The stench overwhelmed the socialist sensibilities of Indian nationalism’s English Aunty-ji: “They are essentially an unclean race,” the scholar and activist Beatrice Webb confided in her diary, as she travelled through late imperial China in 1911. Following visits to the homes of male sex workers, she lamented the country’s “rottenness of physical and moral character”. The “vicious femininity” of men’s faces, it seemed to her, provided evidence of widespread sodomy. “Their constitution seems devastated by drugs and abnormal sexual indulgence,” Webb raged. “A horrid race.”

Later, historian Tom Buchanan records that philosopher Bertrand Russell explained why Webb—a pacifist, and passionate advocate of Home Rule for India—fell in love with a militarist, empire-worshipping Japan: “There were no lavatories at the railway stations in China.”

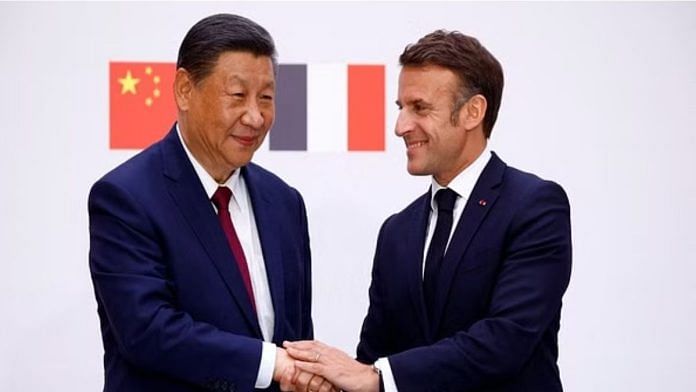

This week, Xi Jinping—leader of a new China with state-of-the-art railway stations, sparkling-clean toilets, and police who are stamping out homosexuality—is in France, hoping to convince increasingly sceptical Europeans of the value of their relationship. Eighty years ago, France established diplomatic relations with Beijing, a decade and a half before Former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger’s famous secret diplomacy opened the West’s doors to the People’s Republic of China. Xi is hoping France will again open its doors.

Like many other countries in Asia, India is watching anxiously, concerned that its most important strategic partner in Europe isn’t seduced. France’s President Emmanuel Macron has been telling Xi that he expects China to end its economic and military support for Russia. Xi has responded testily, saying China is “not at the origin of this crisis, nor a party to it, nor a participant.”

This tension is good news for India—except that New Delhi is also drawing criticism for helping to underwrite the war. Europe, moreover, is deeply divided on confronting China. The German chancellor Olaf Scholz seemed unwilling to press the superpower either on trade disputes or geopolitics last month. There is an urgent need to engage European capitals more energetically if the debate is to tip India’s way.

Also read: Two documents, Modi-Macron visits—India-France defence partnership is touching new heights

France’s pursuit of autonomy

Early in 1964, as China-backed North Vietnam defeated the South in a series of battles and the US prepared to step up its military involvement, then French president Charles de Gaulle offered information Minister Alain Peyrefitte this prescient analysis: “China’s means are enormous. It is not excluded that in the next century [it] will become once again the dominant global power.” French recognition of the People’s Republic of China, he argued, would “move an enormous rock with a simple lever”.

European powers on either side of the Iron Curtain, historian Vojtech Mastny has recorded, were alarmed by the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. They realised how close they had come to a nuclear war between the superpowers with no influence over their course or direction.

Even though it supported the Soviet Union as the crisis developed, scholar Enrico Maria Fardella writes that Beijing publicly accused Moscow of “adventurism” for having placed the missiles in Cuba and “capitulationism” for agreeing to pull them out in the face of an American ultimatum.

France, historian Garret Martin explains, drew two important lessons from the 1962 missile crisis. First, neither superpower wanted war—which opened up the possibility of an independent peace with Moscow. The second lesson was that the US would not risk nuclear war to defend Europe, which made it important for France to deepen its strategic autonomy, and independent nuclear deterrent capabilities.

To De Gaulle, Garret notes, the nation—rather than ideological bloc—was reemerging as the central element in geopolitics. Thus, China and India were at war, unrelated to superpower bloc politics, De Gaulle told a cabinet meeting in November 1962. China and the Soviet Union were also locked in conflict. France became increasingly committed to pursuing an independent strategic policy.

In 1963, France rejected offers of Polaris missiles from the US in return for joining a multilateral force of nuclear-armed submarines and warships, which would be crewed by North Atlantic Treaty Organisation troops. Even though De Gaulle’s hopes of building an alternate French-German strategic alliance were thwarted, he had another card up his sleeve to grow French strategic autonomy.

Also read: India must kill terrorists. Nijjar blowback shows it also needs laws to guide assassins

Talking to Beijing

Edgar Faure—essayist, historian, and former French prime minister—arrived in Beijing in the winter of 1963, armed with a sealed letter from De Gaulle. Later, in a letter despatched by a diplomatic courier from New Delhi, he told De Gaulle that France was seen as a potential supporter of China among non-socialist powers. Zhou Enlai, the former premier of the People’s Republic of China, and foreign minister Chen Yi spent an entire evening briefing Faure justifying the war with India, which had irked both the US and the Soviet Union.

The meeting ended with an agreement on resuming diplomatic relations, and recognition of the claims of the People’s Republic of China to a seat at the United Nations. Less than a year later, France would make its recognition public, stunning the US.

In fact, France was not the first Western power to engage China: The Labour government in the UK granted it recognition in 1950, following Norway, Denmark Finland, and Sweden. The UK hoped to protect its trade interests in China, as well as its position in Hong Kong. However, feuds over the UK’s relationship with Taiwan obstructed a full diplomatic relationship and the outbreak of the war in Korea sabotaged further progress.

Labour politicians made brave efforts to sustain dialogues with China. Member of Parliament Barbara Castle, Buchanan writes, visited a cooperative farm: “I was taken into a shed full of pigs and hay and given a pot! The women stood around while I had my pee!” Efforts to build a trade relationship between the UK and China, Buchanan has recorded, continued to grow because of this sustained—even heroic—engagement.

Prime Minister Harold Macmillan’s government unilaterally relaxed trade restrictions, and by the early 1960s, British firms had begun to export tractors and industrial equipment to China.

The death of Chinese ruler Mao Zedong in 1976, historian David Shambaugh writes, opened the path to a further relationship between Europe and China. “From 1975 to 1980,” he records, “China dispatched dozens of inspection and shopping missions to NATO member states. People’s Liberation Army personnel were shown around important NATO bases and introduced to defence industrialists.” China’s energetic backing for containing the Soviet Union led to it being wryly referred to as the 16th member of NATO.

Even though the 1989 slaughter of students at Tiananmen Square led to sanctions barring weapons exports to China, the economic relationship between Europe and China continued to deepen. The European Union is today collectively the largest importer of goods from China, ahead of the US, and the third-largest exporter to it. Xi’s mission is to ensure that this situation is unaffected by China’s deepening conflict with the US.

Also read: Russia has a window to exploit & defeat Ukraine. Otherwise, it will get sucked into endless war

India’s European challenge

France and India have long nurtured their strategic relationship. From equipping the Indian Air Force and Navy to developing the technical foundations of the Research and Analysis Wing, Paris has become among New Delhi’s most trusted partners, together with Israel and Russia. Backing from Paris was critical to India emerging from sanctions imposed after the nuclear weapons tests in Pokhran. And the two countries collaborate closely in the western Indian Ocean and beyond, scholars David Brewster and Frederick Gare have noted.

Yet, India’s economy is nowhere near as enmeshed with Europe as that of China. And even though Belt and Road Initiative investments are losing their sheen in some European countries, the sheer scale of investment China brings to the table makes it impossible to ignore. And Europeans know that China will have real influence over Russia’s conduct.

To fully capitalise on the rupture opening up between China and Europe on Ukraine, New Delhi needs to speed up long-stalled negotiations on a free trade agreement. Earlier this year, India signed a similar deal with four non-European Union states, but the bigger prize needs to be secured as soon as possible. India also needs to resolve the problematic question of its position on the Ukraine war, and its relationship with Russia.

Xi won’t be walking away from Europe with a win in hand, but his visit will almost certainly ignite arguments about the continent’s geopolitical future. India should learn from China’s long engagement with Europe, and step up its efforts to be heard.

Praveen Swami is contributing editor at ThePrint. He tweets with @praveenswami. Views are personal.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)