While UPA resorted to big-bang rural policies, the approach of NDA-2 has been subtle and focused on completing programmes of its predecessor as the BJP tries to shed the image of being a party of the urban classes.

Having completed three years in power and its eyes firmly set on winning a second term in 2019, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s BJP government would be hoping to secure the backing of not just its traditional constituencies but also targeting a new one – the rural voter.

The BJP obviously does not want to repeat its mistake of 2004 when it lost due to a perception of being a government for the urban, well-off sections. Having learnt its lesson, a ‘Gaon, Gareeb, Kisan’ (village, poor, farmer) focus was stressed by this government. However, the Modi government’s approach to rural policy is decidedly distinct from that of its predecessor – the Congress-led UPA government, which carefully crafted an image of a pro-poor, pro-welfare and pro-rural dispensation.

The UPA government had a more big-bang approach to its rural policies and its desire to leave behind a legacy through legislation and policy initiatives was very obvious. The marquee Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Act came in February 2006, less than two years after the alliance came to power. MGNREGA has widely been credited as being one of the main factors that won the UPA a second term in 2009.

In the second term, the UPA’s big pro-farmer initiative was The Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition Act, which although much criticised for being impractical and anti-industry, had the perception of being a legislation that was fiercely protecting the rights of the poor farmer.

So politically and electorally crucial were these two legislations that despite the negative disposition against them, the BJP-led government could do little to reverse these initiatives or even dilute them after coming to power. MGNREGA was publicly trashed by PM Modi and by then rural development minister Nitin Gadkari. In its first year, the government was accused of trying to slowly kill the scheme by creating a funds crunch and dampening planning. Similarly, the government invested much social and political capital to water down the Land Acquisition Act, even promulgating ordinances in the process. However, political and electoral compulsions ensured the government eventually gave due importance to both the legislations and backed off from its efforts to diminish them.

Another rural initiative by UPA – the Prime Minister’s Rural Development Fellows – has been put on the backburner by this government, despite PM Modi himself throwing his weight behind it early last year.

To be sure, the UPA’s implementation of its own rural schemes was questionable and at best, patchy. MGNREGA was plagued by corruption and loopholes, which this government has attempted to correct to a great extent. The UPA also abandoned its own initiatives like Socio Economic Caste Census or SECC and Direct Benefits Transfer (DBT) midway, which again the Modi government has taken to a logical conclusion.

The initial hiccups notwithstanding, the Modi government has ensured a more balanced rural focus. Unlike its predecessor, it has no big initiative, no headline grabbing legislation and no massive funds allocation to a rural scheme to show just yet. Its approach has been more subtle, and based on completing and strengthening initiatives of the UPA.

The SECC conducted by the previous government was brought to its logical conclusion by the BJP government, which now uses it as the basis of determining beneficiaries of all key schemes under the Rural Development Ministry. DBT, another initiative of the previous dispensation, has been taken forward by the Modi government. With a push to Aadhaar enrollment and seeding, DBT is being used to transfer money directly and seamlessly to the accounts of beneficiaries of various schemes. In MGNREGA, geo-tagging of assets has been a huge initiative to keep track of assets being created and to minimise corruption.

Jan Dhan Yojana, the free LPG scheme, and Housing for All have strong rural undercurrents, even though they are not just targeted at rural India. However, what cannot be denied is that this government does not have that one spectacular scheme or unique selling point for its rural voters, unlike the UPA government did given it is merely consolidating existing programmes instead of launching a big rural initiative of its own. Besides, there have been some damp squibs as well.

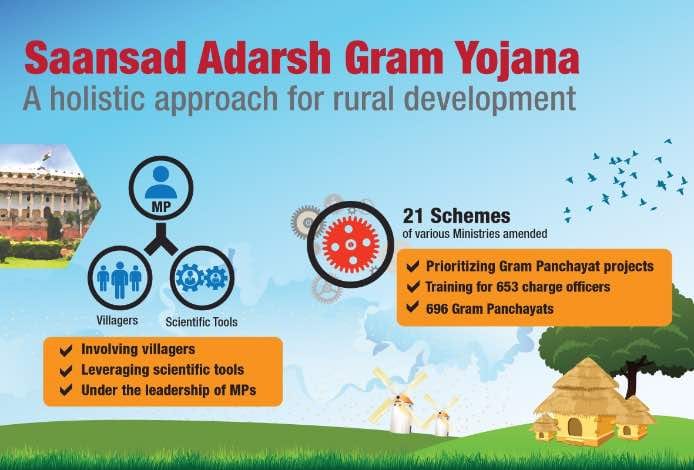

The PM’s Sansad Adarsh Gram Yojana, launched with much fanfare, has seen little, if no result. The programme required each MP to take the responsibility of adopting and developing three villages in her/his constituency by 2019. However, with no extra funds allotted for this programme and no concrete structure, this has remained mere lip service than an actual, on-ground scheme. The government’s reworking and renaming of Indira Awas Yojana has barely added any new dimensions to the scheme. In skill development, another pet area for this government, precious little has been done for rural India besides re-christening older schemes like the National Rural Livelihoods Mission and giving them a make-over.

The Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana (PMGSY) – a contribution of the NDA government under former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee – has been given some push but road connectivity continues to remain a hurdle in difficult terrains as well as conflict zones like Maoist-affected areas.

The Vajpayee government left behind PMGSY as its rural legacy, the UPA had MGNREGA and to some extent, the Land Acquisition Act. Will the BJP government under PM Modi be content with merely carrying forward the legacy of its predecessors, or will it throw a surprise with a game-changing rural programme? Either way, Modi Sarkar has shed the image of BJP being a party of the urban well-off by underscoring the importance of government initiatives for rural India, even if done subtly and with varying degrees of success.