Kaithal: There are no photos of the murdered 21-year-old woman from Balu village in Haryana’s Kaithal district. It’s been less than a month since she was hastily cremated, but her uncle can’t seem to recall her name. “What’s her name? What’s her name? I just can’t remember,” he says. Her parents named her Maafi, a plea to the gods to forgive them for their sins so that their next child would be a boy. And now they are in jail, accused of murdering her. She defied them for love—a crime punishable by death.

Villagers are riled not by the woman’s alleged murder but by the fact that her parents, Suresh Kumar and Bala Devi, have been locked up in jail since mid-September and their ‘delayed’ bail. The police allege that they covered up their daughter’s murder.

“What will parents do if their daughter is trying to flee with a man? Let her go,” asks a village elder. Another man sitting opposite him commiserates. “The Kumars did it out of anger. They must have warned her and she was not ready to listen. Now, they are suffering in jail.”

The couple was about to flee. The man had come to her village on his bike on 14 September afternoon. They were so close to freedom. He was kick-starting his motorcycle when her mother came charging out of their grocery shop and caught hold of her dupatta, pulling her off the bike. The man fled. The mother dragged her inside the house, and along with her husband choked their daughter with the dupatta till she stopped struggling. The boyfriend, Rohit Kumar, is still missing, claims his family.

Nobody in the village approved of their planned marriage and the couple had to be punished. But this latest so-called Haryana ‘honour killing’ saga isn’t about inter-caste or the same gotra, or even a same-village union. Both of them were Dalits, but had breached caste in their own way—the woman was a Chamar and the boyfriend was a Dhanak.

What will parents do if their daughter is trying to flee with a man? Let her go?

-Village elder

The brutal slaughter of Kaithal’s daughter is the latest in the unending assault on young people’s rights in Haryana that has been bitterly fought for over two decades now. Everything from chow-mein to smartphones to social media has been blamed for romantic love and runaway couples. But at the heart of it is the social anxiety among parents unleashed by expanding women’s freedoms.

In Haryana’s villages, the practice of giving names like Maafi, Batheris (too much) and Kafis (enough) to unwanted girls is still common.

Catchy slogans of Beti Bachao and Beti Padhao stop at just that and don’t tolerate the breaching of strict cultural boundaries laid down for young women. The sex ratio at birth is once again on the decline, and gender discrimination tests still are conducted on the sly. Education and panchayat reservation have had little impact.

“In sociology, we often say that if we have a number of factors —political empowerment, economic empowerment, education— things will change for women. But Haryana serves as an example that this change is not happening at all,” says Reicha Tanwar, director, Women’s Studies Research Centre at Kurukshetra University.

Also Read: Chances of an inter-caste marriage go up if groom’s mother is educated: Study

‘Women are a source of pride’

Every evening at six, around 12 men from Balu village in Haryana’s Kaithal district gather outside the father, Suresh Kumar’s grocery store. Sitting on rickety chairs and benches they pontificate over the fate of their grocer and his wife.

At first, the parents claimed the death was a washing machine accident; then villagers intervened and said it was a case of suicide.

“The girl, unable to bear the shame her actions caused, took her own life. Now, the parents are paying the price for the sins of their daughter,” declares the sarpanch, 29-year-old Sahil Balu, a practising lawyer.

He’s brimming with righteous anger. But like the others, he finds it difficult to keep up with the stories they have created. He quickly forgets about the suicide.

“In our Haryana, a woman is a source of pride for us. The parents of the daughter were helpless. The young man dared to challenge the entire village by attempting to elope with our daughter, that too in the broad daylight,” he says.

As the men discuss the family, Suresh Kumar’s younger daughter Siya is forced to pretend that nothing has happened. She runs the store under the watchful gaze of her uncle and silently serves them cigarettes, chips and cola.

The young man dared to challenge the entire village by attempting to elope with our daughter, that too in the broad daylight

-Sahil Balu, sarpanch

She leaves the men to go to the washroom. Alone and away from the judging eyes, she cries. “They cannot see my tears,” she says, wiping her face furiously before returning to the store.

Hidden love

In the next village, Gitika* couldn’t eat when she heard of her friend’s sudden, unexplainable death. They are the first generation of women in their families to go to degree college. They study in the same class, and like Maafi, Gitika has a secret boyfriend too, whom she met on Facebook. He is a Dalit from Bhiwani, and she is a Jat. Now, she is planning to break up with hm.

“Maafi was just like me. It can happen to me tomorrow,” says Gitika.

Love unfolds in secret in Haryana—through Instagram DMs and under the cover of trees on deserted streets. After class at Kapil Muni Women’s College in Kaithal Kalayat, Gitika and Maafi would walk to the eucalyptus tree on campus, put the mics of their earphones close to their mouths and call up their boyfriends. They would often smile at each other, but then quickly slide their phones in their bags when their parents arrived to pick them up.

Now Maafi is gone, and the truth that Gitikia always knew but never acknowledged has hit her like a tonne of bricks. Love can set you free but also get you killed.

“I am planning to sever all ties with my lover. He said that we should fight for our love, but no, I am not ready for that now,” says Gitika. She can’t imagine talking to her boyfriend under that tree without Maafi anymore.

Her death has sent a ripple of unease among other women in the college too.

Weeks later, dozens of female students are strolling under the shade of the campus trees murmuring into their phones; their leisurely movements belie their desperation and heartbreak.

Maafi was just like me. It can happen to me tomorrow

– Gitika, Maadi’s friend

Some are saying goodbye to their lovers, others are warning their boyfriends to be careful.

“I won’t be able to talk to you when I reach home. Don’t call me. The phone won’t be with me today,” whispers one woman.

Another woman hastily puts her phone down on seeing her father arrive at the campus gates on his two-wheeler.

“My father has come. Don’t call now,” she says.

This is the only time when they can speak to their lovers, they say jokingly. Many of them have to return the phone to their parents once they reach home. Others have a big brother constantly poking his nose into their business and checking their phones.

Another girl sits on a fallen tree branch. Her name is also Maafi, and she is getting married in a few months. She has only seen her future husband’s photo on her father’s phone.

“He is a 12th pass but has seven acres of land in his name. Land is the only thing that matters when it comes to marriage,” said Maafi, not sure whether she will be allowed to study further. She is yet to meet her husband in person and may only get to do so on her wedding day

“If you look from afar you will see Haryanavi women working, participating in sports, driving cars and scootys. But look a little closer, and you will find these women don’t have any choice,” says Tanwar.

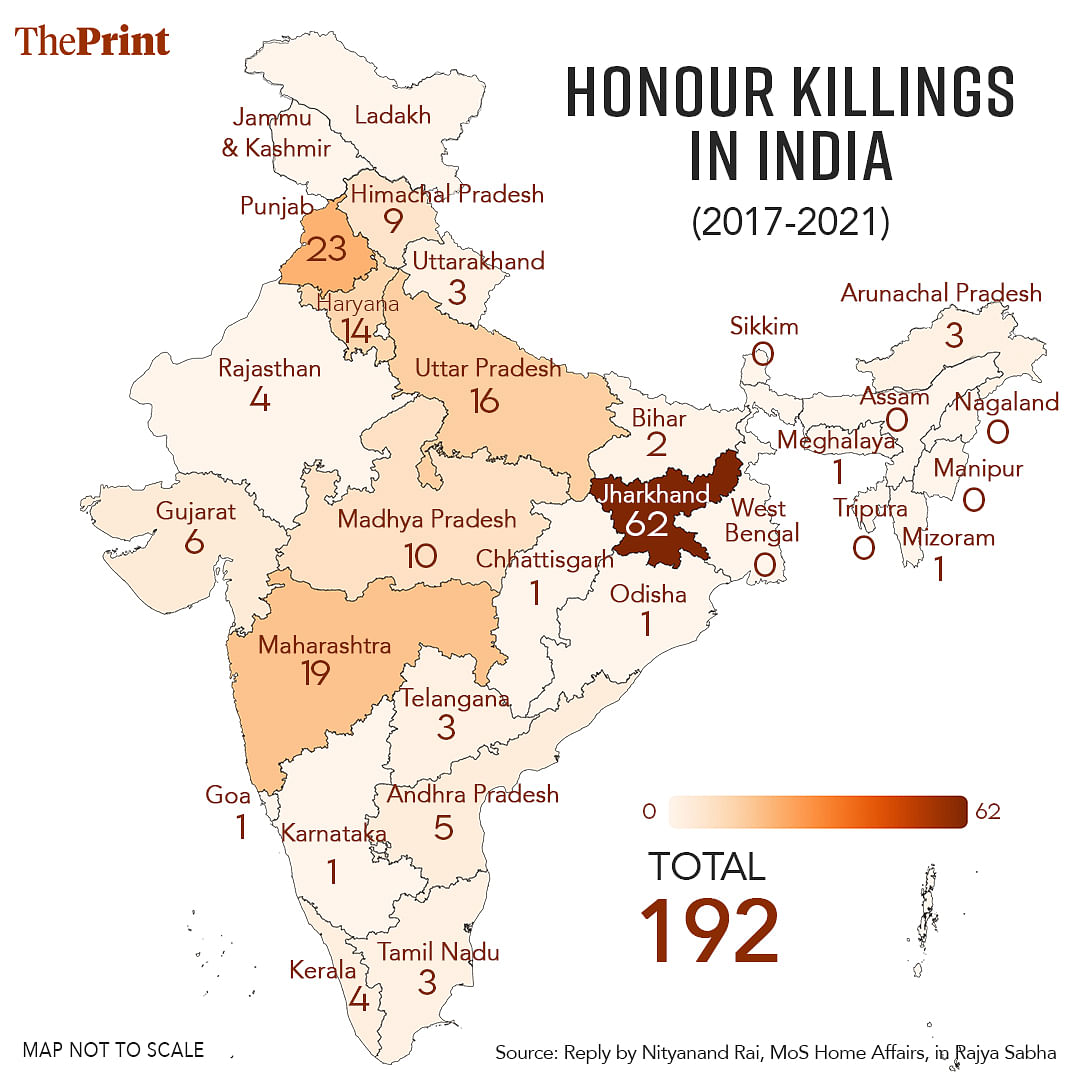

According to response in Rajya Sabha by Nityanand Rai, Minister of State for Home Affairs, in April 2023 Haryana has recorded 14 ‘honour killings’ between 2017 and 2021.

But activists dispute this number. “This data is not representative of the honour killings in Haryana. The government has not enacted the law for honour killing. So they go unreported. Only a few make it to the media,” says Jagmati Sangwan, social activist.

Back in Balu village, some 13 km away from Kapil Muni Women’s College, the men discuss the murdered woman. Maafi’s birth may have been a “mistake”—as some of her family members put it—but she conformed to traditional ideals of beauty.

“She was fair, with wide eyes and a beautiful smile. Her beauty was a source of worry for her parents. Kumar was often worried that men would try to “trap her,” says a villager who did not want to be named.

But Maafi wanted to study more. She wanted to get a college degree. So three years ago, her parents allowed her to enrol in the women’s college. Kumar would drop her off at the college in the morning and pick her up at noon every day on his motorcycle.

If you look from afar you will see Haryanavi women working, participating in sports, driving cars and scootys. But look a little closer, and you will find these women don’t have any choice

– Reicha Tanwar, director, Women’s Studies Research Centre at Kurukshetra University

Kumar was always scrutinising everyone around her for suspicious behaviour, and signs of love, say the villagers.

“But yet, she fell into the trap of a boy. She knew that her parents and no one in the village would approve of any such association,” says Krishan Kumar, Maafi’s granduncle.

Also Read: Stolen glances to stolen lives: Stories behind the ‘honour killings’ of Rajasthan, Haryana

Caste within caste

Maafi and Rohit’s love story began with a ‘hello’ on Instagram. In one year, their fledgling friendship evolved into love. She would video call Rohit secretly when her parents were not around. And he would send her small gifts such as a bangle through common friends all the way from his village in Hisar some 100 km away.

Gikita and other friends say they may have met a few times, but no one was sure. Rohit would come to her college and would watch her through the window grilles until her father came to pick her up.

Rohit lost his father seven years ago in an accident and dropped out of school to take up odd jobs and support his mother and four sisters. Last month, when Maafi’s parents started looking for a man for her, she told them about Rohit.

But their love was doomed from the start. Rohit was from the Dhanak subcaste.

“In Haryana, within the Scheduled Castes, Chamars consider themselves superior to Dhanaks and Valmikis. They would not marry off their daughters or sons to the other sub-castes,” says Ranbir Singh former Dean (social science) Kurukshetra University. He calls it the Sanskritisation of sub-castes where hierarchy is closely linked to status.

“In Haryana, the Chamars are more educated. At the same time, the Dhanaks feel that they are superior to the Valmikis and would never let their daughters marry into the sub-caste,” he says.

Her parents were aghast, recalls one villager. “A Chamar marrying a Dhanak who doesn’t have any land to his name? Not possible,” he says.

Maafi was convinced that if Rohit got a good job her parents would change their minds. But it never happened and her parents were all the more determined to find her a good match.

“And that’s when they decided to elope,” says Maafi’s friend, who did not want to be named. She, Gitika and her other friends tried their best to stop her. “But she was too much in love,” she adds.

The day before her planned escape, she confided in Siya. She told her that she would be free after she married Rohit, and that he had even promised that she could continue studying.

A Chamar marrying a Dhanak who doesn’t have any land to his name? Not possible

– a villager

Maafi had packed a bag with a salwar kameez, her lipstick, and some artificial jewellery. Knowing that her parents would be away for the better part of the day, she skipped college on 14 September and offered to take care of the grocery store.

She was serving customers when Rohit arrived on a motorbike in the afternoon, says the granduncle.

As part of their investigation, police have pieced together what most likely happened based on eyewitness accounts and an informer.

According to the investigating officer, Rohit stopped at the grocery shop, and Maafi directed him to the adjoining narrow lane where her house was.

She met him there with her bag and got onto the seat. As Rohit kicked the bike into gear, her mother emerged from the house. She had reached home earlier than expected. She pulled Maafi’s dupatta from behind and dragged her back into the house. By then, Rohit had fled from the spot. The FIR however does not mention these details.

In Hisar, Rohit’s mother and sister are still waiting to hear from him. But the cops are convinced that he is hiding out of fear.

“There was no need to kill the daughter. The family should have informed us. We would have ensured that our boy stayed within his limits,” says Ajay Kumar, Rohit’s uncle.

Also Read: Inter-caste marriage isn’t the problem, marrying a Dalit man is

The police case

Maafi was cremated in no time. Her parents told everyone that their daughter died when the washing machine short-circuited. After the cremation, a quick panchayat meeting was convened where villagers decided to say that she died by suicide. But by then, the police had arrived based on a missing person’s report filed by the boyfriend’s family. He had told them of his plans.

The villagers have now shifted the blame to Maafi’s boyfriend, Rohit who is from Kherichopta village. This would not have happened if he hadn’t come to our village, says the council of men.

“There is no case against the boy. He is free. I am appalled. The police are not investigating properly,” says Kumar’s brother, Sube Singh.

The police suspect he is hiding out of fear of reprisal from Maafi’s family. His bike, which he abandoned after his plans failed, has been seized by the police.

When he did not return home as planned, his mother went to Kalayat police station in Kaithal district demanding answers. But by the time the police arrived at Balu village, Maafi had been cremated.

“Rohit’s mother was afraid for his life. After their complaint, I reached the village where the people had already conjured up a story of death by short circuit. But one of our sources in the village told us the real story of how the girl was killed,” says head constable, Suresh Kumar.

The police have registered a case against Kumar and his wife for murder (Section 302) and suppressing evidence of an offence committed (Section 201) among other sections of the Indian Penal Code. The FIR says that other members of the family were also involved, but so far only Kumar and Devi have been arrested.

“Such incidents still happen in Haryana, but they don’t even get reported because of the support of the sarpanch and villagers,” says a senior police officer from the Kalayat police station.

It’s very rare for couples who want to elope to seek protection from the police either.

It’s very rare for couples who want to elope to seek protection from the police either.

“The few who seek help are sent to protection houses, and an FIR is registered. But they can’t stay in the safe houses for long,” he adds.

‘Act of disobedience’

Back at Balu village, the informal durbar outside the grocery store is getting ready to disperse. It’s time to go home for dinner. The conversation has moved back to Maafi’s choices.

Her granduncle Kumar doesn’t understand how she could fall in love and jeopardise her when her parents had spent so much money on her college fees. He, too, has forgotten about the suicide theory.

“It was just that they were angry and choked her by mistake,” he says, sitting on the rickety chair with his arms crossed.

The men are more worried about who will look after the only son in the family, a five-year-old boy. Maafi’s two older sisters are married, and Siya enrolled in college this year. For now, she and her little brother are living with their uncle’s family.

It was just that they were angry and choked her by mistake

– Kumar, Maafi’s granduncle

“In the Ramayan, Ravan and his entire family were destroyed by Ram for Sita. The same tradition still continues. Had Sita been complicit the way our girl was, things would have been different. But Sita was not at fault,” says Krishan, the granduncle.

Reicha Tanwar is frustrated by the lack of control the women have over their personal lives. The ground-level situation has just not changed even after all these years.

“Haryana is close to Delhi but the modernity is cosmetic, superficial; it has not percolated within the society,” she says.

The young men in Balu village don’t want to talk about what happened. One 20-year-old boy is unhappy that Maafi’s “act of disobedience” has tarnished the image of the entire village. She should have married the man her parents chose, he says.

That’s what he plans to do.

“I don’t have a girlfriend, but I have five kilas of land. And it’s enough to get a wife,” he says.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)