Like history in India today — disputed, contradicted, excavated — former Archaeological Survey of India head Braj Basi Lal’s legacy is torn between those exulting him as a “great intellectual” who connected India with its rich past and others criticising him for the “abuse of archaeology”.

And like chapters in history that ruffle feathers from time to time, B.B. Lal is a name that will continue to excite, rouse, inspire — and even anger — people.

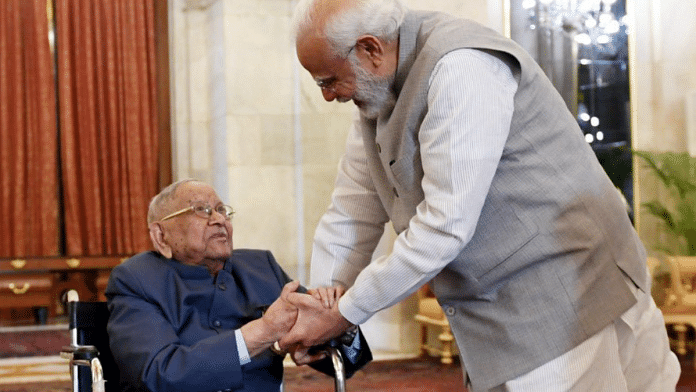

When Lal passed away on 10 September at the age of 101, political leaders from Prime Minister Narendra Modi to Union Culture Minister G. Kishan Reddy and the ASI paid rich tributes to the Padma Vibhushan awardee.

A few decades earlier, two eminent British archaeologists had called Lal’s work “models of research and excavation reporting” in the Journal of the Archaeological Survey of India.

Rising prominence

B.B. Lal’s critics, though, were as disparaging as those who lauded his work. In the Babri Masjid demolition controversy, Lal’s 1990 article in the Bharatiya Janata Party-affiliated magazine Manthan was the “original lie”, said cultural anthropologist Ashish Avikunthak. The archaeologist had led the excavation of the site in the mid-1970s, having found no trace of any Hindu temple. “He did not show any interest in determining the birthplace of Lord Ram in Ayodhya in the 1970s,” wrote history scholar Hilal Ahmed. But one morning 10 years later, he turned the narrative around: People were suddenly told that there were indeed temple pillar bases at the site.

Born on 2 May 1921 in Jhansi, Uttar Pradesh, B.B. Lal grew up with a passion for ancient Indian history and Hindu epics. He sustained it through Independent India’s founding decade. He graduated with a master’s degree in Sanskrit from Allahabad University and trained under then-ASI head Mortimer Wheeler at Taxila, Punjab, and Harappan sites in the 1940s.

Lal chose the threads of Indian history he wanted to pluck — the Indus Valley and the excavation sites associated with the Hindu epics Ramayana and Mahabharata. His pioneering work across the North Indian River Plain and Nubia, Africa, in excavating Middle and Late Stone Age tools led to his rising prominence in the ASI. In 1968, he replaced Amalananda Ghosh as its director-general.

His confidence in uncovering a nexus between Hindu epics, archaeology and Indian history only grew stronger.

Lal condensed decades of his work on Mahabharata-related excavations in a 1975 paper titled In Search of India’s Traditional Past in India International Centre Quarterly. Although “inflated during the course of time”, the evidence for the Hindu myth exists, he then argued. The same year, he started the ASI-funded ‘Archaeology of the Ramayana Sites’ project in five regions traditionally believed to be associated with the epic — Ayodhya, Bharadwaj Ashram, Nandigram, Chitrakoot and Sringaverapura. It was no surprise which site would become a live wire in the Indian political arena a decade later. And that started B.B. Lal’s political wrangling.

Despite his legacy, Lal’s loyalists have had to bite their tongue all too often— ‘archaeological jingoism’, ‘systematic abuse’, ‘irrational’, ‘communal’, and ‘manufactured’ are the most impassioned charges coming from his critics. And it all had a supposedly innocuous beginning.

Also read: Bhikaji Cama—Parsi revolutionary who plotted Savarkar’s escape, raised 1st Indian flag abroad

Pillars and motifs

In the 1977 ASI report, following the 1975 Ramayana sites project, Lal found that Ayodhya excavations were “devoid of any interest”. In 1989, the ‘facts’ became passing suggestions of ‘pillar bases’; a year later, with absolute surety, “remains of a columned temple”, and then in 2008, “twelve pillars with not only typical Hindu motifs and mouldings but also figures of Hindu deities”. Lal’s work was not published in any professional academic journal.

Meanwhile, two events unfolded that would not be forgotten easily.

One, at the third World Archaeological Congress (WAC) in New Delhi in 1994, political daggers were pulled out when senior archaeologists led by Lal turned physical onstage, preventing opposing members from reading out a petition against the Babri Masjid demolition. Two, Lal spurned National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) history author R.S. Sharma in 2002 by countering the emigrant Aryan theory and claiming that the tribe was indigenous to India in his book The Saraswati Flows On.

But amid all the mud-slinging, B.B. Lal held up the defence of a classic historian: “The climate of the time would suggest that I’m saffronising history. That is a great tragedy. I only ask everyone to look at the facts.”

(Edited by Ratan Priya)