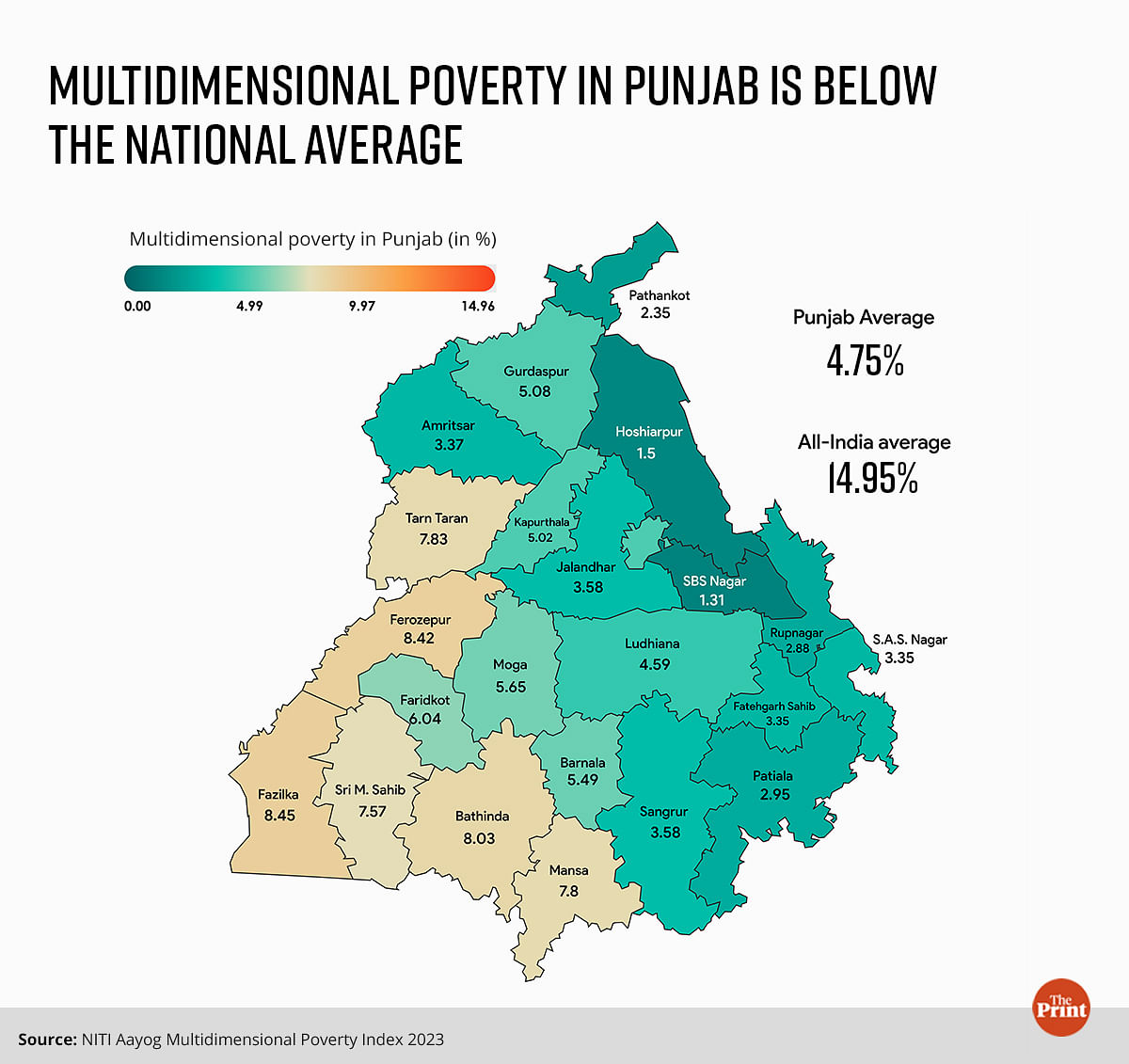

New Delhi: Less than 5 per cent of Punjab’s population was living in multidimensional poverty in 2021, according to the NITI Aayog’s Multidimensional Poverty Index 2023 released last week. To add to that, an analysis of the state government’s district-wise GDP data revealed that the state is witnessing low income disparity.

What does this mean? Simply put, while the percentage of those living in multidimensional poverty in the state is low, so is the percentage of those who can be classified in the high income group — which means that the bulk of Punjab’s population occupies a slim band somewhere in the middle.

Attributing low levels of multidimensional poverty in the state to the economic boom propelled by the Green Revolution in the 1960s and the infrastructure creation that followed, experts say this momentum is now waning due to Punjab’s overwhelming and continued dependence on agriculture.

This reflects in the numbers. Multidimensional poverty dipped for the state as a whole — from 5.57 per cent in 2016 to 4.75 per cent in 2021.

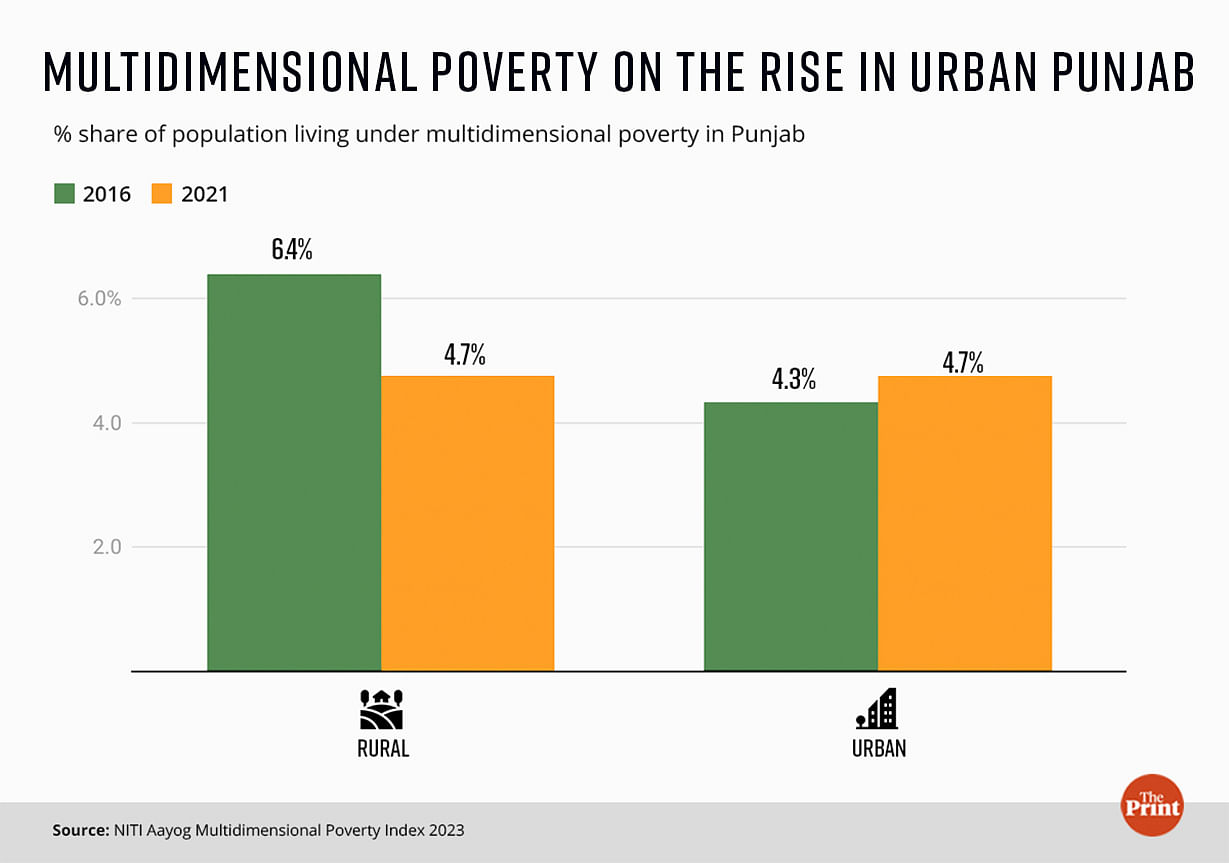

At the same time, NITI Aayog’s data shows that multidimensional poverty — which is based on deprivation of key health, education and standard of living indicators measured in the National Family Health Survey (NFHS) — rose marginally in urban Punjab during this period.

The proportion of those in urban Punjab living in multidimensional poverty increased to 4.76 per cent in 2021 from 4.32 per cent in 2016. This means that for every 1 lakh people living in urban Punjab in 2016, at least 4,320 were living in multidimensional poverty. By 2021, that number had risen to 4,760.

For instance, the share of people living in multidimensional poverty in Jalandhar surged by 0.33 percentage points between 2016 and 2021. Other urban districts witnessed a similar trend. Multidimensional poverty in Ludhiana rose by 0.75 percentage points, Rupnagar by 0.87 percentage points and Bathinda by a sharp 2.41 percentage points.

These indicators make Punjab the only Indian state with more than 10 million population reporting an increase in urban poverty.

According to Lakhwinder Gill, professor emeritus at the Punjabi University in Patiala, much of Punjab’s poverty reduction happened decades ago during the Green Revolution and its effects have since faded owing to little or no change in the structure of the state’s economy.

“The Green Revolution was a major game changer in Punjab,” Gill explained. “Various scholars have concluded that not only did it increase the incomes of people living in Punjab, the government also gained and spent money on building state of the art road networks, building primary healthcare centres across rural Punjab etc.”

“So, today’s low level of multidimensional poverty in Punjab is a result of the efforts placed nearly three-four decades ago,” he said to ThePrint.

Lack of structural change

But why is poverty alleviation going in reverse gear in Punjab’s richer, more urban districts? The answer lies in the structural transition of the state (or the lack thereof), characterised by the paucity of land that curtails the state’s ability to generate more income from agriculture.

A detailed ground report by ThePrint in 2022 had revealed how despite agro processing industries adding to its output, Punjab did not become a flourishing ground for industries.

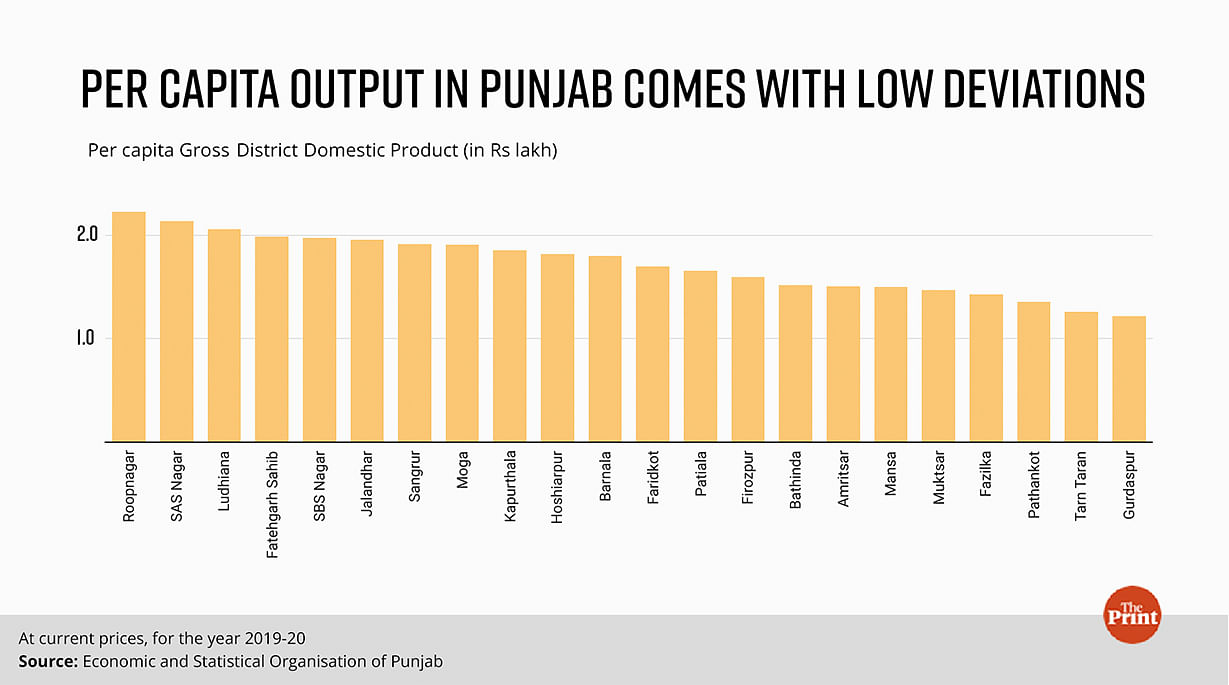

This may explain the high level of income parity across districts.

ThePrint’s calculation of the district-wise per capita GDP data shows that inequality in the state — as shown in a technical measure called the Gini coefficient — was about 0.11 in 2019-20. A Gini coefficient of 0 denotes perfect equality and 1 denotes complete inequality.

This means that people in Punjab are likely to have about the same levels of income irrespective of where they live since there are no metros like Delhi, Mumbai, Bengaluru or Gurugram to raise their chances of earning higher incomes.

Gill believed that the lack of the state’s ability to steer its economy from agriculture to industries or high-valued services led to a reversal in poverty indicators in areas less dependent on agriculture for incomes.

“The state’s inability to generate income beyond agriculture is exactly the reason why I feel there is a reversal of poverty in Punjab,” he argued.

Gill added, “The three sectors (agri-industry-services) are not interlinked with each other. The gap between the rich and the poor is widening and on top of that, the mechanisation of agriculture has also forfeited the possibility of jobs that the poor could have done to earn money.”

His assertions are backed by data available with the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation which shows that the composition of Punjab’s economic output has remained almost unchanged in the past decade.

In 2011-12, the secondary sector, which includes manufacturing, construction and production of other utilities like electricity, gas and water supply, contributed 25.4 per cent to the state’s overall output, which declined marginally to 25.15 per cent by 2022-23.

The growth in Punjab’s industrial sector has averaged 4.7 per cent in the past decade (2012-13 to 2022-23) against the national average of 5.7 per cent.

At the same time, the agricultural sector, which contributes 30 per cent of the state’s income, has grown by just 2.2 per cent against the national average of 3.9 per cent. The services sector has grown by 5.7 per cent during this period, which is also slower than the national average of 6.4 per cent.

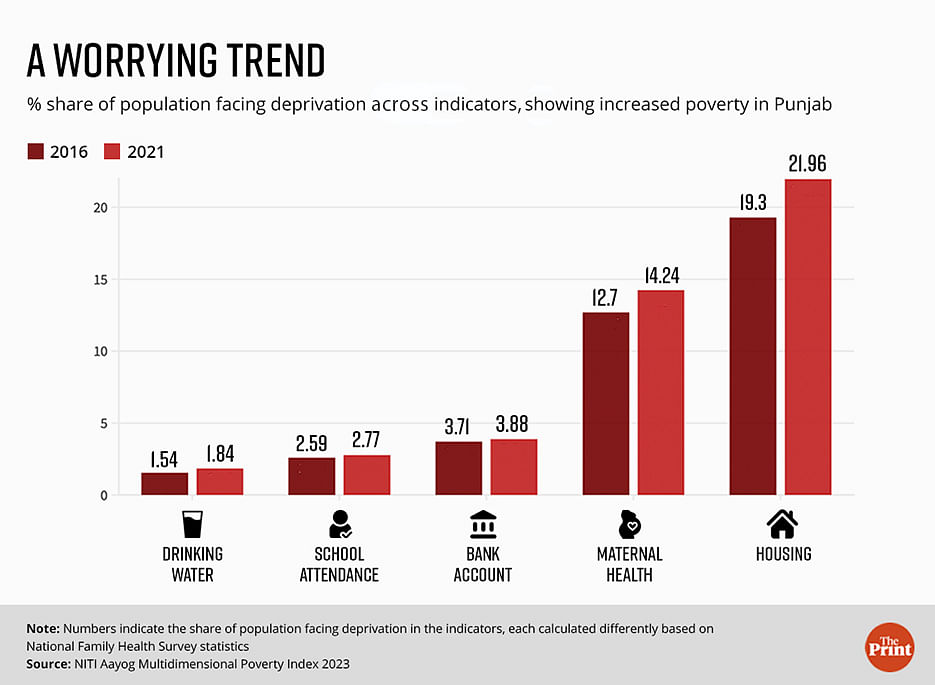

A closer look also reveals that Punjab witnessed a slight uptick in deprivation on five of the 12 sub-indicators listed in the NITI Aayog’s Multidimensional Poverty Index.

Deprivation in housing — share of people who live in a house in which “the floor is made of natural materials, or the roof or wall are made of rudimentary materials” — jumped from 19.3 per cent in 2016 to 22 per cent in 2021.

Similarly, the share of women deprived of maternal health (those who did not receive at least four antenatal care visits for the most recent birth or did not receive medical assistance during the most recent childbirth) rose from 12.7 per cent to 14.24 per cent.

Further, deprivation in the state in terms of bank account, school attendance and drinking water (see graphic), too, witnessed an increase during the same period.

“Either the state does another Green Revolution or fixes its industrial and services sectors, that only can deter poverty from rising,” Gill concluded.

However, NITI Aayog’s Multidimensional Poverty Index data alone doesn’t define who is at the bottom of the pyramid, said professor Upinder Sawhney of Panjab University’s department of economics. “Punjab’s poverty numbers need a deeper scrutiny,” he said.

“It has attracted physical labour from less developed states for generations, but from the Multidimensional Poverty Index data, we don’t know who is affected by the rise in multidimensional poverty. One needs to assess whether poverty is affecting those who migrated to Punjab or if it is also affecting the entire state before arriving at conclusions.”

(Edited by Amrtansh Arora)

Also Read: Why India’s non-Basmati rice export ban could hit global markets hard