New Delhi: Jagveer Singh regrets the day he spotted a billboard advertising a lucrative career in driving as he passed the Gurgaon-Delhi toll tax booth. It was for Ola, then a promising new ride-hailing service, and promised a dream income of Rs 1 lakh per month. Convinced it would turn his life around, he took the plunge. But nine years on, his finances are in dire straits. “We’re all deeply depressed, in a debt trap, and have absolutely nowhere to go,” Singh says, echoing the plight of lakhs of other drivers.

The initial allure of ride-hailing services was irresistible. Attractive incentives and the chance to be their own boss painted a rosy picture for India’s youth. Uber and Ola drivers were the pioneers, riding the wave of the gig economy’s promise. But dwindling incentives from app companies, skyrocketing fuel prices, and policy paralysis have thrust these drivers into a debt nightmare.

As India’s employment landscape reshapes, with factory floors slowly losing ground and flexible gig opportunities attracting more takers, the need for policy attention is urgent. This booming sector deserves the same level of care and attention as Make in India—especially crafting robust policies to Make it Flex in India.

The gig economy, however, is stuck in a policy vortex due to the lack of clear definitions—are the workers self-employed, freelancers, or entrepreneurs? And what benefits and rights are they entitled to? So far, there’s no law regulating the gig market, but now states are stepping up, one at a time, to get a grip on the situation.

Rajasthan became the first state to pass a law, the Gig Workers (Registration and Welfare) Act 2023, this year. This groundbreaking law streamlines gig worker registration, offering them security, insurance benefits, and a grievance redressal mechanism, among other provisions. On Christmas Eve, Telangana’s newly appointed Chief Minister Revanth Reddy announced a Rs 5 lakh accidental insurance plan for cab drivers and gig workers. He also said the state was hoping to replicate its version of Rajasthan’s law in the next Telangana budget session.

A car is a big investment and the EMIs are high. A lot of drivers purchased cars via loans from private financiers and struggle to pay off their EMIs today. They now find themselves in crippling debt traps

-Akriti Bhatia, domain expert & researcher

Amid state-level action, the Congress party’s All India Professionals’ Congress (AIPC) radically declared gig workers as professionals. Activists like Nikhil Dey, who helped draft Rajasthan’s law, are actively pushing for similar legislation in other states. The University of Pennsylvania has conducted a soon-to-be-published study of 10,000 gig workers from major cities all over India. And NITI Aayog has announced that India is the “new frontier” of the global gig workforce that’s spurring an “economic revolution”.

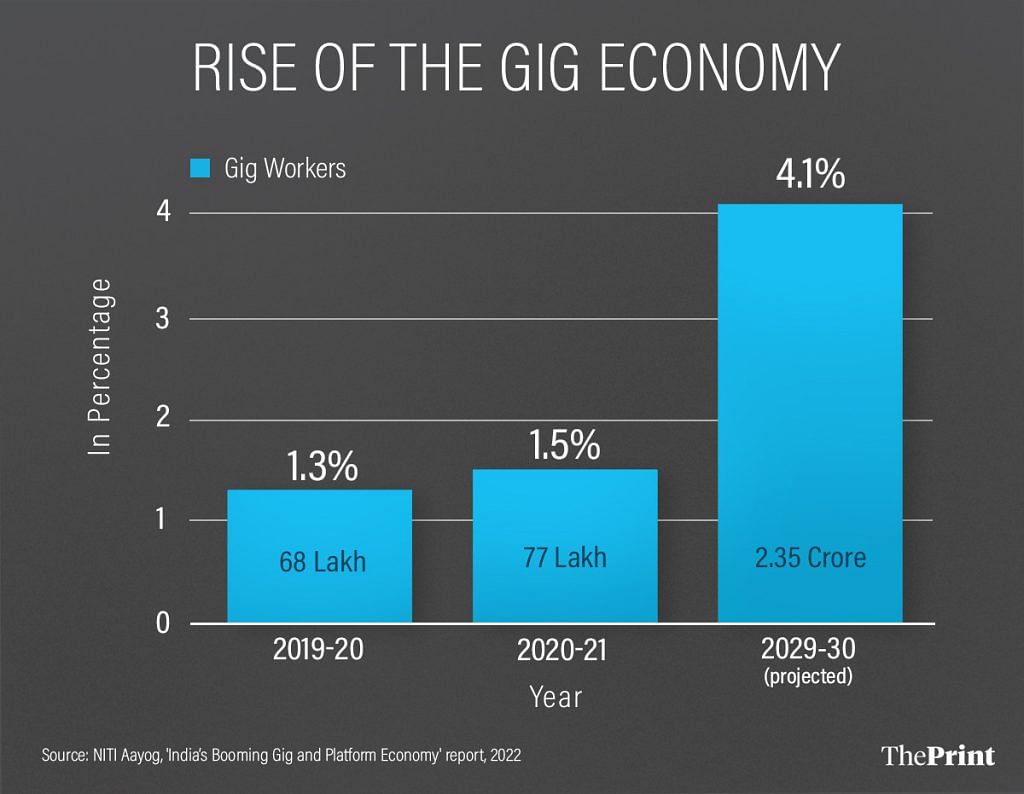

Gig workers struggle to unionise, but they do represent a burgeoning force. Shaik Salauddin, national secretary of the Indian Federation of Transport App-based Workers, often described as India’s “most powerful Uber driver”, is at the forefront of mobilising gig workers to demand their due. “We currently have 77 lakh gig and platform workers, and by 2029 this figure is set to balloon to 2.35 crore,” Salauddin says. “There should be laws protecting the interests of gig workers. Urgent intervention of the government is necessary.”

Also Read: India’s gig workers need urgent social security. But Gehlot’s new law isn’t the answer

Trapped in the Great Gig Dream

In August 2015, Jagveer Singh sold his small mobile and photostat shop and rolled the dice on a brand-new Hyundai Accent. He was going to revolutionise the way Indian commuted in cities and earn a ticket into the middle class, Singh says of his aspirations at the time.

The revolution is now a humdrum fact of life, but he is struggling to stay above water. “We were told we’ll earn Rs 1 lakh to 1.5 lakh by driving for Uber-Ola. Ten years later, I barely take Rs 500 a day home,” Singh laments.

Most gig workers in India are stuck in debt traps and have bad credit, according to domain expert Akriti Bhatia, who has a PhD in India’s gig economy from the Delhi School of Economics and is part of the upcoming UPenn study on cab drivers. “A car is a big investment and the EMIs are high. A lot of drivers purchased cars via loans from private financiers and struggle to pay off their EMIs today. They now find themselves in crippling debt traps,” Bhatia tells ThePrint over the phone.

On a sunny day at Delhi’s Jantar Mantar, Singh stands alongside his colleagues, armed with precise calculations in his diary.

“Our base fare is Rs 53, and we receive Rs 7.27 per kilometre, with an additional Rs 1 for every minute during a ride. However, 40-50 per cent of this is cut in various charges. We’re really not making anything,” he says, while others nod in agreement.

The drivers pull out screenshots to show the hefty deductions of app-based companies, claiming that the share demanded by both Ola and Uber is completely arbitrary.

According to the 2020 Motor Vehicle Aggregators Guidelines, 80 per cent of the total fare should go to the driver, with the aggregator companies’ commission capped at 20 per cent. Receipts of rides reviewed by ThePrint indicate that ride-hailing companies often deviate from these regulations.

Despite repeated attempts to contact Ola and Uber via email and through their public relations officers, neither company responded to queries.

The story of diminishing income echoes across various online platforms. For instance, ThePrint reported in May about how Blinkit delivery agents, who dreamed of taking home Rs 50,000 are now struggling to make ends meet. Some of these workers said they saw more dignity and economic prospects in becoming drivers for cab aggregators.

Some customers taunt me for the way I look and dress. Some do try to have a conversation and understand my predicament, but others simply make faces

-Dinesh Kumar, cab driver

However, those already working as drivers for such platforms discourage making the switch. And some are even leaping delivery services, according to Bhatia. “This kind of mobility and hierarchy within the gig economy is evident among drivers. A lot of drivers are switching to delivery work because the investment is cheaper,” she explains.

Cabbies are having to fight tooth and nail for the basics. Drivers in Delhi are now demanding fares competitive with government-regulated rates for kaali-peeli (black and yellow) taxis. Ola and Uber drivers recently went on a strike in Chennai, demanding fare regulation and ban on bike taxis. In Bengaluru, drivers are pushing for the setting up of a driver’s cooperation board.

Drivers are also trying ‘creative’ ways to get their grievances heard. In Delhi, there’s talk of a ‘digital strike’ to impact companies draw their attention.

“We’re anyway in so much debt, we can’t go on strike and miss work even more. So we’ve gone on a digital strike, where we cancel rides on the app. Repeated cancellations affect customers and companies finally take note,” says Arun Paswan, founder of the driver advocacy association Chaalak Chaupal.

The idea, Paswan explained, is that customers will cancel trips on cab aggregator apps and go with the drivers individually. The plan includes enlisting the support of customers by personally informing them about the issues that striking drivers are facing.

But sympathetic as passengers may be, not many are willing to give up the sense of security and safety that comes from booking rides through a well-known app.

“I get that drivers earn some extra money by cutting out cab aggregators. But as a rider, booking cabs online makes me feel safe. I wouldn’t trade it, even if I empathise with drivers,” says Devyani Sharma, a New Delhi-based advertising professional.

The last effective ‘digital strike’ was in 2021, causing chaos in NCR due to high cancellation rates. At that time, drivers demanded knowledge of the customer’s location and payment mode in advance. The strike succeeded and cab aggregators relented to share destination with the drivers at the time of accepting rides, drivers claim.

However, this time, the digital strike has proven entirely ineffective. Drivers, fatigued from taking to the streets, are losing hope. “I have walked the streets of Delhi without clothes on. It didn’t make any difference,” says one driver.

Across cities, the consistent demand by drivers remains fare regulation, as they claim to be operating cabs at a loss. But customers are reluctant to accept higher rates. “Since Covid, cab fares have shot up. For my everyday commute, I rely on Mumbai’s metered taxis and autos as they’re cheap. I wouldn’t be willing to pay Rs 22 per kilometre,” says Akanksha Dhakrey, a Mumbai-based filmmaker, referring to the fare of a traditional taxi service.

Companies are charging at least a 30 per cent commission on rides and there’s no provision for insurance

-Shaik Saluddin, national secretary, Indian Federation of Transport App-based Workers

Bhatia points out that right now supply is higher than demand. “There are way too many cabs on the streets right now, and not enough rides. The wait time of drivers is also increasing,” she says.

Whether they like it or not, drivers have no choice but to put their keys into the ignition every day. “I have mortgaged my car. I am going to use the money I get from it to pay another loan that I have taken at an interest rate of 25 per cent,” says a cab driver, asking not to be named. “What other jobs are there? There’s nowhere to work.” Fellow drivers murmur their agreement. They’ve put everything into their cars and there’s no way to get off the wheel.

Policy paralysis, but growing political momentum

India’s gig workers, including cab drivers, are stuck in a frustrating purgatory: not quite full-time employees, not quite freelancers. With the central and state governments struggling to fit them into existing policy frameworks, these workers are left vulnerable and without well-defined rights.

The central government’s 2020 Motor Vehicle Aggregators guidelines seemed like a beacon of hope. They outlined specific work hours, capped commission at 20 per cent, and even promised health and term insurance. But these guidelines remain unimplemented, a mirage in the desert of uncertainty.

“Companies are charging at least a 30 per cent commission on rides and there’s no provision for insurance,” Salauddin says. This is a trend Bhatia has explored in her upcoming study, but declined to share details until it is published.

Yet, the winds of change are stirring, with activists championing the cause of gig workers, studies filling in data gaps, and states paving the way for regulations.

The question of gig worker welfare is also getting political. In the assembly elections in Telangana and Rajasthan last month, welfare policies for gig workers featured in the campaign promises of some parties. Salauddin walked with Rahul Gandhi for 15 minutes during the Hyderabad leg of the Bharat Jodo Yatra in November 2022.

Rajasthan is so far the only state with a law regulating gig work, but the newly formed Congress government in Telangana has announced its intention to follow suit. Bhatia, who has been involved in consultations with the Telangana government, calls Rajasthan’s law a “pioneering” legislation even at the international level.

Before this, Karnataka was the first state to introduce guidelines for regulating cab aggregator companies in 2016 called the Karnataka On-Demand Transport Technology Aggregators Rules. In 2022, the West Bengal government notified the On-Demand Transportation Technologies Aggregators (ODTTA) guidelines. While both establish licensing procedures and KYC requirements for drivers, they don’t account for fare regulation and grievance redressal mechanisms—areas addressed by Rajasthan’s law.

Similarly, the Delhi government’s proposed cab aggregator policy, currently awaiting ratification, prioritises passenger safety, but overlooks drivers’ rights.

Cab drivers point out that while elaborate KYC processes aim to protect passengers, it’s a one-way street — all laws and guidelines remain silent on the issue of drivers’ safety.

After they share their experiences and console each other, the drivers vent some spleen, clicking photographs with hard-hitting placards. One reads: “Unemployment made me a driver. The policies of Ola, Uber and the government made me a beggar.”

‘We have no clue who sits in our cabs’

A smattering of high-profile crimes involving cab drivers has heightened concerns among customers about safety. Delhi’s Devyani Sharma ensures she shares her ride details with a family member or friend, especially when travelling late at night. She’s anxious about being in a cab with a total stranger. “As a woman in the city, of course I fear for my safety. People have been raped in Uber and Ola,” she says.

What Sharma may not realise, however, is that drivers are also anxious and have their own safety net. They often share live locations on WhatsApp groups, tracking each other during trips.

“We keep a check on our colleagues. If we know someone is taking a long-distance trip, and his location is not along the route he was supposed to follow, or if the driver doesn’t respond, then all cabs in the vicinity start following his location to ensure safety,” explains 42-year-old Dhara Vallabh, a driver based in Delhi-NCR.

Vallabh says he recently ferried someone called ‘Dony’. Intrigued by the name, he asked the passenger about it. “He told me Dony was the name of his dog. His real name was Amit,” Vallabh says with a tinge of frustration. He shows a screenshot of another ride where the name was just a long number.

Drivers are now demanding a basic KYC completion for all customers who use ride-hailing applications.

“We have no clue who sits in our cabs. It could be a thief, terrorist, or traitor. We don’t know, neither do the companies. It’s dangerous and should be rectified at the earliest,” Vallabh says.

While existing policies ensure thorough vetting of Ola and Uber drivers, customer KYCs are missing from these platforms. According to the central guidelines, drivers have to get a character certificate from the police, a health certificate, show a Jan Dhan Yojana Bank account, and go through other verification steps—but customers get a free pass.

Drivers are fed up with the disparity. They too have read harrowing news accounts and heard scary stories, like that of 20-year-old Raju Kumar who was shot in the leg by three men he was ferrying from Delhi to Rishikesh.

Raju says the men stole his wallet, mobile phones, and other belongings, before throwing him in a ditch near Saharanpur in Uttar Pradesh. With his car gone, Raju is barely able to survive. But he alleges he keeps getting calls from Uber. Not to check on his well-being, but to demand money. “I had informed Uber via phone call about the incident. They didn’t help me, or even close the ride. Even now I have a negative balance of Rs 3,000,” he claims.

Driver WhatsApp groups buzz with shared anxieties and words of succour, and every month around 150 cabbies meet at a dusty hall in Sector 20 of Rohini in Delhi. It’s part-therapy, part-catharsis, and part-mobilisation.

Also Read: Blinkit deliverymen would rather work for Uber-Ola, run YouTube channels. Dignity comes first

‘Bina chaku, churi ke chori …’

The scattered nature of gig work makes it difficult for workers to band together, as does their amorphous employment status. “Unionising in gig work, where workers are not geographically concentrated in one area, is very difficult. So is brokering dialogue with companies who refuse to talk to us, saying we’re not their full-time employees,” Salauddin adds.

But as they wait for tangible change, many drivers are finding sanctuary in self-help groups where shared experiences lighten the load.

Dinesh Kumar, a driver for cab aggregators since 2015, says he feels crushed by the stress of maintaining his rickety WagonR, paying school fees, and dealing with scornful customers.

“I don’t even have money to buy a set of clothes,” Kumar says, glancing down at his torn T-shirt. “Some customers taunt me for the way I look and dress. Some do try to have a conversation and understand my predicament, but others simply make faces.”

When he was younger, Kumar participated in impassioned protests for driver rights. “I walked to the central secretariat in my underwear. It’s not like I haven’t fought for my rights. But it has been of no consequence,” he says. Now, Kumar speaks of drivers collapsing from exhaustion at airport gates and men driven to despair by debt. “Many more of us will be gone if the government doesn’t step in and help,” he says.

But talking to others going through the same ordeal helps. Driver WhatsApp groups buzz with shared anxieties and words of succour, and every month around 150 cabbies meet at a dusty hall in Sector 20 of Rohini in Delhi. It’s part-therapy, part-catharsis, and part-mobilisation.

After they share their experiences and console each other, the drivers vent some spleen, clicking photographs with hard-hitting placards. One reads: “Unemployment made me a driver. The policies of Ola, Uber and the government made me a beggar.”

They also discuss their social media strategies, putting their heads together to make infographics for platforms like X and tagging politicians and influencers that they think might be of help.

“Till now, nobody has responded. But someday they will,” Arun Paswan says.

Leaning against his 2015 Accent, Jagveer Singh says he still loves the car, his Lakshmi in waiting, but not those who drive the controls. “Bina chaku, churi ke chori seekhni ho toh cab companies se seekhna (To learn theft without a knife or dagger, learn from cab companies),” he says.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)