New Delhi: Arun Sarma pulls out two tiny jars of saffron from his office drawer—a product of the government’s latest mission in the Northeast. Until now, the coveted spice was only grown in Kashmir. But as director general of the North East Center for Technology Application and Reach or NECTAR, Sarma plans to change that perception. And very soon, saffron produced in the northeastern states of Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, and Sikkim will hit the market. These days though, he and the other officers at NECTAR are facing a dilemma—how to design branding stickers on a glass jar of saffron that is barely a centimetre tall.

NECTAR’s Delhi office at Vishwakarma Bhavan is like a delightful box of unique products from the Northeast, all made with the body’s support. Exquisite bamboo furniture, a vest crafted from premium banana fibre, packages of export-grade turmeric and cinnamon, and a bottle of the world’s most expensive honeys seem to stand in defiance of the typical government office rooms they sit in. They are also iterations of an ambitious initiative to encourage entrepreneurship in the northeastern states, taking premium organic products from remote parts of India to global markets.

Set up in 2012, NECTAR was formed by merging the National Mission for Bamboo Application (NMBA) and the Mission for Geospatial Applications (MGA) as an autonomous society under the Department of Science & Technology. In little over a decade, not only has the centre helped over 150 entrepreneurs find their footing, it has also supported farmers looking to increase their livelihoods.

And the rest of the country sat up and took notice on International Yoga Day in 2020 when Prime Minister Narendra Modi, along with several other ministers, practised their poses on biodegradable yoga mats made from dried water hyacinths that were once choking the Deepor Beel lake in Assam.

NECTAR’s journey is peppered with many such stories of empowering local communities to pursue businesses that are climate friendly and sustainable. But it’s also a story of overcoming strife, distrust, and conflict among tribal groups, breaking language barriers, and fostering trust to facilitate innovation and entrepreneurship.

The key has been working with local changemakers who then mobilise others in the community to participate in the government’s mission.

“With very small interventions from our side, farmers can sell their high-quality products to countries like Netherlands and Japan, instead of getting rid of them at throwaway prices,” Sarma said.

He has devoted himself to the quest of revitalising neglected farmlands and globalising agriculture in the Northeast.

NECTAR has shifted shift from an organisation that worked solely as a funding agency for entrepreneurs to something larger—a catalyst for change.

Also Read: Tamil Nadu is the new China+1 for shoes. Crocs, Nike, Adidas foot India’s manufacturing push

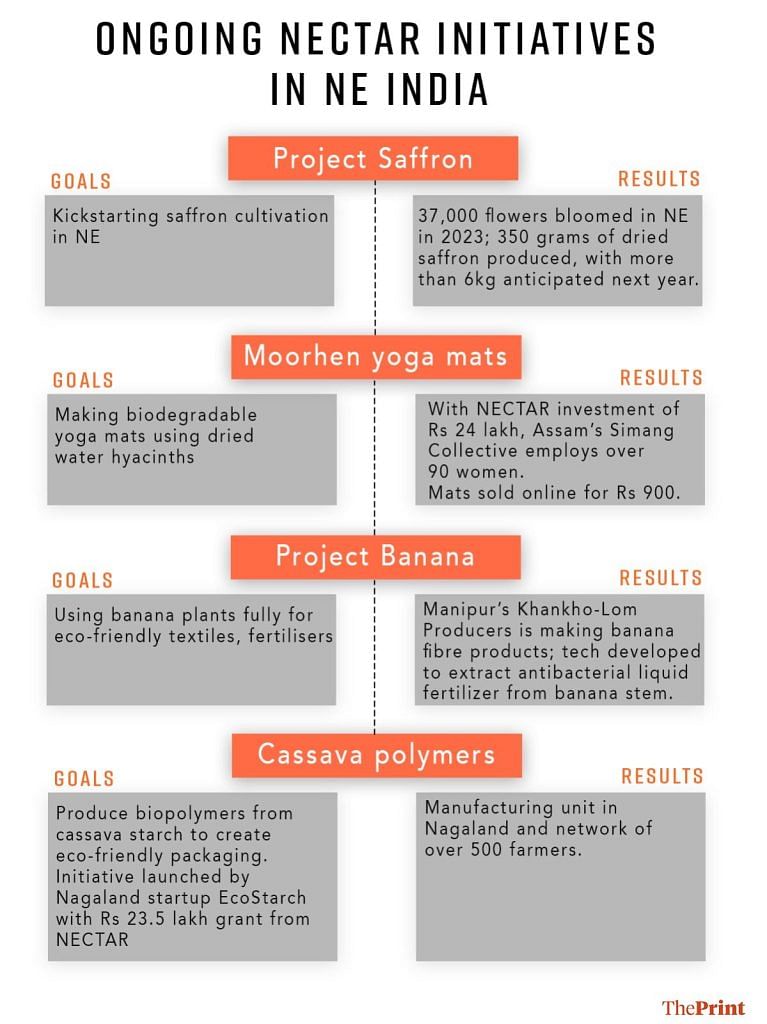

Project Saffron

During the pandemic years, when everyone was laying low, drones hummed over the rolling hills and sprawling tracts of Arunachal Pradesh, Sikkim, Meghalaya, and Mizoram. They were surveying and analysing the soil and climate conditions to identify land that could potentially grow saffron.

Often dubbed ‘red gold’, Kashmir’s saffron is the world’s most expensive spice. Selling for over Rs 3.25 lakh per kg, the crop exceeds even the price of silver.

“As many of the places of the Northeast have similar climate and geological conditions as districts of Jammu and Kashmir, we thought why not grow saffron here?” Sarma said.

Leveraging its expertise in geospatial technology, the NECTAR team was able to identify suitable land through drone surveys and carried out the first trials in Sikkim in 2021.

“In the subsequent trials we expanded to 64 villages across 17 districts—we got very good results,” Sarma said. For the first time last year, over 37,000 saffron flowers bloomed in the Northeast.

Since the project was carried out on a trial basis on small plots, amounting to a total area of 5 acres, the harvest was modest, yielding about 350 grams of dried saffron. But Sarma expects an exponential increase, with saffron cultivation to be expanded to more states beyond Sikkim.

“We are anticipating more than 6 kg next year,” he added. “The price of Kashmiri saffron is Rs 350-400 per gram. However, considering that the Northeast saffron is organically grown and unprocessed while packaging, the price can go higher.”

Polymers from cassava

After Akumtoshi Lkr completed his PhD in ecology and environment from Nagaland University in 2021, he did not want a regular job.

“I wanted to do something that defines who I am, and I found my calling as an entrepreneur,” Akumtoshi told ThePrint. “Entrepreneurship is a new concept for us, people like us usually depend on government jobs.”

Through his startup EcoStarch, Akumtoshi collaborates with cassava farmers in Nagaland to produce biopolymers from cassava starch— used as raw materials to replace single-use plastic products. Additionally, the plant converts its agricultural waste into affordable animal feed.

Although cassava farming has huge potential in Nagaland, farmers only produce it on a small scale and use it as animal feed. “People do not opt for it because there is no market,” he adds.

Through EcoStarch, Akumtoshi wants to prove them wrong. As a scientist, he possesses technical know-how and expertise, but working with NECTAR has helped him build credibility and the government stamp has instilled confidence in farmers too, he said.

“Getting a grant from them was a starting point for us. I am very thankful because it showed their trust in our work,” he added.

With NECTAR’s grant of about Rs 23.5 lakh, Akumtoshi was able to set up a manufacturing unit in Mokokchung district’s Changtongya village on land donated by the local community.

“We are working with about 500 farmers now. Now we are bringing the market to their doorstep—which is very big for the community,” Akumtoshi said. Akumtoshi is pursuing other projects with additional support from another grant from the Biotechnology Industry Research Assistance Council (BIRAC)—including turning domestic waste into animal feed.

That said, Akumtosi struggles with challenges endemic to the region, including high transport costs and small land holdings.

The uncertainties surrounding tensions among different groups, along with language barriers and a general distrust towards people outside their own communities makes initiating such missions very difficult

-Krishna Kumar, technical advisor at NECTAR

According to Krishna Kumar, the technical advisor at NECTAR, the biggest hurdle is logistics. “The landholdings that farmers have are very small—half an acre or sometimes less than that. Any buyer will want large quantities of produce,” he said.

Transporting products from the Northeast to the rest of the country is not difficult, but it comes with a relatively high price tag.

“Unless farmers have a sustainable quantity of produce, no one is willing to transport it. That is why it makes sense to produce high value products in the Northeast. Even if it is done in a small land holding, the value of the produce is high enough to justify the logistics costs,” said Kumar.

Moorhen yoga mats

On International Yoga Day in 2020, Prime Minister Narendra Modi used a unique biodegradable yoga mat made out of dried water hyacinths. For NECTAR and the women-led collective behind the mats, it was a moment of pride.

Rumi Das and five of her friends lost their jobs in the hospitality sector in Bengaluru during the pandemic, and returned to Guwahati in Assam wondering what they would do next. It was during a visit to the Deepor Beel that they hit upon the idea of using the overgrowth of water hyacinths to make yoga mats, while also helping to restore the lake’s ecosystem.

The perennial freshwater lake around 10 km southwest of Guwahati city is the only wetland in Assam to be designated as a site of importance under the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands. But an overgrowth of water hyacinths choked the lake, depleting oxygen levels and causing the fish population to dip. As a result, the birds too stopped visiting the lake, Sarma said.

With support from NECTAR, Das and her friends, now known as the Simang Collective, started using dried water hyacinths to produce mats. However, they hit a bottleneck—drying the water hyacinth took up to 12 days. And if it rained, which it often did, their efforts would be further delayed.

To tackle this issue, NECTAR first turned to IIT-Delhi’s civil engineering department to figure out the correct conditions for drying water hyacinths without making them brittle. With the correct specifications in hand, the centre then approached Indian Oil and Hyderabad’s National Institute of Rural Development and Panchayati Raj to develop a solar-powered hot air oven. NECTAR gave the oven to the women, allowing them to slash their drying time to just 36 hours.

“We also gave them semi-automatic looms and tasked them to supply 700 yoga mats by 20 June 2020,” Sarma said. Overnight, the team became famous for their biodegradable mats, with the government issuing an office memorandum for using them for the 2022 International Yoga Day too.

“With just an investment of about Rs 24 lakh, we were able to empower them,” Sarma pointed out.

Today, the Simang Collective provides employment to over 90 women in Assam and the mats retail online for Rs 900 on their website.

Getting bang from bananas

NECTAR’s pursuit of sustainable and profitable solutions goes beyond the Deepor Beel wetlands. In Assam’s Goalpara district, the century-old Daranggiri market— Asia’s largest banana market—was a perfect testing ground for products made from waste. According to Sarma, the market also struggles to manage its agricultural refuse.

With NECTAR’s support, Manipur’s Haojathang Haokip, director of Khankho-Lom Producers Company Ltd, is now creating products from banana fibres—extracted from the plant’s stem. The company is part of a larger NECTAR mission to utilise the entire banana plant. These uses span from ecofriendly textiles to fertilisers.

Communities here were being exploited for their resources. For me the biggest motivator was using my privileges to bring about a change

-Arun Sarma, director general, NECTAR

“Banana tree consists of the purest form of water, just like coconut. If you take out the stem, you can extract water from it,” Sarma explained.

“This water is highly antibacterial. It can also be processed into high-quality fertiliser.”

He added that the Navsari Agricultural University in Gujarat developed the technology, and named the liquid fertiliser ‘Avon’.

After water is extracted from the stem, the leftover fibres can be used to make eco-friendly textiles.

“Now we are going to buy trees from farmers at low cost and make fibres, liquid fertiliser, and vermicompost from them,” Sarma said.

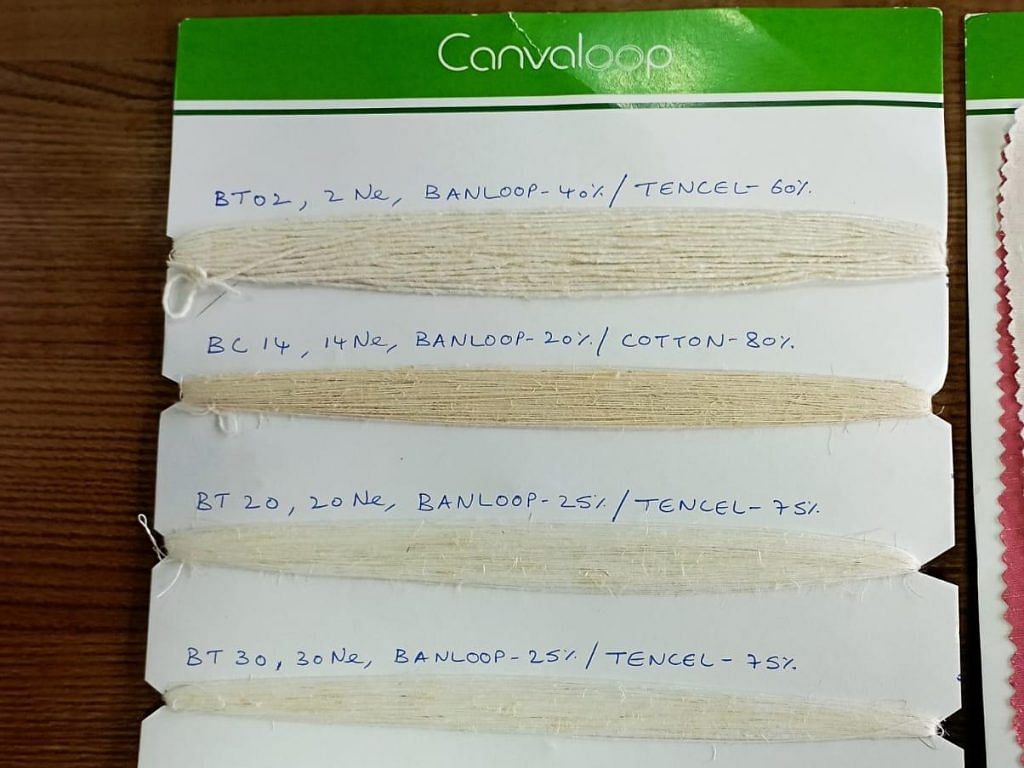

NECTAR is working with textile companies to test different blends of the cloth. Sarma’s office houses samples of cloth made from a mix of banana fibre and cotton, while a fully finished jacket is mounted on the shelves of his office.

“We are in talks with a company that will buy all of our banana fibre from us,” he added. In a week, one manufacturing plant can produce a metric ton of fibre, selling for Rs 90 to 100 per kg.

“From a banana tree that people were going to throw out, we can make a lot of money from the fibre alone,” Sarma pointed out. The team is also exploring creating vegan leather from banana fibres.

Unfortunately, the ongoing conflict between Kukis and Meiteis in Manipur has affected Haokip’s business, although he expresses hope that conditions will improve soon.

Conflict among tribal groups across the Northeast is among the many challenges that NECTAR faces in the region.

“The uncertainties surrounding tensions among different groups, along with language barriers and a general distrust towards people outside their own communities makes initiating such missions very difficult,” Kumar said.

Akumtoshi also made note of the historical exploitation of Nagaland’s resources by external traders. “People have a distrust of traders from outside because they have been exploited,” Kumar agreed.

Also Read: Morbi is India’s undisputed tile champion. Now this Gujarat town is eyeing China’s crown

Honey & buckwheat on the menu

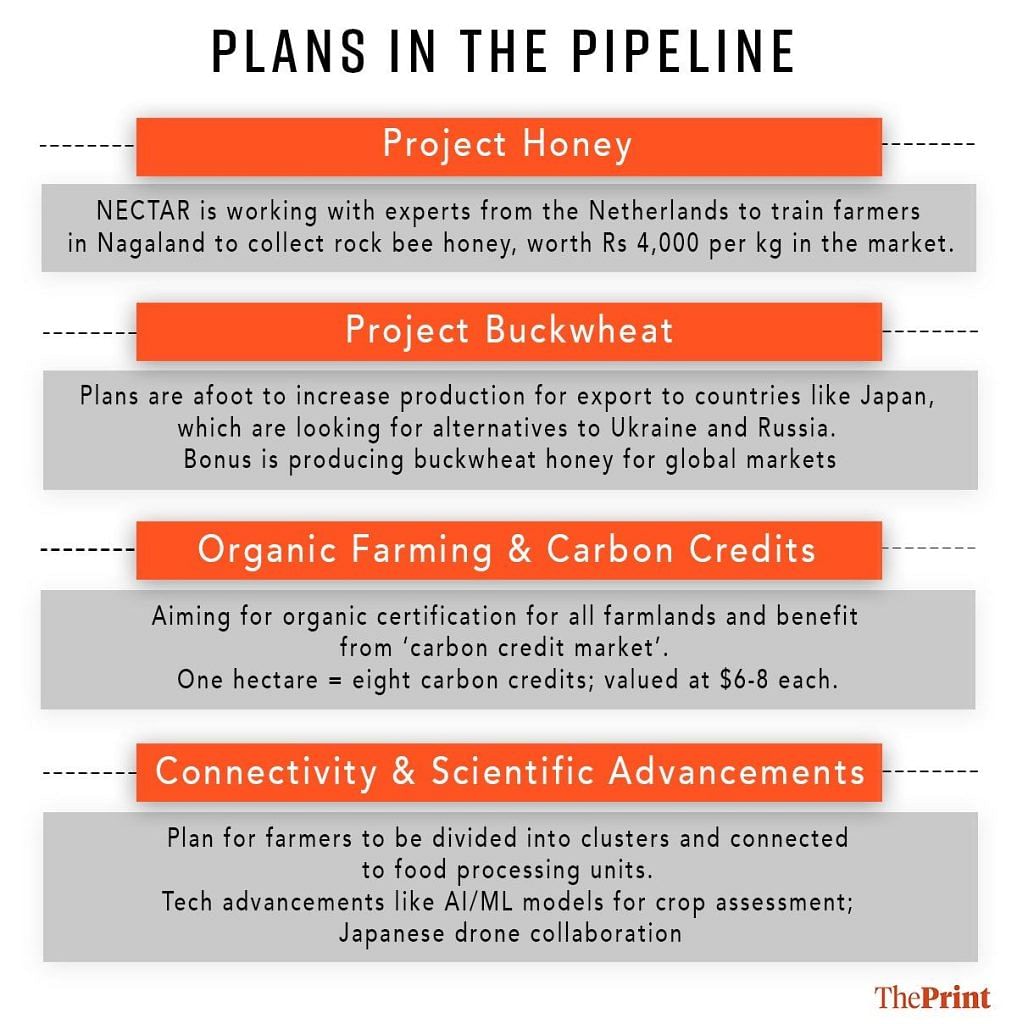

NECTAR is now gearing up for Project Honey—set to be run on ‘mission mode’ just like the saffron project. Sarma opens a sample bottle of rock bee honey from Nagaland, highly prized for its antioxidants and antibacterial properties.

“Its value is over Rs 4,000 per kg in the market. It is only available at a few places on the Indo-Myanmar border. Only few people are trained to collect it,” Sarma explained.

The honey is found in some areas of Nagaland, but because local collectors lack access to processing technology, they sell the raw product to intermediaries for a very low price. These buyers then process the honey and sell it at a premium.

Now, NECTAR is working with experts from the Netherlands who will train farmers in Nagaland to collect, process, and package this honey. The organisation will also help these communities access essential production equipment.

Another avenue that NECTAR is exploring is the export market for buckwheat—a gluten-free alternative to traditional atta and maida.

“In Rajasthan and Gujarat, people consume products made of buckwheat during fasts,” Sarma explained.

But India is eyeing a far more lucrative buyer for the product. Soba—a popular Japanese noodle—is made from buckwheat.

“Japan imports 45,000 metric tonnes of buckwheat from Ukraine and Russia. But because of the war, they are looking for alternatives. They know that the Northeast grows buckwheat—but it is barely 500 metric tonnes,” Sarma said.

According to him, the Meghalaya Farmers Empowerment Commission is already in talks with Japanese officials about scaling up buckwheat production.

An added advantage of cultivating buckwheat is that it opens the door to producing buckwheat honey, which is sold at a premium in the global market.

Local entrepreneurs are becoming bridges between indigenous crops and global markets like Japan and the Netherlands, thanks to NECTAR’s strategic interventions.

Organic farming, carbon credits

Sarma says it pains him to see vast stretches of land lying idle and unfurrowed in the Northeast, especially since most of it is fertile enough to support organic farming.

“We are trying to make sure that all these farmlands get organic farming certification—a process that takes two years,” he said.

His vision is to eventually make farmers in the Northeast beneficiaries of the carbon credit market, allowing them to earn monetary benefits for reducing carbon emissions. If successful, this initiative would be the first of its kind for the Indian government.

“Organic farming on 1 hectare of land is worth 8 carbon credits. Each carbon credit can be worth $6-8 at present. Farmers can thus directly benefit from this,” Sarma said.

Such initiatives mark NECTAR’s shift from an organisation that worked solely as a funding agency for entrepreneurs to something larger—a catalyst for change. All the entrepreneurs it supports are now connected to e-marketing platforms, allowing them to reach wider markets.

Beyond helping individual entrepreneurs, NECTAR is also supporting various scientific activities to connect the agricultural sector of the Northeast to the global market.

A plan is in place for farmers to be divided into clusters and connected to food processing units.

“Once we have such connected channels, the products will become more affordable for the end consumer—and farmers will be able to directly benefit from it,” Kumar said.

The NECTAR team is also working on developing models that use artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) for crop assessments.

“One interesting project we are trying to do with Japanese collaboration is using drone technology and high-resolution imagery—you can calculate the sweetness of oranges, for example,” Kumar explained.

This innovation means that prospective buyers can simply get an aerial survey done to locate the best produce, eliminating the need for physical visits.

“The Ministry of Agriculture has tasked us with using aerial surveys to calculate the productivity of the crop. These technologies are especially useful in areas like the NE where farmers practise multi-cropping,” Kumar said.

‘We are the catalyst’

Under the erstwhile National Bamboo Mission, the team worked with stakeholders to construct more than 42 lakh square feet of bamboo structures across India, ranging from schools in Naxal-affected areas of Chhattisgarh to “igloos” in freezing Ladakh and classrooms in Delhi University colleges.

The same collaborative approach permeates NECTAR’s diverse initiatives.

“There are agencies who have the capability to develop products, those who can run the production unit, and those who can actually execute (projects) on the ground. We are the catalyst—we support all these stakeholders to take the product to the market,” Kumar said.

Entrepreneurs like Akumtoshi are now becoming bridges between indigenous crops and global markets like Japan and the Netherlands, thanks to NECTAR’s strategic interventions.

“Communities here were being exploited for their resources,” Sarma reflected. “For me the biggest motivator was using my privileges to bring about a change.”

On Kumar’s table, an elegant, shiny clay teapot bears the NECTAR symbol. As he holds a matching dark brown cup, Kumar recounts the story of how a community in Meghalaya successfully fought the taboo against unmarried women touching clay. In doing so, they perfected the process of crafting these microwave-friendly tea sets.

Now, he added, a top scientific institute in India has been trying to get in touch with these women to understand and recreate the technology. “With small interventions we have helped promote products that have caught the interest of scientists,” Kumar said. “It’s a matter of great pride for us.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)