a ‘sangharsh ki sthiti (situation of struggle)’ — is only a result of “the hitherto unaware tribal people understanding the threats to their identity and culture”.

The “innocent and undiscerning tribal” is a common refrain in Chhattisgarh — the missionaries, the Hindu Right organisations, and, sometimes, the tribal people themselves, repeatedly say that they are easily manipulated due to their “innocence” and lack of exposure. Politics in the tribal belts of the state happens as a corrective to this alleged ignorance.

One such “corrective” adopted by the Hindu Right before this election was “delisting”, an issue raised in big rallies across different districts. They believe that a person belonging to a community listed as a Scheduled Tribe (ST) should cease to get reservation benefits if they convert to Christianity or Islam.

This, it is argued, is a perfectly constitutional demand, and in sync with the reservation provisions for Muslims and Christians, whose Scheduled Caste members are not eligible for reservation either.

The issue was first raised as early as the 1960s by a Congress leader, Kartik Oraon, but never taken up seriously by his own party.

“Anyone who converts to Christianity loses all ties with their tribal customs and traditions that make them tribal to begin with. Why should such a person get reservation benefits then?” said Bhojraj Nag, a former BJP MLA from Antagarh, a town in Kanker district of Bastar, and state convener of Janjati Suraksha Manch (JSM), the organisation at the forefront of the delisting campaign.

Founded in 2006 in Chhattisgarh, the JSM has been raising the issue of delisting across the country. Over the last two years or so, they have intensified their campaign significantly.

In April 2022, the JSM held a massive rally in Narayanpur to raise the issue.

According to Nag, the rally was attended by thousands of people from 110 villages across the state. In the subsequent months, rallies were held in ten other districts, and the slogans raised there — recounted by Nag — left little to imagination.

They included, “Kul devi tum jaag jao, dharmantarit tum bhag jaao (family deity awaken, those who convert get out)” or “Jo Bholenath ka nahin, woh hamari jaat ka nahin (one who is not with Bholenath is not from our community)”.

Consequently, several rallies were held across the state by Christian tribals opposing delisting, making the issue a major factor in this election.

“The issue had a major impact in these elections,” said Ramnath Kashyap, a VKA functionary and member of JSM from Bastar.

The now “constitutionally-aware” tribal community has realised it has been shortchanged — it wants its constitutional rights, Kashyap declared.

But RSS leaders say they are in no hurry. They are looking at this issue as a long-term one “just like Article 370 and the Ram Mandir”, which may require awareness and campaigning for years before it actually fructifies.

Meanwhile, through its hostels and schools and cultural programmes, the Vanvasi Kalyan Ashram will keep the groundwork going.

This is an updated version of the report

(Edited by Sunanda Ranjan)

Also Read: BJP’s social engineering in Chhattisgarh: Tribal CM with OBC & Brahmin deputies