It was in the middle of a July night last year when Idris Kadru, in his mid-30s, scrambled for a vehicle to carry his three-month-old son to a hospital. The infant’s body was turning cold and his head was burning with high fever. The nearest hospital from his village Ludbay in Gujarat’s Kutch district was 50 km away. The son died before he could reach the hospital.

This wasn’t just a one-off incident.

Six hundred kilometres away, in a tribal village Kupda, in Dahod district, nine-month-pregnant Sonal Damor met the same fate as Kadru’s son in September. Anaemic and in labour, the ambulance allegedly ferried her from one hospital to another. Hospitals don’t easily admit patients with anaemia if they don’t have a blood bank. She died unable to find admission in a hospital, said her family.

Behind the shining image of a vibrant Gujarat that’s dotted with sprawling industries, high-speed bullet trains and an expansive highways network—all projecting a growth model for India to adopt—lies a creaking healthcare system that’s letting the poor of the state down. Many health centres are just empty. In Gujarat’s tribal hinterland, health experts say that a number of pregnant women are dying on their way to hospitals as these ghost community health centres are unhelpful in the absence of MBBS doctors and other medical staff. Nutritional deficiency is spreading malnutrition. It’s a story of systemic neglect and reluctance of young medical professionals who don’t want to work in the villages.

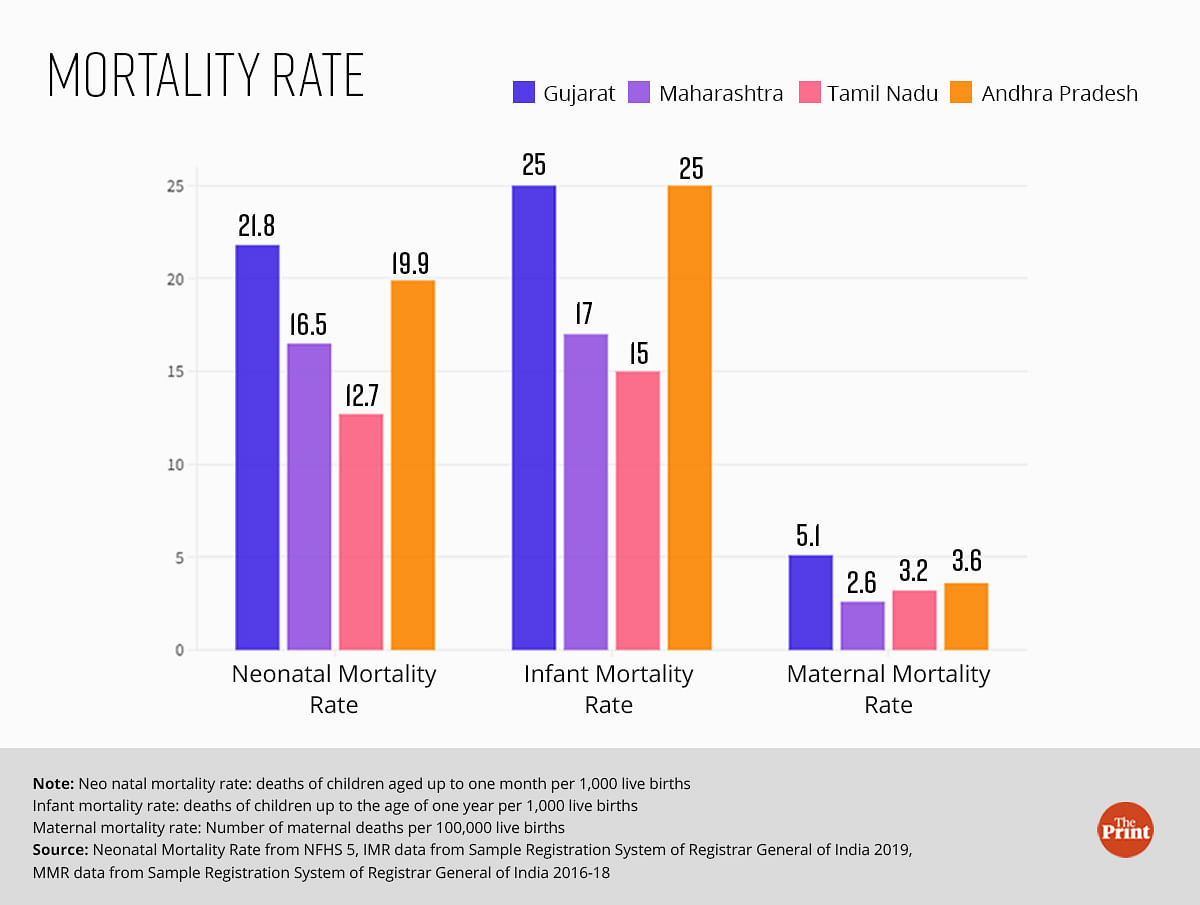

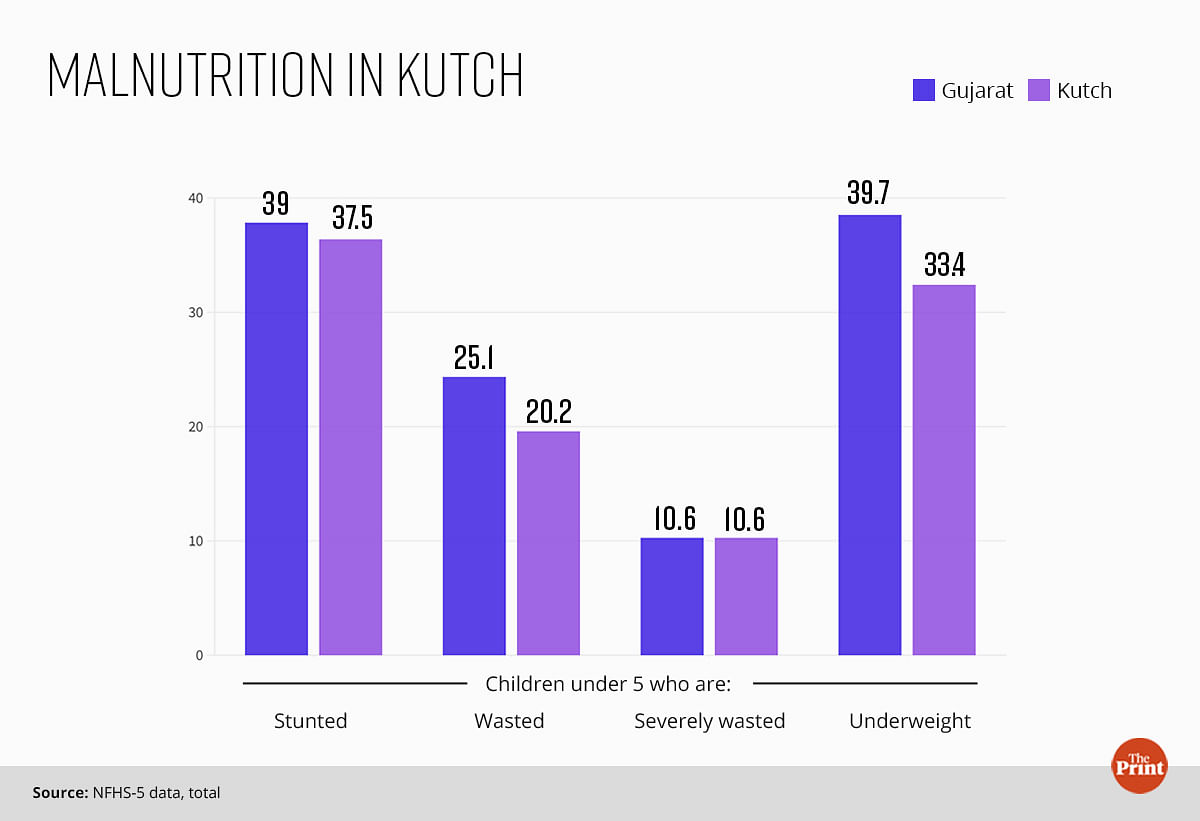

With the steady rise in Gujarat’s per capita income and revenue, the state is counted at par with other rich states like Tamil Nadu and Maharashtra. But on child malnutrition, Gujarat is worse than Bihar and Odisha. Malnourished children in Tamil Nadu are almost half of Gujarat’s.

The growth is not reaching the last mile where malnutrition rules and healthcare screams for urgent care. While the questions on debilitating healthcare facilities often echo in the state assembly, a change on ground remains elusive.

Between 2018-19 and 2021-22, Gujarat’s per capita Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP) grew at an annualised rate of eight per cent. Between 2022-23 and 2023-24, the state’s GSDP is projected to grow at 13 per cent. Two rounds of the National Family Health Survey (NFHS), conducted between 2014-15 and 2019-21, show that the prevalence of anaemia in women aged 15-49 years in Gujarat increased by 12.5 per cent. In the same period, anaemia in children aged 6-59 months also increased by 17 per cent in the state.

“In Gujarat, over many years, the main political priority has been given to industrialisation and industries. That is the state’s overall macro-economic strategy. The social sectors have lower priority in the state and health is part of it,” said Prof. Dileep Mavalankar, former director of Gandhinagar-based Indian Institute of Public Health, country’s first public health university.

Also read: Modi’s yoga mat to Nagaland honey, NECTAR is taking Northeast to Japan, Netherlands

Story on the ground

ThePrint visited PHCs and health and wellness centres (HWCs) in Kutch, Mahisagar, and Dahod that were freshly painted and well-stocked with supplies. What stood out was the acute shortage of doctors and trained healthcare workers.

Some centres had no allopathic doctors to either dispense the medicines or to run regular out-patient-departments. The pharmacists were handing out medicines and delivery tables were pushed to the corner for lack of trained staff to conduct deliveries. In a PHC at Dahod, the cleaning lady was dressing a wound with rusted scissors even though a nurse was present.

In many anganwadi centres in the three districts, the records of pregnant and lactating women and malnourished children were missing.

ThePrint made several attempts to contact the Gujarat health department’s principal secretary Dhananjay Dwivedi and health commissioner Harsadkumar Ratilal Patel by visiting their offices, but could not get a response. Visits and calls were also made to the offices of commissioner of women and child development department K K Nirala and deputy director for nutrition and ICDS Neha Kanthariya. But no one was available for a comment.

Also read: Where are the women in Pran Pratishtha? Durga Vahini says they are sidelined

Doctor is in town, not in village?

A thick layer of dust covers cartons of medicines in the HWC on the road leading to Ludbay village. Work desks, stethoscopes, mattresses and stretchers lie unpacked in a room. And dry animal excreta on the floor soils the doctor’s room.

The HWC, three kilometres from Kadru’s home, could have been the first port of call for his son, provided it was functional. The two-room building has been shut for months because the post of a Community Health Officer (CHO), who heads the centre, is vacant.

“If a doctor comes to this centre, he leaves within months. If this centre has a doctor, then villagers will visit for treatment,” said Jat Cheal, a resident of Ludbay village.

But in July, this abandoned building was buzzing with activity when news of many malnourished children in the village hustled teams from the block and district offices to Ludbay. A CHO was posted at the HWC. But when the matter lost steam, villagers alleged, the centre was shut again.

For village sarpanch Jabbar Jat, the death of Kadru’s son came as a wake-up call. He found that four other children had died in the village in the last few weeks.

“I found out that the children who had died were very weak. I visited block and district offices and filed applications under the Right to Information Act to know why there are no doctors in the health centres in my panchayat. But I received no responses,” said Jat, who has six villages in his panchayat Ludbay Juth.

Soon after Kadru’s son died, Mumbai-based paediatrician Dr Jayesh Kapadia organised a health camp in two villages of the panchayat and found 37 out of 300 children malnourished.

The village’s anganwadi centres, which are responsible for ensuring that nutrition reaches children’s plates, rarely opens, the villagers alleged, depriving children and pregnant and lactating women of hot-cooked meals. The nearest HWC had no CHO and the PHC, 22 km away, was being run by a lone Ayush doctor. For their health needs, villagers travel to Bhuj, 90 kilometres away, covering a 16-kilometre stretch, which has no road.

The anganwadi worker was fired in August. And female health workers, auxiliary nurse midwives (ANMs), and Asha workers frequented the homes, counselling mothers on what to feed their children. The state government conducted its own surveys to find out malnourished children. Their data matched Dr Kapadia’s.

The government found 36 children malnourished, out of which 13 were in severe condition. As per the district records, between January and July 2023, eight children (and not five as Jabbar had stated), died in the village. These were children up to the age of six months. But malnutrition was not recorded as the cause in any of these deaths.

“We found that most of the children died of fever or other medical complications like birth asphyxia. Only one child out of these was severely malnourished,” said Dashrath Pandya, in-charge of women and child department, Kutch.

Child malnutrition in Kutch has been a long-standing problem.

“It is a cycle of poverty, poor hygiene, hunger, diseases and overall drop in immunity in children, which results in malnourishment. Just giving medicines is not going to help,” said Dr Kapadia, who has been organising health camps in Kutch villages for 17 years now.

Nomadic tribes, low literacy levels, early marriage and frequent pregnancies result in women having more children, he said. Only 24 per cent women in Kutch have received 10 or more years of schooling as compared to almost 34 per cent in Gujarat. Nineteen per cent women between the age of 20 and 24 years in Kutch were married when they were minors. In Gujarat, this number is almost 22 per cent, according to NFHS-5 data.

Also read: Kunal Bhardwaj is corporate India’s rainbow warrior who ran 7 continents with the pride flag

The bane of rural postings

The problem of malnutrition and infant deaths are related to the under-staffed and un-doctored health centres. It’s a crisis of confidence and access for the people. The state has spent on health infrastructure, but it’s a human resources problem. The deaths in Ludbay village have failed to populate the public health centre (PHC) at Desalpar that has remained without an MBBS doctor since the last five years. The sparkling-clean building that came up sometime in the last three years with its multiple rooms, medicine stock and an ambulance on stand-by has a lone Ayush doctor, who prescribes allopathic medicines without any training in allopathy. The delivery room, equipped with an incubator, running water and a delivery table, is unused.

“The doctors don’t stay in this area as there are no quarters for them. The village has poor road connectivity and no phone network. The local bus operates only once daily from Nakhatrana block. If you miss it, you cannot reach the PHC,” said Priyanka Gohel, Ayush doctor, who has been serving there for the last three years because she has a room in a village. She added that her requests to the district and block officials for more staff has fallen on deaf ears.

The Nakhatrana block and Kutch district officials say they are helpless. Posting in the district is least preferred as the population there is sparse and the expansive, remote desert villages are miles away from the towns and the cities, they said.

“We inform the district about vacant posts regularly. But no one wants to work here. The doctors leave before they complete their one-year bond to work in rural areas,” said A K Prasad, taluka health officer, Nakhatrana.

Data presented in May 2023 in the Gujarat assembly shows that many new MBBS doctors pay their way out of serving in rural areas. Between 2020 and 2023, around 1,800 MBBS graduates paid the bond amount of Rs 10 lakh instead of working in rural health centres.

For Nakhatrana’s seven PHCs and two community health centres (CHCs), there are only three MBBS doctors, all of them posted in the CHCs. Gohel is the only doctor (Ayush) for seven PHCs. Delivery happens in only one PHC of Nerona by a staff nurse. Out of the 46 HWCs in the block, eight are non-functional because of lack of CHOs.

The neighbouring Lakhpat block is no different. There are no MBBS doctors and the block’s four PHCs are run by Ayush doctors. And for its 20 HWCs, the block only has 14 CHOs.

Gujarat, however, is not the only state struggling to fill its rural postings with doctors and other health human resources. It is a nation-wide issue and the central government has tried to make several interventions such as increasing seats in medical colleges and giving grace marks for post-graduate entrance exams for serving in rural areas. In 2019, the government also introduced a short-term course to create a cadre of CHOs, to fill the posts at HWCs. But these measures have failed.

To fix the manpower shortage in difficult‑to‑access areas, some states have made local interventions. In 2009, Chhattisgarh established the Rural Medical Corps (RMC) through which the state provides financial incentives, housing, life insurance, and extra marks during postgraduate admission to health workers and doctors for a minimum four years. Within a year, the RMC helped reduce the vacancy rate to half — from 90 per cent to 45 per cent — across facilities.

Other states like Tamil Nadu, Assam, and West Bengal have established recruitment boards that ease bureaucratic hurdles and fill vacant medical posts quickly at the district level.

At the Kutch district office, the health official said that over 1,000 applicants apply when vacancies are announced, but barely 10 candidates show up for the interview.

“The candidates leave as soon as they get hired in other districts. The problem will be solved if locals can be hired here,” said the district official.

Also read: Rise of veganism has been hard in vegetarian-friendly India. Milk is the final frontier

The missing nutrition

In January 2024, Gujarat announced how a pilot project to address malnutrition in Kheda district made important gains. For three months, health and nutrition teams implemented the existing programmes in a campaign mode. As a result, 127 out of 150 severely malnourished children moved to normal weight category. Fifteen children became moderately malnourished. Eight children migrated. The success of the pilot has encouraged the district to expand the campaign to 500 severely malnourished children in 10 other blocks.

But Ludbay has no such luck.

Six months after the deaths, the neglect is stark. The anganwadi centre remains shut, except for a few minutes in the afternoon when the helper brings the day’s lunch, which she prepares at her home. Some of the children take the anganwadi meal home in a bowl.

The meal, which should comprise green vegetables, legumes and fruits, is only a concoction of boiled rice mixed with spices. And it fails to attract children who gather near the building with a penny in hand to buy cheap, colourful chips from a cart parked outside the anganwadi centre.

Six-month-old Wasim in Ludbay village is severely underweight for his age. Her mother, Jannat, says she has received no help from the anganwadi centre. | Sonal Matharu | ThePrint

And Ludbay’s poverty and educational backwardness doesn’t help its case either.

“In 2019, the state changed the rules for hiring anganwadi workers. We can now select women only from the same village who have studied till 12th class. Education level of women is poor in the region. We are unable to find eligible candidates,” said Pandya.

If after three rounds of hiring the administration is unable to find any candidate, then they can relax the eligibility to 10th pass, added Pandya.

In the house next to Kadru’s, another child struggles to get to his right weight even as his mother remains helpless. Six-month-old Wasim’s weak body and wrinkled skin is hidden under layers of loose clothes, traditional ornaments and dollops of kajal. Weighing only 4.5 kg (ideal weight is between 6 and 7 kgs), the child quietly sits in a corner when not in his mother Jannat’s arms.

In the same house, two-year-old Zareena is sleeping on the floor, her dress covered in her own excreta. Too weak and stunted for her age, she doesn’t play with other children when awake. Her mother, Ehsani, can tell the difference between Zareena and her other kids, but she doesn’t know what to do.

“The Asha and the anganwadi worker told me earlier to feed her anything, but increase her weight. They gave me the packet (take-home ration), but the food was consumed by others in the house,” said Ehsani who lives in a large joint family that engages in labour work, be it on farms or otherwise.

Anganwadi workers are expected to act as a watchdog of malnourishment—they weigh the children and measure their arm circumference every month to check if they are slipping into malnourishment. If the growth chart of the child starts to dip, the worker has to immediately increase the food given to the child, refer him or her to the nearest PHC to check for infections. And field workers have to visit the child’s home to ensure the child is getting a proper diet.

“Children rarely become a case of severe acute malnutrition overnight and die. It’s a process. Malnourished children should be identified in the first month itself when their weight starts to drop,” said Dipa Sinha, economist and public health expert who also writes on food and malnutrition issues.

In anganwadi worker’s register, moderately malnourished children are highlighted in yellow and severely malnourished in red.

But the names of Wasim and Zareena are not marked in red in the records. And the mothers claim that neither the Asha worker nor any other field worker visited their home or advised them to take their children to the Nutrition Rehabilitation Centres (NRC) at the block or the district.

Also read: IAS officer KK Pathak is the TN Seshan of Bihar schools. But can fear bring reform?

Empty beds at nutrition rehabilitation centres

Four beds at the Child Malnutrition Treatment Centre (CMTC) at Nakhatrana have been lying vacant for the last two months (November-December). Toys for children dumped on one of the beds. The centre is home for moderately malnourished children who are fed diet rich in fats and protein by the nutritionist manning the centre even as such children lie in the villages of Kutch.

In September, the centre had five children, which dropped to two in October. This is a drastic fall as compared to at least 15-20 children who were admitted each month till about two years ago. The primary reason, according to nutritionist Rashmita Maheshwari, is the cessation of free state-sponsored transport service called Khilkhilahat.

“The numbers at the centre have been dwindling since the Khilkhilahat van service stopped 1.5 years ago. Under Khilkhilahat, a mother could bring their child in the morning and take them back home in the evening. Throughout the day, we could feed the child. Now with no transportation, women cannot come from far off villages,” said Maheshwari.

A similar halt in services is seen at the 20-bedded NRC at the district hospital in Bhuj as well where severely malnourished children are admitted. 25 children were admitted to the centre in April 2023. That number dropped to four in November and only one child was in admission by the first week of December. The NRC has allegedly not received the grant to buy food for the children admitted there, said the staff.

“The staff gets food from their homes or put in their own money to buy milk, vegetables, fruits for the children. We have requested the district authorities, but nothing has happened yet,” said Neha Ba Jadeja, staff nurse at the NRC.

Eleven-month-old Avni Kohli is the only child at the NRC when ThePrint visited the centre in December. At the NRC, her weight increased 500 grams in 10 days. | Sonal Matharu | ThePrint

The district health officer who didn’t want to be named said that to avail Khilkhilahat‘s services, the children and their mothers must stay at the NRC for 15 days.

“The Khilkhilahat can only bring the family once to the centre on the first day and then drop them back to the village on the 15th day. Daily service is not allowed. That is why the numbers in the NRC and CMTC have dropped marginally,” said the official. The funds for the NRC, he said, are being stuck due to administrative hurdles.

Also read: Tamil Nadu is the new China+1 for shoes. Crocs, Nike, Adidas foot India’s manufacturing push

A photo on the wall

A framed photo of 22-year-old Sonal Damor hangs on a plastered wall of her mud house in Kupda village in Dahod. A garland of plastic flowers wrapped around it. In September, as Sonal was taken in an ambulance for the delivery of her second child, the family waited eagerly for the news of the baby to arrive. But Sonal died.

Young women across Dahod are losing lives either during childbirth or due to post-delivery complications. Like Kutch, the healthcare centres in the villages of Dahod stocked with medicines and equipment are unable to serve lives.

At Salra PHC, 1.5 km from Sonal’s house, the delivery bed is pushed to the wall. The room has been abandoned for two months (October-November) since the staff nurse left. The new nurse is not trained to conduct deliveries. When ThePrint visited the PHC, the doctor on duty was attending a family planning camp at Fatehpura block. The centre had one visiting patient whose wound was being cleaned not by a nurse but a cleaning lady.

The block hospital of Devgarh Baria, which caters to a population of over three lakh that’s spread over three blocks did not have a gynaecologist and a paediatrician till about two months ago, said the health workers present there.

The large number of vacancies in Dahod also made news in November when new reports said that data presented in the Gujarat Assembly in September showed that at 95 per cent the district has the highest vacancies of doctors in the state. Banaskantha at 93 per cent and Kutch at 77 per cent follow.

The issue of vacant medical posts is raised in almost every assembly session, said Vadgam MLA Jignesh Mevani. But nothing changes on the ground, said the Congress politician.

“Across Gujarat, you will find structures of PHC and CHC, but you will hardly see any medical facilities and staff inside. This is the condition even in the constituencies of the state health minister and the chief minister of Gujarat. Health is not the state’s priority. Under the glitter of developing Gujarat, these issues get hidden,” he said.

Also read: Gig dream is fading for Uber, Ola drivers. They are forming picket lines & support groups

Falling off the govt radar

At the Dahod district office, chief district health officer Uday Kumar Tilavat’s data sheets tell a perfect picture. Showing the data charts to ThePrint, Tilavat explained how the delivery of services is crossing the 90 per cent mark. A few exceptions, he said, are because of people’s reluctance to use them.

“Our Ashas accompany women for deliveries even at night, 108 ambulances are working, we are all on the ground working. But even if these (services) are being made available, are these being taken? It takes time for people to accept change,” he said, adding that women’s low education and multiple pregnancies are the causes of high incidence of anaemia in the district.

But blaming the families for not accessing health care doesn’t explain the grim numbers.

Dipa Sinha pointed to an indicator that has not been captured in Tilavat’s excel sheets. “There is no trust in the system because the system has not worked for the people so far. A lot of the human resources required at primary level don’t have to be MBBS doctors. Well-trained manpower can cater to the needs in the rural areas. People access services when they feel they are getting any benefits from the health centre,” said Sinha.

When Sonal’s labour pains started, her family took her to Fatehpura CHC, six kilometres away. But the CHC doctors allegedly referred her to Dahod district hospital, which is 70 km from her village.

“No hospital wanted to risk admitting her as she was anaemic,” said Shailesh Damor, Sonal’s husband.

Dahod, a tribal district bordering Madhya Pradesh, is only 200 km from Ahmedabad and is connected through a smooth highway. It is one of the two under-developed districts in Gujarat which are under the aspirational districts programme launched by the Prime Minister in 2018. The programme aims to ensure convergence of state and central schemes and measure the progress of socio-economic indicators in the district, including health and nutrition.

But in a district where out migration is high, many young pregnant women are falling off the government’s radar.

“Women do heavy labour till the last day of their pregnancy. Their diet does not improve during pregnancy and when they migrate, the services don’t reach them,” said Neeta Hardikar, executive director, Anandi NGO.

When five-month pregnant Sonal hopped on to a bus to Ahmedabad to become a labourer at construction sites in the city. She never received hot-cooked meals, take-home-ration or monthly packs of oil, pulses and flour under the state scheme, Mukhya Mantri Matru Shakti Yojana.

Since this was her second delivery, she wasn’t eligible for the centre’s maternity entitlement scheme, Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana, which gives Rs 5,000 to pregnant women in three instalments to meet their nutritional needs during pregnancy and lactation period.

At the Anganwadi centre few meters way from Sonal’s house, the register holds no record of pregnant women or growth charts of village children.

“Women don’t come to the anganwadi to eat,” said anganwadi worker Rama Damor who cooks the food at her home. “If they are anaemic, I refer them to the PHC to get iron through a drip”.

Attempts to reach the district ICDS officer-in-charge, Ira Chauhan, through calls and by visiting her office failed.

Meanwhile, Tilavat, blamed the social and geographical factors.

“The eating habits of tribal populations are still not developed. Geographical factors also matter. Soil layer is thin in this region. As a result, nutrition in the food is less. No matter how hard we try, we cannot match the standards in other richer areas,” he said.

Tilavat said authorities are trying to tackle the problem of anaemia and malnutrition. He suggests reducing the measurement statistics. “Then this area won’t be as anaemic or malnourished as it is now.”

Also read: Ennore Coromandel gas leak was a close shave. People are going from hospital to protest site

Cycle of ignorance and neglect

December started on a grim note for Shilaben Khant, community mobiliser and trainer with Anandi NGO. Her WhatsApp groups have been pinging with the news of three maternal deaths in the last two days in Devgarh Baria in Dahod. After the mourning period of twelve days is over, teams of health workers will visit the homes where the deaths have happened for social autopsy reports, which the NGO has been conducting for over 16 years.

“Through the social autopsy, we try to see besides the health services, what are the other social indicators which are equally important for safe delivery. And which ones were not adequately available to the women,” said Khant.

Their findings show that often delays happen at the public health facilities and social factors add to complications in delivery.

ThePrint visited five homes in two districts where pregnant women had died and found that there was no nutritious food added to the woman’s meals once she became pregnant.

“Counselling happens at the anganwadi centres where women are told to eat carrots, green vegetables, apple and banana. But nobody is even trying to understand if these are available at their homes,” said Hardikar.

(Edited by Anurag Chaubey)