New Delhi: A black-and-white photograph by Samsul Islam Almajee captures a gaunt mother cradling her child, her eyes hollow with hunger, devoid of any hope. In this intimate moment of stark vulnerability, the woman nurses her child. The image, taken in 1974 and recipient of an international award in 1975, has sparked debate for decades. If it was taken in 1974, it’s seen as evidence of the Bangladesh famine, if it’s 1975, it’s just regular hunger and poverty. This controversy, long outlasting the famine itself, mirrors the photograph’s enduring presence.

“It’s interesting why people insist on dating the photograph as 1975. Over the last 53 years, certain photographs have taken on new relevance, resurfacing each time a change in regime prompts a reevaluation of the past,” said Naeem Mohaiemen, a writer, researcher and associate professor of visual arts at Columbia University.

A pre-launch discussion of Naeem Mohaiemen’s upcoming book, Bengal Photography’s Reality Quest (Nokta, Dhaka), was held at the India International Centre on 3 January, in association with the Alkazi Foundation for the Arts. The event delved into the unresolved liberation struggles of the 1960s and 1970s in Bengal, exploring the complex interplay between memory and history. Mohaiemen, who researches this period, discussed the contradictory nature of social realism in photography, particularly in the two Bengals shaped by Partition.

The conversation featured Shukla Sawant and Suryanandini Narain from the School of Arts & Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University. Together, they examined the political tensions and ideological struggles that have shaped Bengal’s photographic identities, offering a thought-provoking preview of Mohaiemen’s book.

Also read: Is Chennai’s Margazhi Carnatic fest losing sheen? Empty halls, ageing fans, unpaid artists

The two Bengals

The Partition didn’t just redraw borders; it fractured cultural connections. In West Bengal, photography flourished as a dynamic art form, capturing everything from bustling streets to intimate moments, painting a rich picture of urban life. But in Bangladesh, the 1971 Liberation War became the heart of its photographic story. Amid the turmoil, the camera became a witness to the nation’s fight for freedom.

As Bangladesh rebuilt, social realism dominated its photography, driven by NGOs and international demand for stories of survival. The haunting images of famine, poverty, and refugee camps defined it on the global stage. But these powerful images often oversimplify the country’s journey, focusing on suffering and resilience, while neglecting its complexities.

“While both regions shared cultural ties before Partition, the political reality after 1947 shaped their photographic landscapes. West Bengal, as part of India, had more access to resources, opportunities, and networks,” said Mohaiemen. Kolkata has links with renowned photographers such as Pablo Bartholomew, Prabuddha Dasgupta, and Raghubir Singh. But for these photographers, Kolkata wasn’t the centre of their creative evolution, unlike their Bangladeshi counterparts, whose work was deeply rooted in their regional identity.

The path for Bangladeshi photographers was more constrained. After 1971, any significant career shift often meant relocating to North America or Europe. But true artistic expression could only be achieved in their homeland. Anwar Hussain moved to France but struggled to reconnect with Bangladesh’s art scene upon returning. In contrast, Shahidul Alam’s return was driven by a commitment to crafting a uniquely Bangladeshi narrative, one that transcended social realism and explored the nation’s identity.

The debate over these images, whether they document suffering or exploit it, continues to shape Bangladesh’s photographic identity. “While social realism gained global recognition, it also boxed the country’s photography into a narrow narrative. ‘Yet another award-winning image of poverty’ became a common critique locally, highlighting the discontent with what some saw as the commodification of suffering,” said Mohaiemen.

In contrast, West Bengal’s photography, though diverse, lacked a central identity. Photographers explored various themes, but the absence of a unifying narrative meant that West Bengal’s photography didn’t achieve the same level of global recognition as its neighbour.

During the Q&A, an audience member asked about the term ‘indigenous photography,’ which they found confusing. They questioned how technology could be considered indigenous, given that photography was not a native language for many communities at the time.

Mohaiemen explained that while photography was an imported technology, the term ‘indigenous’ invited a deeper look into how local influences shaped the art form. In Bangladesh, for instance, photographers often cited Western influences, even though local visual traditions, such as bazaar posters or peer influences, played a significant role. He emphasised the importance of recognising local practitioners who influenced the development of photography but were often overlooked in favour of Western references.

Also read: ‘Why do we take photos?’ Chennai’s 4th photo biennale is inspired by Dayanita Singh

The politics of memory

Sawant’s father, who, as a young boy, had joined the Indian Air Force and was trained in reconnaissance photography. His role during the war in Dhaka, witnessing devastation but keeping no war memorabilia or photographs, intrigued Sawant. “I wondered if his refusal to keep war mementoes was linked to the trauma he experienced,” she said. “The absence of photographs in my family home spoke volumes about how deeply the war affected those who lived through it.”

Mohaiemen shared his research on the misattribution of photographs and how key historical moments shape photographic narratives in both Bengals. He explained that for West Bengal, the Noakhali riots are crucial to understanding religious coexistence, while in Bangladesh, the 1971 war overshadows this. “For Bangladesh, the 1971 war erases the Noakhali riots. This erasure is not just political; it’s photographic,” he said.

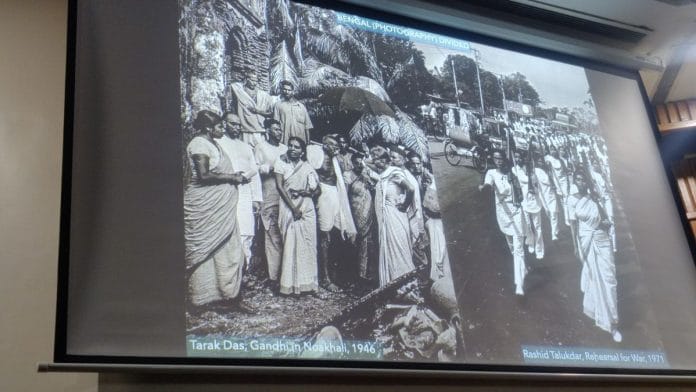

During his research, Mohaiemen encountered a person from Noakhali who questioned Gandhi’s visit to the area: “Why did Gandhi come here? Why didn’t he go to where Muslims were being slaughtered?” This moment highlighted the stark divide in how history is remembered and photographed by the two Bengals. Mohaiemen recalled how, for years, no one in Bangladesh had shown him the iconic Tarak Das photograph from the Noakhali riots. But when he found it in West Bengal, the response was, “How do you not know about this image?” This experience underscored the ongoing disconnect between the two regions.

This article has been updated to reflect factual changes.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)

Art, culture and science flourishes only in a society where people are provided with a secular education and therefore are open-minded. A society which encourages young ones to ask questions and think for themselves is the one which progresses in every domain of human endeavour.

Bangladesh, even post 1971, was dominated by the Islamic clergy. The Mullahs, in cahoots with the Army, called the shots. Naturally, the Bangladeshi education system simply does not equip a student with the required critical thinking skills. In fact, anyone asking questions about Islam and the questionable conduct of it’s Prophet and the Caliphs are subjected to “sar tan se juda” fatwas, violence, threats and intimidation. An example being Ms. Taslima Nasreen – currently residing in New Delhi.

How on earth can the arts flourish in such a society?