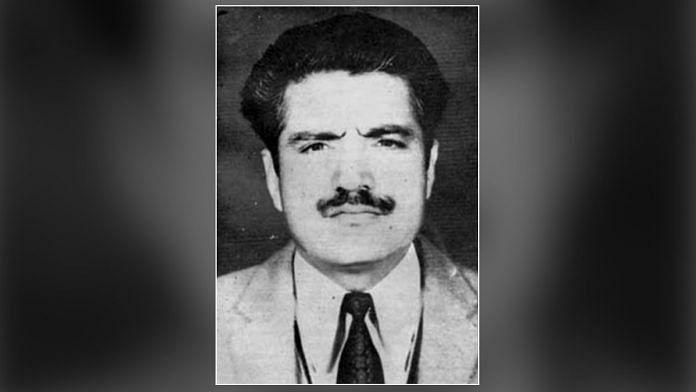

New Delhi: In the wee hours of 11 February 1984, the Indira Gandhi government bypassed long-standing judicial norms to carry out the hanging of Kashmiri separatist Maqbool Bhat at the Tihar Jail in the national capital. The authorities not just refused to hand over his body to his family, he was unceremoniously buried within the jail premises itself.

Bhat was given the death sentence by the Supreme Court but had been abruptly executed to assuage public anger over the abduction and killing of Indian diplomat Ravindra Mahatre in the UK by an alleged affiliate of Bhat’s now-banned terrorist group, Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF).

Thirty-six years later, many in the Valley consider Bhat as ‘Shaheed-e-Kashmir’ — the first ‘martyr’ of the Kashmiri separatist cause.

While his vision of a united and independent Kashmir — including Gilgit-Baltistan in Pakistan and Pakistan-occupied Kashmir — lies in stark contrast with the demands of separatists today, the reason behind Bhat’s larger-than-life presence in the Kashmiri consciousness goes beyond that vision and “martyrdom”.

Working towards his cause, Bhat once managed to crossover the Line of Control (LoC) in the late 1950s, fought elections in Pakistan, founded separatist groups there, then returned to India and eventually escaped from a Srinagar jail back into Pakistan. There he masterminded a hijacking of an Indian plane, questioned the Pakistani judicial establishment after being convicted, and finally crossed back into Kashmir before getting arrested for a last time.

During his lifetime, he propagated the cause of Kashmiri assertion, but some analysts argue he was hardly a known face then and became “Maqbool” only after he was hanged. Others go so far as to argue that without having realised, separatists like Bhat became pawns in the political games which the Abdullahs and Muftis — prominent political families in the erstwhile state — played with Delhi.

“Post 1953, the Abdullahs & Muftis, depending upon their own convenience and opportunism… have alternated between opposing and appropriating the radical/separatist JKLF-Jamaat line and their so-called mainstream ideology,” Javed Iqbal Shah, a political analyst based in Srinagar and New Delhi, told ThePrint.

“A decadent set of vested interest in the police & administration have become its supporting executing arm. This nefarious game continues in cycles till date,” said Shah.

However, a 1984 India Today cover story on Bhat said, “Butt believed in terrorism as the only means to “free” his native Jammu & Kashmir.” It added that during Bhat’s first arrest in 1966, the police “recovered from him a “declaration of war” on India, drafted by him in rousing but stilted English prose”.

In this Past Forward, ThePrint looks at the life of Bhat, who became the leader of the first generation of Kashmiri separatists.

Also read: ‘Appalling condition’ for media — Kashmir journalists ask govt to stop muzzling free speech

How Bhat’s radical ideas came about

Born to a peasant family in Jammu and Kashmir’s Trehgam village in 1938, Maqbool Bhat grew up under a feudal rule, with the Dogra dynasty still controlling the region. According to a report in J&K’s Wande, two events seem to have stirred the political consciousness of a young Bhat.

In 1945-46, the Jagirdar (feudal lord) ordered a raid on his village as it failed to pay up due to a poor harvest. The villagers pleaded with the Jagirdar to reconsider his decision, but when that failed, all the children of the village were asked to lie down in front of the Jagirdar’s car. According to Wande, Bhat was one of those children who eventually led the Jagirdar to overturn his decision.

Bhat’s political consciousness evolved during the 1947-48 India-Pakistan war, but more specifically the Kashmiri resistance against Pakistani invasion in the aftermath of the war.

Beyond these events, the broader political context between Srinagar and New Delhi proved to be a detrimental factor in shaping Bhat’s political ideas.

By 1953, the Sheikh Abdullah-Jawaharlal Nehru pact had fallen apart, and the former had been arrested for conspiring against the Indian state. The growing political discord between Srinagar and Delhi went on to differentiate Bhat’s notion of Kashmiri independence from that of post-1980s separatists.

In the aftermath of Abdullah’s arrest, Maqbool’s earlier moves were probably birthed more by “Kashmir’s sudden trust deficit versus Delhi and an attempt at a reassertion of Kashmiri identity & sub-nationalism than a desire to join Pakistan per se”, said Shah.

Bhat received his religious education at home. Though his politics was devoid of religious nationalism, he continued to ardently practice Islam until his death.

Throughout his early years, Bhat’s revolutionary streak was easy to discern. Along with his teen comrades, he tried to cross over the LoC into the Pakistan-occupied Kashmir (PoK) on four occasions, and failed on each occasion, said the Wande report.

“Maqbool used to make them (locals) all sit in a line there. He had a small blackboard on which he used to draw Kashmir and explain how we were all slaves. Mansoor and I, we were small children then, but we used to watch him,” Abdul Ahmed Shah, a local from Trehgam, told Rediff in a 2001 interview.

By 1957, Abdullah had been released and Bhat, who was completing his B.A., was heading the student wing of an Indian separatist group, Plebiscite Front (PF). Abdullah’s release led to wide-scale protests and a subsequent crackdown on separatist elements including the PF student wing. On 29 April 1958, Abdullah was rearrested and Bhat went underground to escape arrest.

Soon after, along with his uncle Aziz Bhat, Bhat crossed over to Pakistan.

Also read: Padma awardee Muzaffar Baig, ‘Delhi pointman’ in J&K with links to Abdullahs, Muftis & Lone

Disillusionment with Pakistan and beginning of armed struggle

After some years in the wilderness, Maqbool Bhat made it to Peshawar in Pakistan. He enrolled in the Peshawar University to study Urdu Literature, said Wande.

After he moved, Bhat tried his hand at journalism, politics, and political separatism. But each of those avenues failed to help him achieve his vision of a secular autonomous Kashmir. Disillusioned and inspired by armed resistance in Algeria, Palestine, and Vietnam, Bhat finally decided to pick up the pen.

“Maqbool was still feeling restless, thoughts of what was happening back home wouldn’t leave him alone. He joined a local newspaper ‘Anjam’ to earn his living and write his thoughts,” noted Wande.

As a journalist, Bhat started his own magazine, Khyber Weekly, but had to shut it down soon due to lack of funds.

In 1961, Bhat married Raja Begum and had two sons, Javed and Showkat. Though Raja fell ill and passed away, and Bhat later married Zakira Begum — they had a daughter Lubna.

Bhat also entered politics in 1961. In Pakistan’s Basic Democracy elections of 1961, he won the Kashmiri Diaspora seat from Peshawar. During the 1962-63 Swaran Singh and Zulfikar Ali Bhutto talks, Bhat’s disillusionment with the Pakistani political and bureaucratic class began to set in.

In an interview, Bhat once said the Pakistani establishment neither knew nor cared about the Kashmiri cause. This phase drew him away from mainstream politics and instilled a belief that if independence was to be achieved, Kashmiris would have to get it themselves.

“Study any revolution and you’ll learn that it’s the oppressed themselves who should be at the forefront and unless they don’t stand up and fight nothing would happen,” Bhat reportedly remarked in the interview.

On 25 April 1965, Bhat and his compatriots founded the Jammu Kashmir Plebiscite Front (JKPF) in PoK. He was elected as its public secretary. JKPF was the first pro-Kashmir political organisation of any significance in PoK, and most pro-independence groups emerged out of it.

But Bhat soon realised the limitations of political separatism. Along with his comrade Amanullah Khan, he decided to launch an armed struggle through the formation of Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front.

“All forms of struggle including armed struggle to enable the people of Jammu Kashmir State to determine the future of the State as the sole owners of their motherland” was the JKLF’s aim.

In 1966, Bhat crossed back to J&K and started JKLF’s operations.

Also read: Right-wing exaggerates number of Kashmiri Pandits killed. Militants targeted Muslims more

Prison break, hijacking and final fallout with Pakistani establishment

While Maqbool Bhat and his fellow JKLF members started joining the ranks of militants, their activities were hit soon. As violence grew, the security forces cracked down on the group.

In 1966, Bhat was arrested and accused of murdering a CID official. As the case concluded two years later, Bhat was charged under the Enemy Act of 1943 and sentenced to death. He was moved to the Bagh-e-Mehtab interrogation facility in Srinagar. On 8 December 1968, Bhat and his comrades Amir Ahmed and Ghulam Yasin dug a 38-foot tunnel and escaped.

“Our escape was no coincidence, we didn’t just see an opportunity and took it. Right from the time they put the shackles on me, I was thinking of ways to escape,” claimed Bhat during a 1972 interview.

The separatist then travelled for hundreds of kilometres on feet and managed to cross back into Pakistan-occupied Kashmir a second time.

After a brief detention, Bhat found himself back in the thick of things in Pakistan. He was chosen as the chairman of the Plebiscite Front (a Pakistani party, different from the one in India) and decided to restart JLKF’s operations.

Over the next few years, a series of events put Bhat on the radar of the Pakistani state too.

In 1970, the Pakistan government proposed the Azad Kashmir Act, whereby PoK would come under complete control of the Ministry of Kashmir Affairs and the Chief Secretary. Moreover, Gilgit Baltistan’s autonomy was further quashed, and it was to be controlled by an establishment’s political agent.

The Azad Kashmir Act effectively ended Bhat’s hopes of an autonomous united Kashmir, and was staunchly opposed by the (Pakistani) Plebiscite Front. The group carried out protests all over Pakistan, including in PoK, but was met with an iron-fist crackdown by the government.

By 1971, Bhat was elected as the JKLF leader.

Looking to internationalise the Kashmiri cause, he masterminded the hijacking of Indian Airlines flight 101 ‘Ganga’ to Lahore. The hijacked ‘Ganga’ aircraft was brought to Lahore, and though the passengers were sent back to India, the plane itself was blown up by the hijackers.

“Hashim (Qureshi — one of the two hijackers) told me that the 1971 hijacking of the Indian Airlines plane ‘Ganga’ was Maqbool Butt’s idea,” wrote A.S. Dulat, former Research & Analysis Wing chief, in his book, Kashmir: The Vajpayee Years.

This hijacking led to New Delhi enforcing a ban of Pakistani flights in the Indian airspace, and had a direct consequence on the Indo-Pakistan war of 1971. The Pakistani military’s efforts were greatly restricted, as they could not fly their troops to West Pakistan. The war ended with the dismemberment of Pakistan and the creation of Bangladesh.

Kashmiri analysts told ThePrint that the hijacking was initially supported by the Pakistani political class, which turned Bhat into a hero overnight.

However, his rise amid the Pakistani establishment met a preordained fate. A judicial committee was set up, and it eventually concluded that JKLF had a role in hijacking. As its leader, Bhat was charged under the Public Enemy Act.

This meant Bhat had been charged with the Enemy Act in both India and Pakistan.

Several analysts told ThePrint that the Pakistani crackdown needs to be seen in a particular context. By the time the hijacking took place, Bhat’s idea of a secular united Kashmir had started to gain currency, and so, a crackdown on his activities became a necessity.

Bhat was eventually acquitted by a Pakistani court, but the massive government crackdown on JKLF had left the group in complete disarray.

Also read: ‘He was shot at outside his shop’ — Family denies man hurt in J&K gunbattle is a militant

Maqbool Bhat — an idealist, a pawn or just a separatist?

A lack of well-researched literature on Bhat means it’s difficult to assess his life in a larger context of the Jammu and Kashmir politics.

Chindu Sreedharan, an academic and former journalist who has interviewed several Kashmiri militants including Hashim Qureshi, said, “There has been no systematic study on Maqbool Bhat. All we know about him essentially comes from anecdotes.”

In view of this, the transcript of Bhat’s defence at the Pakistani court during the hijacking trial is of vital significance. His dislike for Pakistan was apparent in his words, when he used the Quran to criticise the hypocritical character of Islamabad. His idealist revolutionary ideas were also evident in his speech.

“… history also is witness to the fact that in this battle between truth and falsehood, it is we, the oppressed, who have always emerged victorious. It is we, the people, who demolish these edifices of oppression,” he told the court.

His stark indictment of the Pakistani judicial establishment symbolised his ‘revolution’.

“If the evolution of civilization, democracy, and freedom was to be prevented by the existing judicial or administrative system no revolution would have taken place from the beginning of history,” Bhat said.

“According to Maqbool, the international community would not support Kashmir’s accession to Pakistan, but it would support azaadi — on both sides,” Dulat wrote in his book.

Comparing Bhat with Kashmiri militants post his execution, Noor Ahmad Baba, professor, Central University of Kashmir said, “Bhat was a visionary. The first generation of militants who crossed over, did it because they were disillusioned and were idealists. In comparison, the post-1987 militants were also affected by circumstances in the valley.”

But Bhat’s popularity and role in J&K’s separatist cause is far from unchallenged.

“He was hardly a popular figure in Kashmir during his lifetime. He spent most of his time in Pakistan. It is only after his hanging Maqbool managed to capture the Kashmiri imagination,” said Baba. “He became the face of Kashmiri resistance after that.”

Bhat’s hanging

After being acquitted by the Pakistani court, Bhat yet again decided to re-establish his separatist group JKLF. Against the advice of many of his friends and comrades, Bhat moved back into Jammu and Kashmir in 1976. Just a few weeks after he crossed over, he was captured by Indian forces.

In 1978, the Supreme Court of India restored his death sentence and he was moved to Tihar jail in New Delhi.

According to Sunil Gupta, former public relations officer of Tihar, while in jail, Bhat spent most of his time reading and teaching fellow prison-mates and jail officials about Kashmiri politics, and praying. Gupta told ThePrint how he used to visit Bhat from time to time, and the latter would help him improve his English.

However, after the assassination of Indian diplomat Mahatre by an alleged JKLF affiliate on 3 February 1984, the Indira Gandhi government quickly moved to carry out the execution of Bhat in a bid to assuage public anger.

While Bhat was hanged eight days later, two aspects of his execution have raised eyebrows over the years.

First, according to Bhat’s legal team at the time, the Jammu and Kashmir High Court’s document that ordered the execution of Bhat had been left unsigned. This became a point of contention in the Supreme Court, but it eventually cleared the move.

Second, his sympathisers continue to argue that a case against Bhat was still pending at court, and it is legally murky to execute someone while they are still being tried.

In an interview to Rediff, Hashim Qureshi claimed that Amanullah Khan — who had by then founded JKLF’s branch in London — was behind the kidnapping and killing of Mahatre, and not Bhat.

According to Qureshi, killing the diplomat was akin to signing Bhat’s death warrant.

Also read: MHA gets bigger role in picking J&K Police days after DSP’s arrest for ‘aiding militants’

Many in india want to dump all muslims into kashmir and hand it back to pakistan.