Why PastForward

Because what happened in the past matters for us going forward. Because many big stories never go away. They endure or fester through generations. Many have lessons for now and the future. Some others are just so interesting and important, you must bring them back to readers, especially the young, post-Google generation.

In PastForward ThePrint’s reporters will investigate key events of the past, talk to participants, look at archives and draw lessons and parallels with the present.

The series opener takes you 50 years back to Nathu La in Sikkim, where India and China were involved in their last violent clash in the fall of 1967. Indian Army and military historians, including many in the Western world, think the Chinese suffered much heavier losses. The Indian Army vindicated itself after the humiliation of 1962.

Important fact: the place isn’t far from Doklam, the zone of contention now.

Deputy Editor Manu Pubby worked with reporters Vandana Menon and Nayanika Chatterjee to piece together this brilliant story, the first in the PastForward series.

Shekhar Gupta

Editor-in-Chief

***

On 13 April 1984, India launched Operation Meghdoot to wrest control of Siachen Glacier and gain a strategic upper hand on Pakistan.

New Delhi: It is almost 15 years back that the last bullet was fired on Siachen Glacier, the world’s highest battlefield where more Indian and Pakistani soldiers are killed by the inhospitable weather and terrain than gun fire.

Relations between India and Pakistan since haven’t been as stable though. Heavy machine gun fire and even artillery duels have returned to shatter the years of quiet on the frontier in Jammu and Kashmir. Peace talks have been suspended after the two countries seemed to be making unprecedented progress during the Manmohan-Musharraf years and appeared close to resolving decades of bitter hostilities – including a possible demilitarisation of Siachen.

Although there is little hope of any rapprochement in the near future as both neighbours are due to hold general elections in the next one year, Siachen remains a glacier of calm. A calm that is largely attributed to the fact that the Indian Army is in control of the glacier – thanks to the fact that it holds the better and higher positions, is better equipped and has superiority in numbers.

But the position of strength did not come easy. As India marks the 33rd anniversary of the daring military operation that wrested control of Siachen, ThePrint looks back at one of the most audacious sagas in the history of the Indian Army.

The Cold Facts

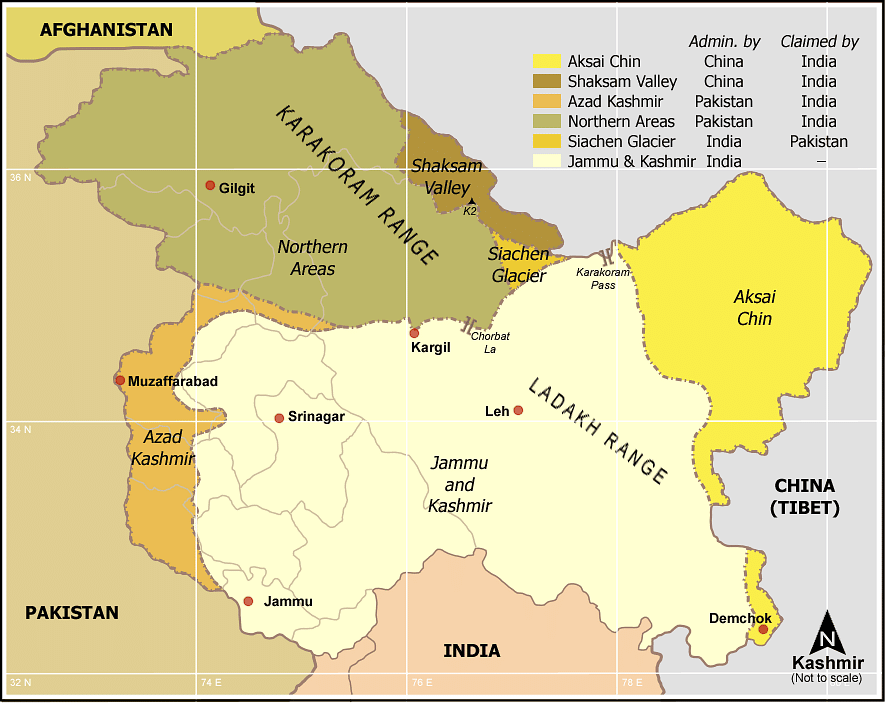

Siachen is 20,000 ft above sea level, in the icy Himalayas where temperatures are known to plunge up to 50 degrees below 0°C. It is located to the north of Ladakh, stretches about 2,600 sq km and was thrust into the limelight in the 1970s.

India controls the 70-km-long stretch of glacier, and reportedly spends about Rs 3 crore-Rs 5 crore on it daily. The amount goes towards the upkeep and health of the seven battalions stationed there. This adds up to about Rs 1,500 crore a year.

India and Pakistan have both lost about 1,000 soldiers each since 1984, with just about a fifth of India’s casualties attributed to gun fire until the 2003 ceasefire.

For a long time, both India and Pakistan assumed Siachen was their territory. Neither the Karachi Agreement of July 1949 nor the Simla Convention of 1972 offered clarity on the status of inhabitable areas north of the Line of Control’s northernmost point, NJ 9842.

The CIA reported in its ‘Near East and South Asia Review 1985’, “Given the area’s remoteness at the time, this imprecision presumably was not considered a problem. After the 1971 war, the ceasefire line was adjusted to reflect actual control when the fighting was halted. Since the war was fought in December, neither side was likely to have had sufficient forces on the glacier to require a more exact drawing of the ceasefire line.”

In the late 1970s, both countries embarked upon mountaineering expeditions in the region. First, Pakistan allowed many such expeditions. It was noted in the aforementioned CIA report, “Islamabad established military observation outposts on the glacier and began to sponsor foreign mountaineering expeditions to the region.” These tactics eventually “secured international acceptance of Pakistani control over the area”.

In 1978, India also undertook some, with the expedition to Teram Kangri, led by Colonel Narinder ‘Bull’ Kumar, being among the notable ones.

The Indian Air Force’s (IAF’s) participation yielded an interesting anecdote. In 1978, when asked to drop off some fresh food for an Indian expedition at Siachen, Air Vice Marshal M. Bahadur (Retd) said the personnel decided they would also pick up some letters from those at the glacier, and deliver them to the recipients. However, when IAF personnel reached the glacier, they realised the men at Siachen didn’t have any paper to write letters on. The IAF pulled off its first landing at Siachen on 6 August 1978.

Tensions erupted after India realised that Pakistan and the US had begun to issue maps showing the region as Pakistani territory.

Lt. Gen. Sanjay Kulkarni, the man who planted the first Indian flag in Siachen and spearheaded ‘Operation Meghdoot’, through which India wrested control of the glacier, called it an act of “cartographic aggression”.

In 1984, Pakistan allowed a Japanese expedition to scale Rimo 1, which lies in Siachen’s vicinity. This was discovered when, on one of the Indian expeditions, Lt. Gen. Kulkarni noticed wrappers with Japanese text littered on the trail near Bilafond La, a pass in the Saltoro range that serves as a gateway to Siachen.

Rimo I overlooks Aksai Chin, a territory at the centre of a dispute between India and China. Claimed by India, Aksai Chin is occupied by China. The expedition led the Indian government to suspect that Pakistan could be scouting the possibility of a trade route with China through the Karakoram range, of which Rimo I is a part.

The glacier lies between the main Karakoram range and the Saltoro Ridge. From north to south, the major passes on the Saltoro Ridge are Sia La, Bilafond La, and Gyong La.

As the CIA pointed out in a report, “What little strategic value the glacier area has lies in its passes, which though remote and not easily traversed, reach through the Karakoram Range into China. To Pakistan, these are potential support routes from an important ally. The Indians, therefore, consider denying Pakistani access to these passes to be a key strategic goal.”

Siachen thus took centre stage in the India-Pakistan saga.

Operation Meghdoot

Operation Meghdoot began with Bilafond La.

Former Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf, who was just a Brigadier at the time, wrote in his memoirs, ‘In The Line of Fire’, that the Indian troops “pre-empted” Pakistan when it came to Siachen — clearly indicating that the country did have plans to occupy the glacier entirely. In fact, Operation Meghdoot took place just days before Pakistan had scheduled its ‘Operation Ababeel’.

On 13 April 1984, the first Indian platoon landed near Bilafond La. The date was a specific choice: It was Baisakhi, and the Indian Army thought it was an ideal day to take Siachen. According to Lt. Gen. Kulkarni, the commander of the first platoon to land on Siachen, all the winter equipment and clothing arrived at the base camp just the evening before.

Within the first hour of landing, the radio operator fell ill with high altitude pulmonary oedema or HAPO, a condition in which water accumulates in the lungs at high altitudes, and had to be evacuated.

The 29 soldiers who had landed there were ordered to maintain radio silence so that their movement would not be detected by anyone else. The Indian soldiers were to occupy both Bilafond La and Sia La — but the weather rapidly worsened, and the occupation of Sia La was called off until it cleared up.

“The visibility was virtually zero, winds blowing very fast, and temperatures touched down to -30°C,” said Lt. Gen. Kulkarni.

Over the next two days, a soldier died because of HAPO. “We were now in a dilemma as to what to do,” Kulkarni said. “The orders were very clear: ‘Don’t open the radio sets’. But we had no other option than to open the radio set and inform them that one of our boys is no more…and needs to be pulled back.”

Within no time, a Pakistani chopper arrived at Bilafond La.

However, the Indian soldiers moved and occupied Bilafond La, and when the weather cleared up on 17 April, they claimed Sia La as well. Another battalion moved to occupy Gyong La.

“While this was going on, the Pakistanis discovered the Indians had occupied the passes, and so the race for Saltoro Ridge started,” said Lt. Gen. Kulkarni.

The first shot fired on Bilafond La was in May, and the first attack on 23 June, which India thwarted, bringing a successful conclusion to Operation Meghdoot.

After Operation Meghdoot

The situation at Siachen has been at an impasse since. Both India and Pakistan maintain a permanent military presence on the glacier, but haven’t had a serious confrontation.

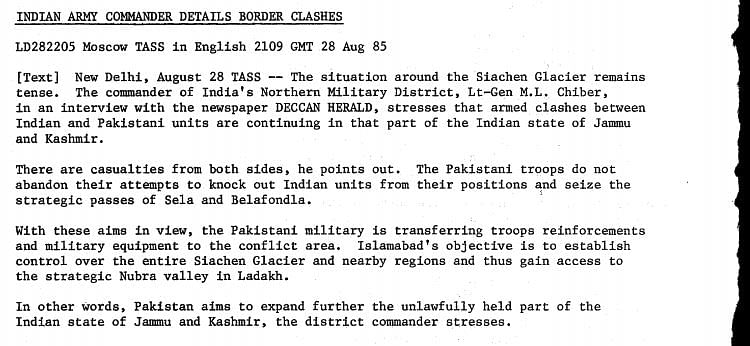

CIA reports from the 1980s reflect tension that never reached a boiling point.

This CIA report from August 1985 pointed out that Pakistan was aiming to “expand further the unlawfully held part” of the state of Jammu and Kashmir.

The CIA’s monthly warning report for March 1988 said that Pakistan “may want to recover” parts of the glacier.

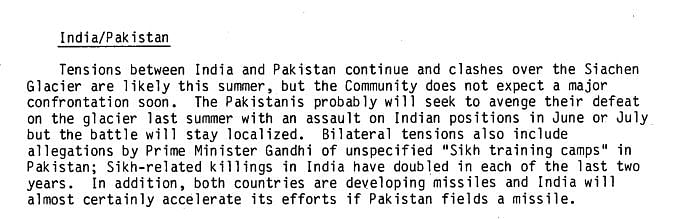

Another warning report, from May 1988, said clashes were likely, but a major confrontation was not expected. The battle would stay “localised”, it said.

“Neither side can support military activity on the glacier,” the CIA’s Near East and South Asia Report for 1985 said. “Both countries will, therefore, be likely to pursue military contact on the Siachen glacier within the strict limits of geography and climate.”

‘Menacingly beautiful’

The glacier is a source of intrigue, and its harsh conditions haven’t undermined its beauty for soldiers, according to the Lt. Gen. Kulkarni and AVM Bahadur.

“It’s actually menacingly beautiful,” said AVM Bahadur.

“It’s a beautiful place to be in, irrespective of the sub-zero temperatures,” said Lt. Gen. Kulkarni. “A lot of lives have been lost because of HAPO, lots of frostbite and chilblain cases where people have lost their limbs because of the blizzardous weather,” he added.

“Notwithstanding these kinds of hardships, if…you ask anybody in the Indian Army, it is their desire to one day serve on Siachen,” he said. “The acid test for a soldier is to have served in Siachen.”

Talking about the camaraderie between IAF and Army pilots and the jawans stationed at the glacier, AVM Bahadur said it had to be seen to be believed.

According to the AVM, there is a “world of a difference” between the living conditions in Siachen in the 1980s and now. Soldiers are stationed there for 90 days, and have access to better food, entertainment, and “first-class” equipment.

“The soldier on the glacier is very well-equipped. Food is in plenty,” he added.

“Comfort levels have gone up,” Lt. Gen. Kulkarni said. “I would say we are far more comfortable, far more prepared, and far more acclimatised now than others,” he said, referring to Pakistani army personnel.

Relevance of Siachen today

Operation Meghdoot was a major victory for the Indian military but some critics argue that there is little else that is significant about it.

In 1985, a CIA report noted as much. “Combat on the glacier is infrequent and low in intensity. The fighting involves mostly small arms and indirect weapons fire,” the report said.

“Avalanches and cold weather injuries are far more serious threats. Operations are virtually impossible in the winter because of bitter cold and high winds, and they are extremely difficult and dangerous in warmer seasons because of crevassing and avalanches.”

It is not that India and Pakistan are not conscious about this. It is just that given their acrimonious past and continued distrust of each other, neither is willing to take the chance of disengaging from the world’s highest battlefield.

@Nadeem Alam Zubairi: What a sick person you’re Nadeem. You should be ashamed for your last statement – ” Indian losses in terms of money and lives are much greater.” So this is what your humanity.

The article is based from an Indian prospective, if you have an Pakistani prospective article – go ahead & publish them. If India wanted to occupy more space, we might’ve captured Pakistani territory long back. Our tanks reached your cities – you guys still have some of the tanks India lost when entering them, your then PM had to beg UN/USA to intervene to stop India from taking over Pak. And more over our history books don’t spread hatred & lies unlike yours. (your own historians have stated that numerous times, its not my word against yours). We’ve had a shady past but we study it – we don’t ignore it.

All I’ve heard is lies & more lies from your side. Your own media institutions found Kasab to an Pakistani resident but you guys won’t believe it. Then you guys claim you won Kargil war too, which even your own best current friend China doesn’t support.

A bunch of lies this article is. The mere fact that Indian plan of a much much greater occupation of the area by a surprise and uncalled for advent was foiled by totally unprepared and unequipped (for mountain war fare) yet brave Pakistani troops is difficult to digest by India. In this denial phase they are continuing their presence there knowing clearly that initial plans have failed but still ready to waste billions of tax payer money and lives. Go ahead. Indian losses in terms of money and lives are much greater.

Why would you not shown Jammu&Kashmir “claim by Pakistan” on map….?