It’s been three years since Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. US President Donald Trump has begun peace talks with Russia, excluding Ukraine and Europe out of the process, and saying that Russia has “the cards” to end the war as it has taken a lot of territory. Trump’s conduct has sparked frustration and fear in Europe, with many doubting his commitment to the transatlantic alliance. In this episode of ThePrint Explorer, Praveen Swami looks at the revival of the idea of a European military architecture to defend the continent.

New Delhi: Twelve full months had passed since the end of the Second World War, when Winston Churchill rose to deliver his reflections on the legacy of that titanic epoch-shaping struggle. Across Europe, he said at Zurich University, there were “a vast, quivering mass of tormented, hungry, careworn and bewildered human beings, who wait in the ruins of their cities and homes and scan the dark horizons for the approach of some new form of tyranny or terror”.

“Among the victors, there is a Babel of voices, among the vanquished the sullen silence of despair.”

Even though Churchill is now often seen as an island-bound English nationalist, that speech saw him lay out a far wider vision. Europe, he said, was “the home of all the great parent races of the Western world, the foundation of Christian faith and ethics, the origin of most of the culture, arts, philosophy and science, both of ancient and modern times”.

To recreate this great Europe, Churchill went on, there “must be a partnership between France and Germany”. And then, he concluded, “we must build a kind of United States of Europe”.

We live in times when the United Kingdom was led out of the European Union by leaders like former Prime Minister Boris Johnson and Nigel Farage, who claim to venerate Churchill. Farage sees American President Donald Trump as the new Churchill, and Johnson actually wrote a book about him. Make what you will of this.

Anyway, my main point is this: in 1950, as war broke out in the Koreas, Churchill sought to push a resolution through the newly-created Council of Europe, asking for “the immediate creation of a unified European Army, subject to proper European democratic control and acting in full co-operation with the United States and Canada”. The Council declined, saying it didn’t have the power.

That was Churchill who called for a European army, not some dyed-in-pink, pot-smoking liberal. Again, make of it what you will, but that’s what happened.

Hello and thank you again for joining this week’s episode of ThePrint Explorer, where we’re going to be discussing new calls now being made for a European military. I thought about calling this episode “Can goldfish bite”, along the lines of “Can pigs fly”, but that would have been rude, and I don’t want to be rude. And, honestly, for all I know, goldfish could have a really nasty bite.

Also Read: How an American corporate corruption scandal in 1974 laid the foundations for Adani US indictment

Russia-Ukraine war

Europe has been set on fire this week by President Donald Trump, who seemed to revoke decades of American security guarantees to Europe. As the historian of contemporary Europe, Timothy Garton Ash writes, Trump has shown he “not only bullies his country’s friends but sucks up to his country’s enemies”.

Trump has suggested Russia can keep the Ukrainian territory it has captured. He’s excluded Ukraine from ongoing talks with Russia. And according to the Daily Telegraph, he’s demanded half of Ukraine’s $11.5 billion reserves of rare earth minerals in return for US military assistance.

Where the $500 billion figure comes from, I cannot tell you, because the United States officially says it’s given $69.2 billion to Ukraine since 2014. Even my credit card company doesn’t charge that kind of interest.

Anyway, all this has set off an unprecedented wave of fear in European capitals. Keir Starmer, the British prime minister, has said he’s willing to put troops on the ground to enforce a peace deal along the Ukrainian-Russian border. France has said it’s not yet willing to send combat troops to the frontline, but has also said it wants Ukraine to get automatic membership of NATO in the event of Russian violation of a future ceasefire. That would mean, presumably, that it is ready to commit French troops, since an attack on one NATO member is deemed an attack on all members.

European Union leaders are also bringing $6.2 billion to the table to sustain Ukraine’s defence forces, which will compensate in part for the loss of US aid, but it’s far from clear if they have the industrial base to deliver the material the country needs.

Last year, the International Institute of Strategic Studies noted that while the EU produced some exquisite high-technology weaponry, its production rates for bread-and-butter items, like tanks, artillery and anti-submarine warfare aircraft were just too low.

There are plans in place to change all this, but factories don’t get built from paper. The EU has estimated that to build a credible deterrent, its members need to spend $500 billion over the next ten years. Voters battered by inflation and declining social services may not be thrilled by the idea.

France has just hosted a European summit on these issues, and one of the ideas that has been rattling around the corridors of power is that there should be a European military to defend European interests, even if the United States is no longer willing to guarantee the continent’s security. Former Estonian foreign minister Urmas Paet, for example, has called for a kind of military Schengen zone, where countries cede their defence responsibility to a common executive agency or council.

Everyone, of course, doesn’t agree. Kaja Kallas, the EU’s foreign policy head, says it needs 27 functioning militaries—one for each of its members—not one, which is another way of saying the status quo, with American leadership of NATO, can alone guarantee the continent’s defence.

All, of course, know what the bottom line is. Browen Maddox, the Director of Chatham House, writes that Trump “has fundamentally undermined European confidence in US commitment to NATO and the principle of mutual defence”.

“To hold the line, France, the UK and Poland will all have to send troops into Ukraine, and hope the US continues to supply missiles and aircraft. They’ll have to find enormous amounts of cash.”

This is much easier said than done. In 2021, the expert David Axe reported that the United Kingdom would struggle to deploy a single brigade in a sustained conventional warfare role because of equipment shortages. The 3 Division of the British Army is the only UK force maintained continually at a state of war-readiness, and credible testimony in 2020 suggested it could not defeat a peer-adversary like Russia. This was, among other things, because of problems in its armoured vehicle capabilities.

France has done somewhat better, a 2021 study by Stephanie Pezard and her colleagues concluded. The country has the resources to support the United States in a high-intensity war in Europe, but lacks the depth necessary to sustain a war over a long period. The German Heer, or land forces, for their part, are tiny, with the capability to deploy a combat force of just 10,000 soldiers, only 4,000 of whom can be sustained over a long period.

The idea of a European military

To understand how Europe got here, it’s important to go back to that 1950 meeting, where Churchill first made his proposals for a European military. There was no consensus, and given the hideous experience of two wars begun by Germany, there probably couldn’t have been. French leader André Philip said he understood the danger to Europe from the Soviet Union, but saw it as less dangerous than reconstituting the German military. Leaders from the UK, for their part, argued there could be no defence against Soviet power without Germany.

Late in 1950, French prime minister René Pleven submitted a proposal inspired by Churchill, calling for a European assembly with a European minister of defence responsible to it and carrying out the directions of a council of ministers representing all the member-states.

In 1952, the Pleven Plan graduated into a treaty, which envisaged a 43-division force being created. France would have contributed 14 divisions and 750 aircraft, Italy 12 divisions and 450 aircraft, the Benelux countries five divisions and 600 aircraft, and West Germany 12 divisions but no combat aircraft, which the rest of Europe, at that stage, did not want to give them.

This military would need political leadership, of course, and that was to come from an institution called the European Political Community. France, however, refused to ratify the creation of the European Political Community in 1954, seeing it as an unacceptable dilution of national sovereignty. That pretty much killed the idea of a European military.

Further problems erupted in 1956, when France and the United Kingdom joined Israel in attacking the Suez Canal after Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser nationalised the British and French-owned Suez Canal Company.

The United States was less than delighted by this Anglo-French operation. The French were also less than pleased that NATO would not join it in defending its colonial territories in Algeria, unlike in Indochina—or what is today Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia. The fact was, however, that the Europeans just could not agree on a way to defend themselves.

Thus, NATO, with America as its keystone, became pretty much the central institution of European defence. The arrangement was tested in 1958, when Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev gave a speech demanding that the Western powers—the United States, great Britain and France—pull their forces out of West Berlin within six months. West Berlin was nestled deep inside East German territory and a Soviet blockade would have cut it off from West Germany altogether.

Earlier, in 1948, the Soviet Union had sparked a crisis in the city by cutting off land access between West Germany and West Berlin, necessitating a year-long airlift of supplies. The Soviets argued, correctly, that after the war, the four powers had promised to reunify the city. The Western powers, however, argued that conditions were not right for that. The crisis was defused though, and both sides edged away from war.

Khruschev’s 1958 threat, though, seemed set to have a less happy outcome. There were tensions over East Asia, as well as American U2 spy flights over the Soviet Union. In response to Khruschev’s demands, President John F. Kennedy mobilised military reserves and increased defence expenditure, signalling willingness to go to war over Berlin.

The Soviet Union responded by stringing a barbed wire fence across the city, which would later become the Berlin Wall. There were several tense moments before secret diplomacy helped both sides back away.

From declassified diplomatic documents, we now know some leaders in the United States and Europe saw things in very different ways.

French president Charles de Gaulle came away from the Berlin crisis convinced that his nation needed autonomy of action and the ability to defend itself. The two great powers, he believed, would be willing to sacrifice the interests of countries like France to insulate themselves from the horrific consequences of a nuclear war. Historian Toshihiko Aono has observed that London and Washington also repeatedly disagreed on the handling of the Berlin crisis.

Later, in 1966, as a consequence of these agreements and suspicions, France left NATO’s integrated military command, though it remained a member of the organisation. French staff today participate in NATO’s military committee, its central decision-making body, but its troops are not under the multinational alliance’s command.

To understand the full implications of this European-American tension, we have to take a little detour into the very ugly world of nuclear weapons.

Also Read: Exile of atheist poet Daud Haider shows Bangladesh wasn’t secular paradise even 50 years ago

The nuclear factor

Embedded in the rock more than 25 metres below the snow-dusted heart of Stockholm, the cavern is now an empty hall, sometimes hired out for concerts and exhibitions.

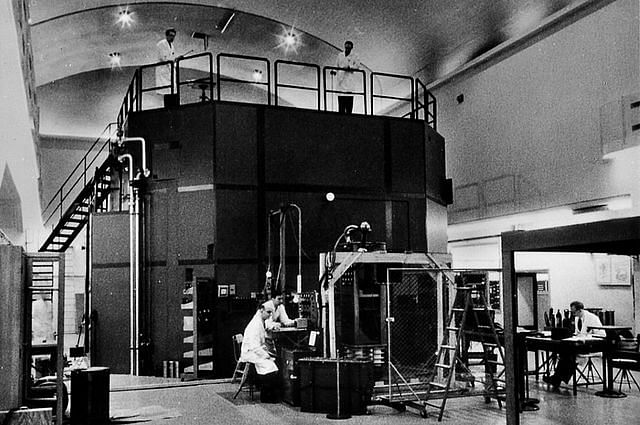

Seven decades ago this summer, the hall became home to a nuclear reactor that silently produced weapons-grade plutonium, the heart of one the world’s most secret nuclear weapons programmes. After Hiroshima, military experts had warned that the new kind of bomb dropped on the city would transform warfare. Workers’ shovels soon began hitting frozen earth.

The hall wasn’t under one of the Soviet Union’s secret nuclear cities—which began being constructed after dictator Joseph Stalin’s atomic spies informed him of the Manhattan Project—or in the wastes of China’s Lop Nur. It wasn’t under the Fontenay-aux-Roses in Paris, where France had begun to breed plutonium, or run by the discreetly named Tube Alloys, the British nuclear weapons programme.

Largely forgotten today, the story of R1 nuclear reactor in Stockholm—the capital of social-democratic free-love-and-sandals Sweden—helps us understand the security dilemmas facing Europe after Second World War.

Would, as General De Gaulle put it, America really be willing to sacrifice New York for Paris? And what would happen if Germany became powerful again, and attacked France once again? These questions haunted European leaders in the wake of the Second World War, for all the warm talk about shared democratic values and civilisation.

Efforts like the Swedish nuclear programme had begun across Europe. The United Kingdom had made major contributions to kickstarting the American Manhattan Project. Leaders in the UK, official history records show, expected that the US would return the favour by sharing technology after the end of the Second World War. Fearing the technology would leak to the USSR, however, American President Harry Truman declined to cooperate.

Furious, British politicians ordered resources made available for the acquisition of an independent nuclear deterrent in 1946. “We’ve got to have this thing over here, whatever it costs,” Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin told the cabinet committee in charge of the project. “We’ve got to have the bloody Union Jack flying on top of it.”

Across the English Channel, France was arriving at the same conclusion, and for pretty much the same reason. The French government had acquired much of the world’s heavy water supply in 1940 and moved it to the UK. Physicists Lew Kowarski and Hans von Halban later conducted experiments that proved fission—and thus nuclear weapons—was possible.

Later, in 1944, the French scientist Jules Guéron, one of the three involved in the Manhattan Project, gave leader-in-exile Charles de Gaulle a one-on-one secret briefing on the new weapons, nuclear policy expert Mycle Schneider records. Even today, French nuclear forces remain outside NATO’s structure. It’s the ultimate deterrent.

Trump’s threats, as his former national security adviser John Bolton has noted, is starting to push American allies across the world to begin wondering how credible the superpower’s security guarantees really are. “Well”, Bolton observed, “if Trump is willing to knife NATO, what makes anybody think he wouldn’t knife Israel if it suited his purposes?”

Look at European political parties, and you’ll see lots of support for a European military architecture. French president Macron has backed the idea, and so did former German chancellor Angela Merkel. Almost all major German political parties had a reference to a European army in their election manifestos for the last federal election.

Challenges to creating a European army

For all the big talk about a European military, there are significant practical problems standing in the way of actually creating one.

“Europeans”, scholar Ulrike Franke notes, “have 17 different types of battle tanks—each emerging from a national industrial base—while the United States has one. Where the USA has six important types of combat aircraft, Europe has 20. And even though the EU states combined have around 1.3 million soldiers under their command, every time there is need to deploy forces, Europeans struggle to send and equip even small numbers of soldiers. In the EU, there are 27 armed forces, 27 procurement authorities and 27 defence industrial markets.”

The Europeans recognise this and we have seen some incremental progress towards creating an autonomous military capability.

They already have battlegroups, which have theoretically been operational since 2007. They bring together several thousand soldiers who are supposed to be operational within 10 days of being given a command. They are provided by EU states on a rotational basis.

However, to this day, they have never been deployed, because EU member states could not agree on the circumstances in which to do so. The 2022 EU’s “Strategic Compass” also proposes the establishment of “an EU Rapid Deployment Capacity” of up to 5,000 troops. Five thousand troops, though, are a tiny number.

Then, there’s that eternal problem Trump never ceases to point out—ten European NATO countries currently reach the target of 2 percent of gross domestic product for defence—which they committed to decades ago—while 18 do not.

The UK is committed to reaching 2.5 percent of GDP for defence, but is shooting down all calls to raise that to three percent despite the deficits and the situation in Ukraine. Likely, Prime Minister Starmer believes—and in my opinion, correctly—that his voters mostly don’t think the threat from Russia is large enough to justify social security and healthcare cuts.

The European Union does have a defence clause, which was invoked for the first time in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks against France in November 2015. That action was, however, symbolic, which is probably why it could be taken. Ask European states to prepare for a long war against Russia, and there’ll probably be some embarrassed shuffling around the room.

Like in the United States, there are serious debates in Europe over just what price is worth paying to contain Russia. Is it worth making concessions to Moscow in the interests of containing China? Or is that a chimera, which will only feed President Vladimir Putin’s ambitions? These are complex questions and there’s no easy answer.

The problem goes far deeper, moreover, than mere calculations of geopolitics and collective security. The transatlantic order was founded on lived memories of two world wars, where the United States had to intervene to save Europe from itself.

There were plenty of people in the United States, even in the build-up to the Second World War, either with Nazi sympathies or who believed their country ought to leave Europe to its fate, no matter the consequences. It’s worth remembering that Trump’s slogan “America First” was actually invented in the build-up to the Second World War by Charles Lindbergh, the legendary aviator who was a leading proponent of staying out of Europe.

As memories of those two savage wars fade, so is understanding of the toxic nationalisms and racism which drove Europe to war, as well as a cognisance of what the price of misjudging geopolitics in an interconnected world can be.

Europeans are trying to insulate themselves and create a backbone to protect the alliance they’ve built. They are very far, however, from actually having the muscle to protect themselves and Trump’s made clear that time is not on their side.

(Edited by Mannat Chugh)

Also Read: Why China accessing East Sea through Russia-North Korea border river can ring alarm bells